The idea of a full gathering together of the enormous corpus of photographs taken by William Henry Fox Talbot and his circle is the culmination of more than four decades of researching his holdings worldwide. At present, I know of more than 4500 distinct Talbot images and more than 25,000 surviving negatives and prints. This project is an attempt to make sense of all of that. When I first started visiting Lacock Abbey at the end of the 1970s, the late Bob Lassam, Curator of the Fox Talbot Museum, was wonderfully encouraging about achieving a fuller understanding of Henry Talbot. Like other researchers before me, including Harold White, Eugene Ostroff and H J P Arnold, I found the sheer mass of documentary material that was available simultaneously stimulating and daunting. Fortunately I was able to salvage something from my brief and failed career as an electrical engineer, for in 1965 at the University of Illinois I had used the first transistorized university ‘super computer’, the Illiac II. By 1982, the first model of the IBM-PC had freed me from punch cards and began to allow an organisation of the data that would have been impossible just a generation before.

Talbot’s great-great grandson, the late Anthony Burnett-Brown, very kindly made the deep recesses of Lacock Abbey available to me, and along with his sister Janet was endlessly patient in answering questions. Both travel and access to collections seemed easier then and I was able to build on the tree of Lacock’s collection to add data on Talbot holdings from throughout the world. I introduced my own organisational system, the Schaaf numbers, that allowed me to relate negatives and images in public and private collections worldwide. The cooperation and active support of many curators, librarians and individuals was crucial to building this mass of data.

The database for Talbot’s images developed in parallel with related ones of his correspondence and his notebooks. These were all in DOS and had limitations that are hard to believe today. Every byte counted, so words had to be abbreviated, thoughts truncated, and the direct inclusion of images was impossible. By the late 1990s, at just about the time google was taking root and email was started to replace the fax machine, the web was beginning to grow in usefulness to the humanities. Putting Talbot’s letters online emerged first, in large part because it was text-based rather than image-based. Delivering transcriptions of 10,000 letters posed serious technological challenges at the millennium, but colleagues at the University of Glasgow met the challenge and The Correspondence of William Henry Fox Talbot went live in 2003. However, delivering 25,000 images at the time would have ‘broken the web’ (with more certainty than as a celebrity recently claimed). As late as the year 2000, I still thought the Catalogue Raisonné would be published as a large set of volumes gracing bookshelves. They would have been beautiful and useful, but a web-based catalogue is much more flexible in searching and more readily updated. Today, digital images, vast amounts of storage, sophisticated database and web designs and high speed broadband connections make the technological aspects of the online Catalogue Raisonné feasible. The alliance of the William Talbott Hillman Foundation and the Bodleian Libraries is finally turning that feasibility into a reality.

