Mixed into the boiling pot of disturbing European news in 1934, Estonian readers of the Postimees newspaper must have been pleasantly surprised to see a story about an Englishwoman and her distinguished and inventive grandfather.

Henry Talbot’s granddaughter, Matilda (1871-1958), ‘Maudie’ to family and friends, led an incredibly varied and productive life and will certainly figure into future blogs. More than eight decades ago she embarked on a mission to make her grandfather’s work better known, creating little pockets of Talbot holdings in places that might not at first be anticipated. One of these was Tartu, the intellectual capitol of Estonia, which I had the privilege of visiting last month.

My title “very far away from England” quotes Matilda’s reaction when she first arrived in Estonia. One of the chapters in her My Life and Lacock Abbey curiously combines “Visits to Estonia – Cookery and Food Exhibition at Lacock Abbey,” hinting at some of the varied complexity of her activities. In the summer of 1934, the Girl Guides held an international conference in England. Active in the organisation, Matilda invited a group to Lacock Abbey. She was particularly taken with the Chief Commissioner of the Estonian Girl Guides, Eleonore Hünerson, the language mistress of the High School of Tartu. They shared music and stories and perhaps the visitor had a chance to examine the massive exhibition of Talbot’s photographs then mounted at Lacock Abbey by Matilda and her brother. That September, responding to the reciprocal invitation, the fearless Maudie found herself the only passenger on the ‘Baltallin’, a small cargo boat destined for Riga. Her train from there arrived in Tartu at four in the morning, but Mrs Hünerson and a daughter were waiting on the platform to welcome her to a strange new land. The visit delighted all and subsequently daughter Helgi made an extended visit to Lacock and Maudie returned to Tartu in 1935 and again in December 1938, departing shortly after Christmas and just ahead of the catastrophic events of 1939. Estonia had some of the highest losses of the war, an estimated 25% of their population. Thus, it is not surprising that the exact time and means by which Matilda’s donation arrived in Tartu is now uncertain. The Nädal Pildis of 14 September 1939 illustrated with “Fox Talbot’s first photographs from the collection that was donated to Tartu University Library on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of photography by an Englishwoman.” This was before Miss Talbot’s arrival, so either she sent them ahead or the Hünerson’s perhaps had received them in advance. The donation was first recorded in the ‘Liber Daticus’ (the university’s gift book) in March 1941, but given wartime conditions it is impossible that they were conveyed then. Many of the surviving academics left Estonia at the end of the war and much history was lost. Indeed, it is something of a miracle that the entire Talbot collection survived the desolation of war and the subsequent occupation by the Soviets.

One of the prints that she sent was a depiction of lace, done by making a photogram directly on a sheet of photogenic drawing paper and then printing that very sharp and detailed negative onto salted paper. Talbot noted a certain irony in that white lace came out looking black this way, for the threads of the lace blocked the sunlight from reaching the sensitive negative paper, leaving a void that would in turn be rendered dark in the print. This example is one of my favourites because of its folds and creases, leading to new patterns in the complex intersections of overlapping threads. In addition to its visual appeal, this phenomena was to prove a critical step towards Talbot’s invention of the halftone dot, a concept critical to his future work in photomechanical printing. But I digress. This is a pretty good print, still reasonably strong in tone and exhibiting only a couple of edge tears after decades of war and occupation. That in itself would be special, but a pencil annotation on the verso gives additional insight into Talbot’s working practices.

I doubt that Miss Talbot attached much significance to this inscription and certainly the early custodians of this collection in Estonia did not – otherwise they would have placed their inventory numbers elsewhere. The idiosyncratic phonetic spelling of ‘Lowered in H. S. Hott’ betrays the author as Nicholas Henneman, Talbot’s one-time valet and the person who invested his entire future in the promise of photographic printing. Born in Holland and trained in Paris, Henneman was a highly intelligent and cultured man, albeit one untutored in the niceties of English spelling. If you read his writings out loud (at least in your head) they make perfect sense. The ‘H.S.’ here is hyposulphite of soda, sodium thiosulphate in more modern terms, the fixer familiar to generations of photographers as simply hypo. In this instance, Henneman used it ‘hot’ to accelerate the chemical reaction. ‘Lowered’ or ‘lowering’ was Talbot’s method of correcting prints that were too dark. When making prints with photogenic drawing paper (salt prints in today’s lingo) all sorts of factors came into play, variables unintuitive to those who have worked with papers manufactured in the (former) factories of Kodak and Ilford, and particularly alien to those whose own photography is the result of the digital age. For Talbot and Henneman, each sheet of paper had to be coated by hand, using chemicals of varying purity and concentration. Each negative had its own ‘actinic’ density, where not only its darkness but its colour would affect how much photochemically active light it would transmit to the paper. And then there was the quality of the sunlight under which the print was made, not only the changes imposed by the time of day and the season of the year, but also the interference of passing clouds and the filtering caused by pollution in the air. One could add humidity and a host of other factors, but in short, the only way to make a print was to call on past experience and to periodically examine the progress of a print. When one was tending to a dozen or so print frames all at once, errors were bound to occur. One also had to make the print a certain amount too dark, for subsequent fixing bleached it back a bit. If the print came out too light, detail in the highlight areas was irretrievably lost. However, if it came out too dark, it just might be salvaged. In 1841, Talbot complained to Constance about Henneman’s printing: “I must make some criticisms on his performances …his copies of my originals are generally not half strong enough; the fault of being too strong would be much better as I then could lower them, but these are nearly useless from their faintness.” In his Notebook P, Talbot records lowering the tint by applying boiling water and in Notebook Q by subjecting the print to extended exposure to sunshine. Soaking the print in a heated bath of hypo, thereby accelerating the chemical action, was another approach. Conservators are probably shifting unquietly in their seats right now, but obviously these manipulations were not always deleterious. The good condition of this lace after treatment 170 years ago is sufficient proof of that.

