I am in Pasadena, California right now, not entirely to visit the legendary Rose Bowl Flea Market for the first time, but rather to attend the annual meeting of The Daguerreian Society. It is always a jolly affair (I’m actually a secret agent who has been inserted into the Society to promote the idea of changing their name to The Daguerreian Era Society in order to bring Talbot studies under their impressive umbrella). I took advantage of this ‘leveraged flyout’ to stop by the Getty to have another look at their items from the Henry Bright album, three examples that I last saw fifteen years ago. Readers whose short-term memory has not been totally corrupted by google might recall the perilous journey of The Damned Leaf, discussed in an earlier blog. Today’s ruminations are not about that controversy, instead examining how close analysis of the Brights can possibly inform studies of similar Talbots. Rest assured, no originals were harmed in today’s study – it has all been done by visual analysis.

When I first saw this group of material in 1994, I re-attributed the left two from Nicolaas Henneman to Talbot – the original attribution had been based on an erroneous auction house reading a decade earlier of ‘N’ for the ‘W’ with which some of them are inscribed. For good reasons that still remain persuasive even to me, I attributed the right hand one to Sir John Herschel – I now am beginning to think that Henry Bright himself is an equally strong candidate.

But I digress.

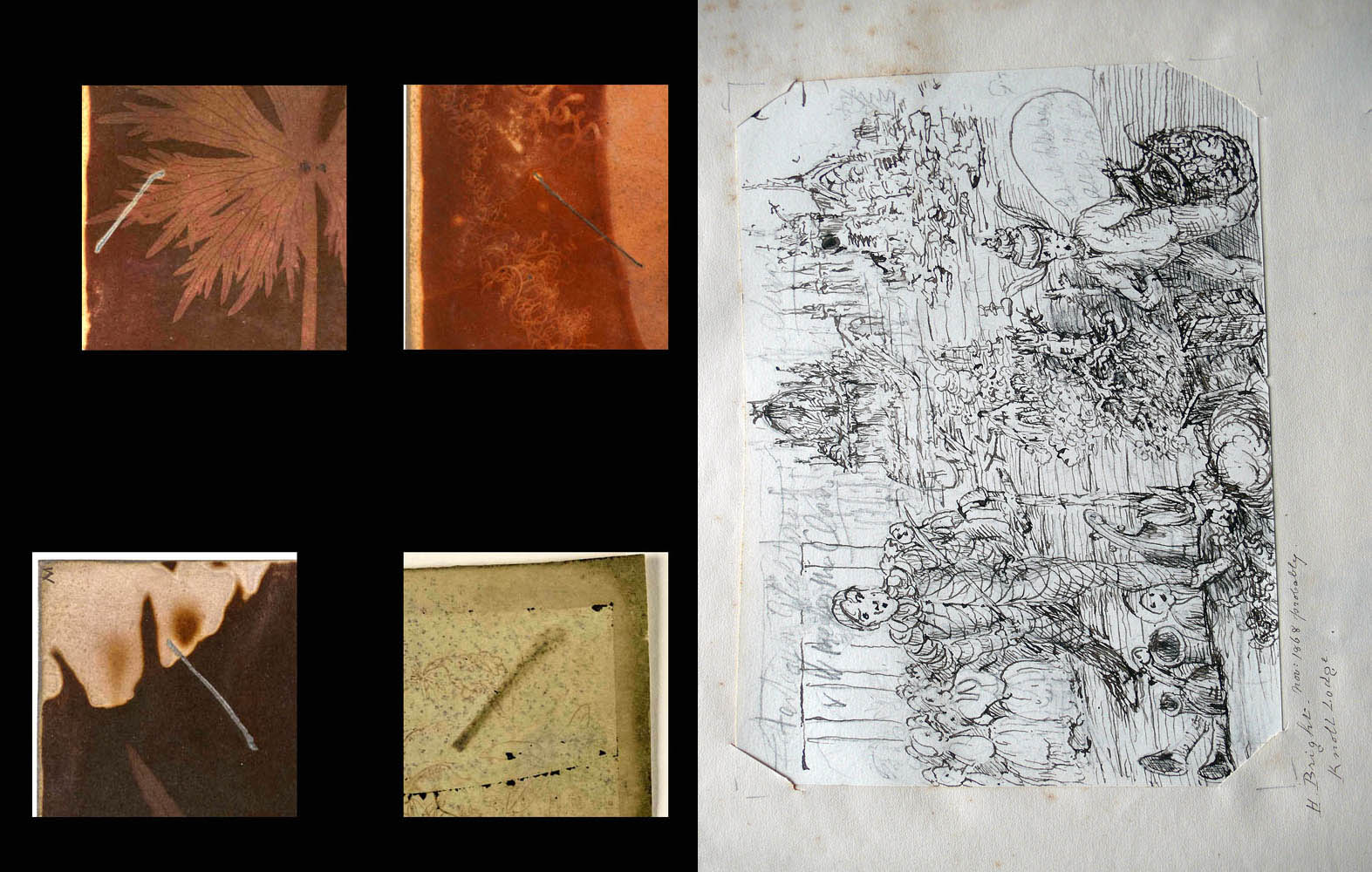

One of the intriguing aspects of the Bright photogenic drawings is the mysterious surface markings on four of the seven. These diagonal lines almost appear to have been defacings done with an angry stroke of a very blunt pencil.