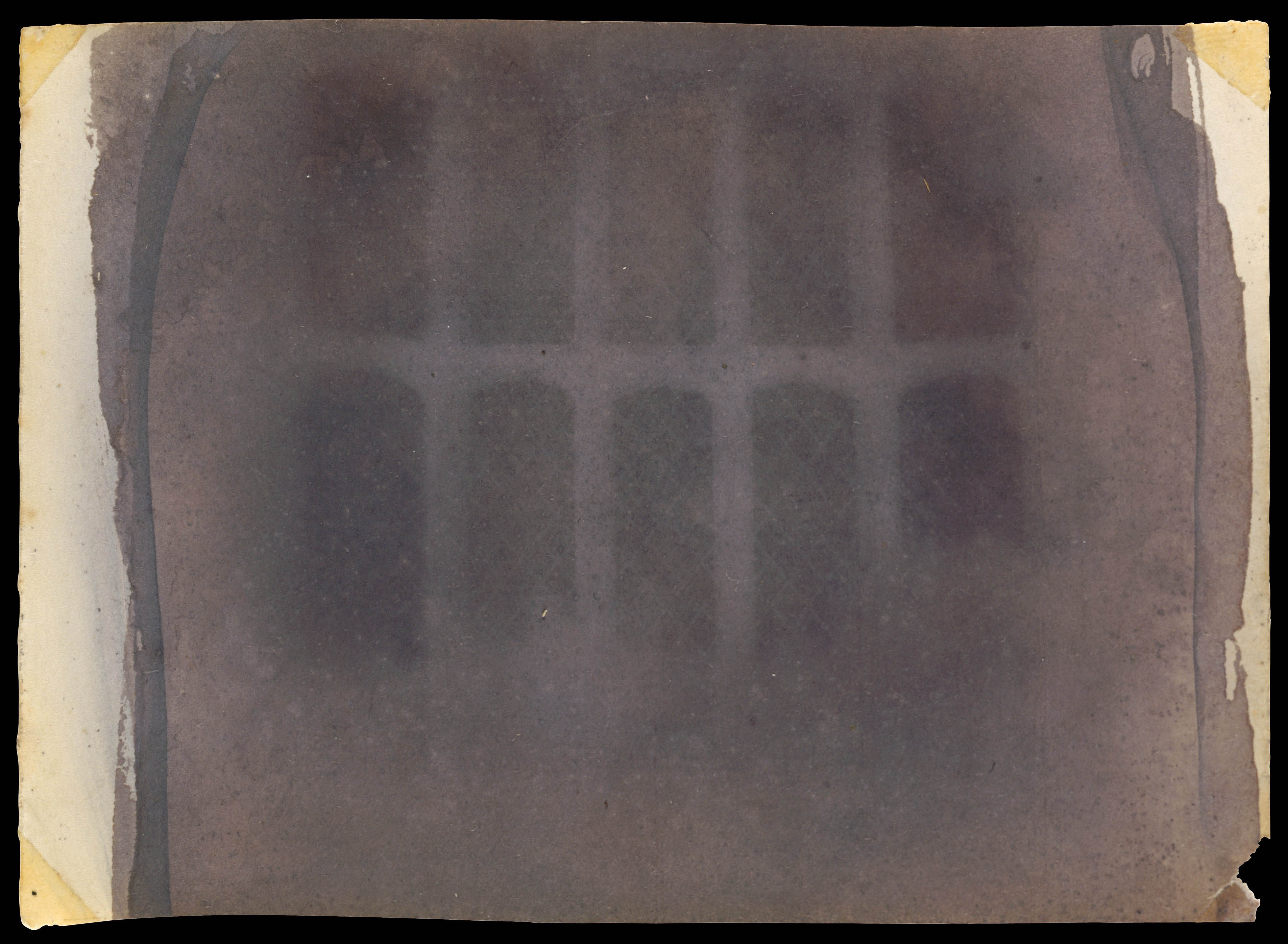

The Illiac II lasted for about a decade before being scrapped. It succumbed to rapidly evolving computing power, an evolution that has continued inexorably to the point where the mobile phone now in your pocket has far more ability than this massive instrument ever possessed. Talbot’s tantalizing view looking out through his window is now approaching two centuries in age. The idea of working with computers still engages me, an idea planted fifty years ago by my first exposure to a thinking machine, and one that has influenced my work in the humanities ever since. But Talbot’s much older photograph remains captivating and even seductive. However long it lasts (and with proper stewardship that should be a very long time), its ability to convey the spirit of an idea – Henry Talbot’s imaginative harnessing of nature – is a fabulous demonstration of the very power of photography itself.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • William Henry Fox Talbot, The Oriel Window, South Gallery, Lacock Abbey, probably 1835, Photogenic drawing negative, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Rubel Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee and Anonymous Gifts, 1997 (1997.382.1), Schaaf 1100. • Illiac II computer, ca. 1963. • A print edition intended at the time as a model for the Catalogue Raisonné is my Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot (Princeton, 2000). • The more than 10,000 transcriptions of letters in the Correspondence of William Henry Fox Talbot project is now hosted at De Montfort University in Leicester.