Looking at three Brights together earlier this week, it suddenly hit me. In 1984, Philippe Garner, one of the most studious auctioneers ever to grace the photographic market, included in his catalogue a photograph of the original album page taken before it was cut into seven pieces for individual sale.

Philippe’s intuitive sense that the full album page should be recorded for posterity served to preserve some vital clues. Laying the Brights out on a table (virtually) in the pattern preserved by the catalogue page, the meaning of the diagonals suddenly became apparent to me.

These mystery markings are evidence of a once-adjacent album page. In 1984, the family sent this album to Sothebys in order to sell the watercolours and sketches in it. The album was broken up without any record of its structure or contents, but the memories of everyone involved indicate that it was typical of several albums assembled by Henry Bright that are still within the family’s possession. Most of the larger watercolour and ink drawings were mounted in these albums by tucking the corners under four diagonal slashes, sometimes left loose, sometimes gluing the flaps in from the back.

This was a very common mounting technique seen in diverse 19th century personal albums. Talbot himself used it in several of his personal albums.

The Henry Bright ink drawing on the right is a typical example selected from another of the family’s albums. From this, it seems abundantly clear that the mystery markings correlate with the four slashes in the next page in the album. The middle three on the page escaped this fate. Whether these markings are chemical traces from the line of glue used to hold the next watercolour, or pressure marks from being squeezed together in the album, or collateral damage from the art on the next page being removed by the auction house more than a century later we do not know. One more interesting task for the conservators.

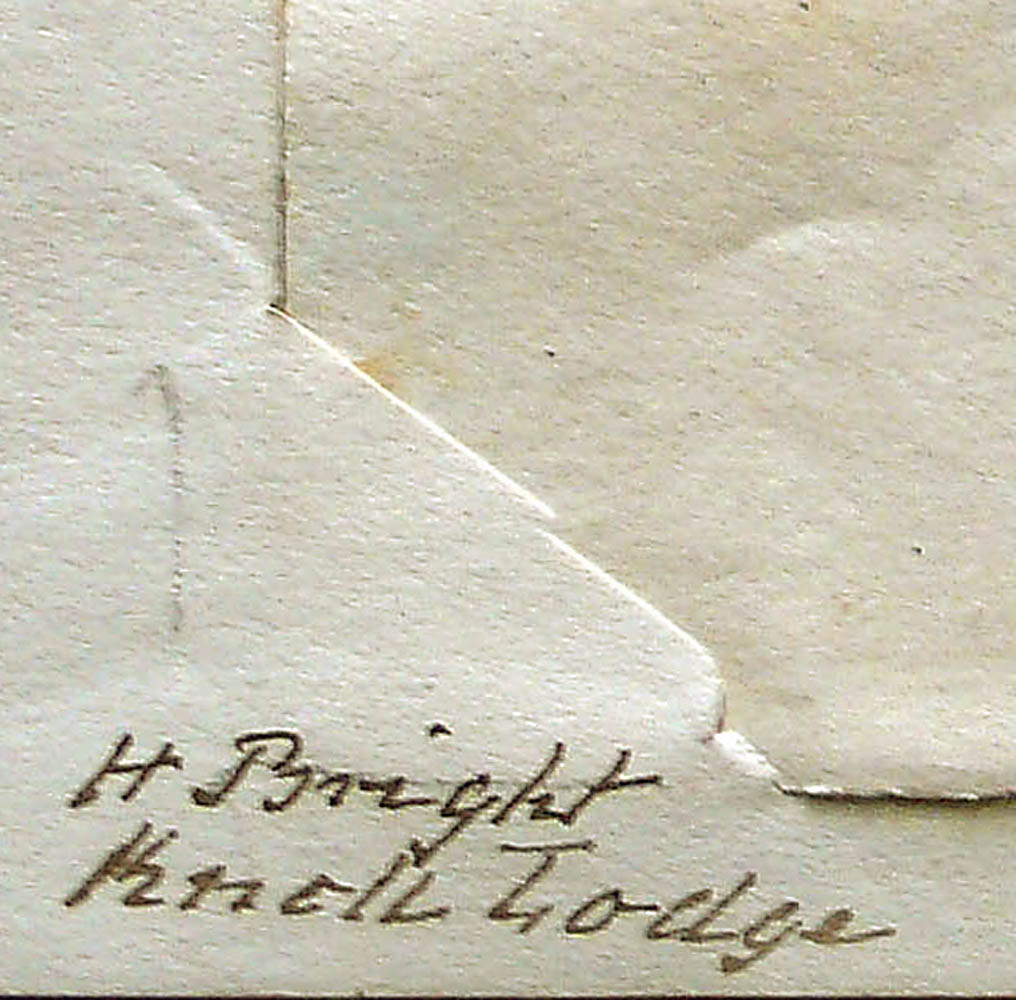

Back in 1994, I had not paid any attention to the small sheets of paper on which the Getty’s two Sarah Anne Bright images were mounted. Seemingly trivial, they are not even noted in the official Getty accession or catalogue records. The third one, the cliché verre, has an extensive caption on verso which probably explains why the album paper was removed sometime after the auction. Given traces penetrating through the album page paper, obviously the glue used by Henry Bright to paste them down was the cause of the severe fading pattern. Some of the Brights are still on the same kind of paper. I am sorry that a snapshot could not be made available in time for this blog, but the paper mount of the upper left one is more complete and shows a definite sunning of the upper edge, confirming its placement in the album. These scraps of paper are the remnants of the original album page.

It was Philippe Garner’s prescient action for his catalogue that made this analysis possible, yet his was a great exception in the usual auction catalogue practise. It is probably only by benign neglect that some of these Brights remain on their scrap of the original album page. How many times in the past have early photographs been removed from their album pages – for promotion of commerce, or in order to tidy up a display, or out of well-intentioned conservation concerns? These scraps have almost invariably been discarded. What clues have we lost? One of the goals of the Talbot Catalogue Raisonné is to encourage and enable the virtual reassembly of this sort of information. Scraps of paper and scraps of documentation can both yield scraps of knowledge. Even the footprint of a slash can fill in a little piece of the grand puzzle.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • In the original album page layout, the top left and bottom two examples formerly belonged to Michael Wilson and are now in the J Paul Getty Museum. The top right was in the Gilman Paper Company Collection, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In the center row, the one on the left of course is ‘The Damned Leaf’ owned by the Qullan Corporation. The other two in the centre row are in two different private collections. It was the stationer’s blindstamp on the small one in the centre that proved to be the key to identifying all of these. Little things matter.

![[Hornbeam Leaf]; William Henry Fox Talbot, English, 1800 - 1877; 1840; Photogenic drawing; Image: 11.6 x 14.9 cm (4 9/16 x 5 7/8 in.), Mount: 14.1 x 17.5 cm (5 9/16 x 6 7/8 in.); 84.XP.927.7](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/foxtalbot/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/11/mark.jpg)