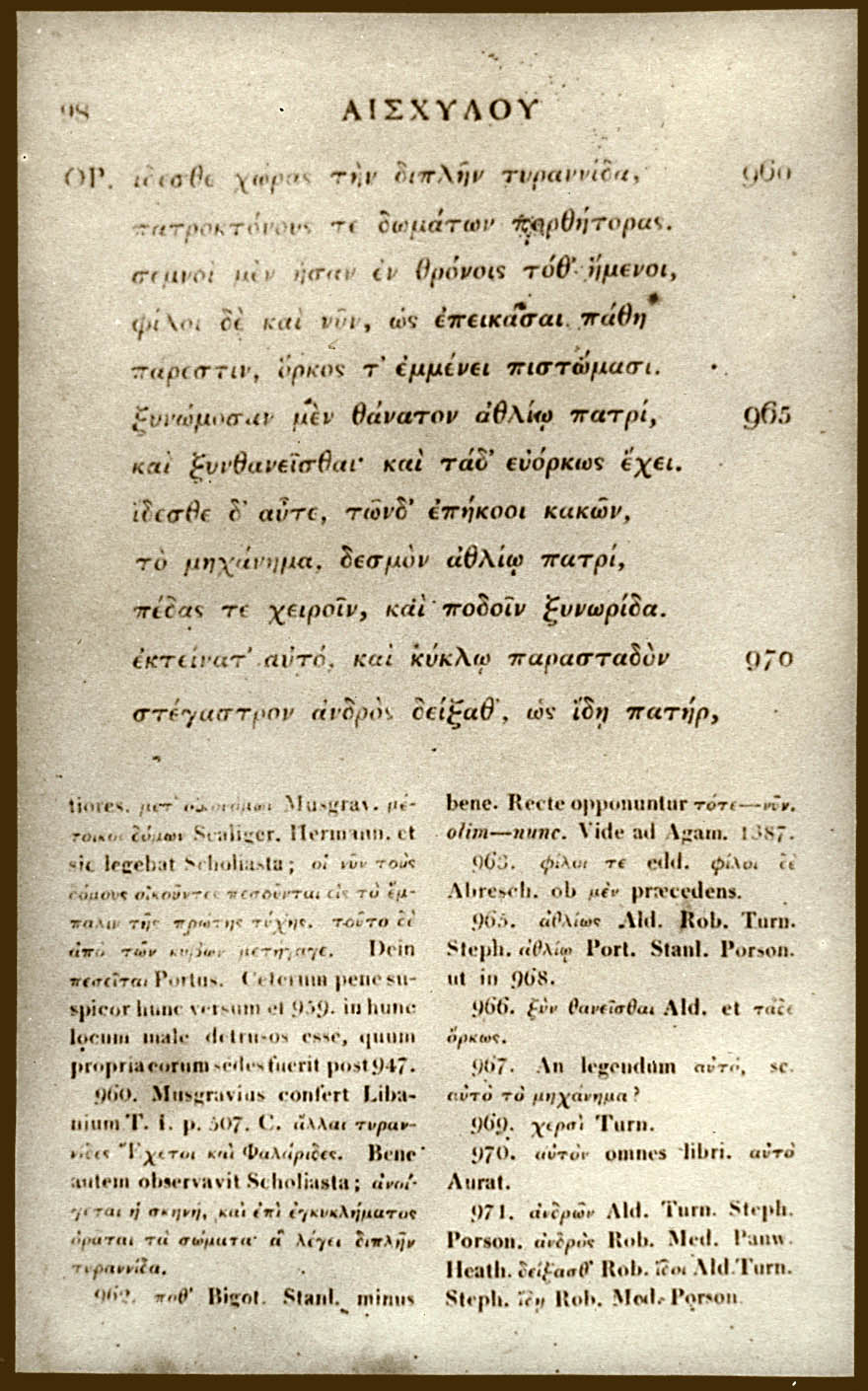

For another print in the Tartu collection we can use Henneman’s printed title: “A copy, diminished in size, of a page in the Bishop of London’s edition of Æschylus.” Aeschylus was the ‘father of Greek tragedy’ and the Bishop of London was his most prolific interpreter. The Bishop was Dr Charles James Blomfield (1786-1857), a correspondent to whom Talbot gave copies of at least two of his books. The idea is so commonplace today that we don’t even recognize it, but photography gave the ability to precisely copy documents, whether they were manuscript or complex typesetting like the above. It could also change the scale of the replication, making it suitable for inclusion in other formats of books. This print also contains a pencil inscription on the verso, one more enigmatic than the above.

The long-ago Estonian cataloguer clearly did not attach any significance to this loopy letter L, writing the inventory number right over it, only to be struck out by some later cataloguer when the system changed. But the pencil L survived. What does it mean? There are at least a dozen Talbot prints worldwide with this large initial, all done with the same flourish. Was it an employee of Henneman, asked to keep track of which prints he made? Or, given the similarity to the L in the Lowered example above, was it possibly an abbreviation for this procedure? I do not know for sure.

In making her distributions in the 1930s, for technical advice and writing Matilda Talbot relied on Alexander Barclay, the Science Museum Keeper who famously sent a lorry to Lacock Abbey in 1934 and packed it with as many originals as he could squeeze in. More on that will have to come in a future story. Barclay’s main interest was in photomechanical reproduction, rather than photography as an art, so it is not surprising that his selections from the Abbey emphasised Talbot’s photogravures and that this was reflected in what he guided Matilda Talbot into donating elsewhere. In addition to supporting material, the Tartu collection comprises ten original salt prints and eleven photographic and photoglyphic engravings.

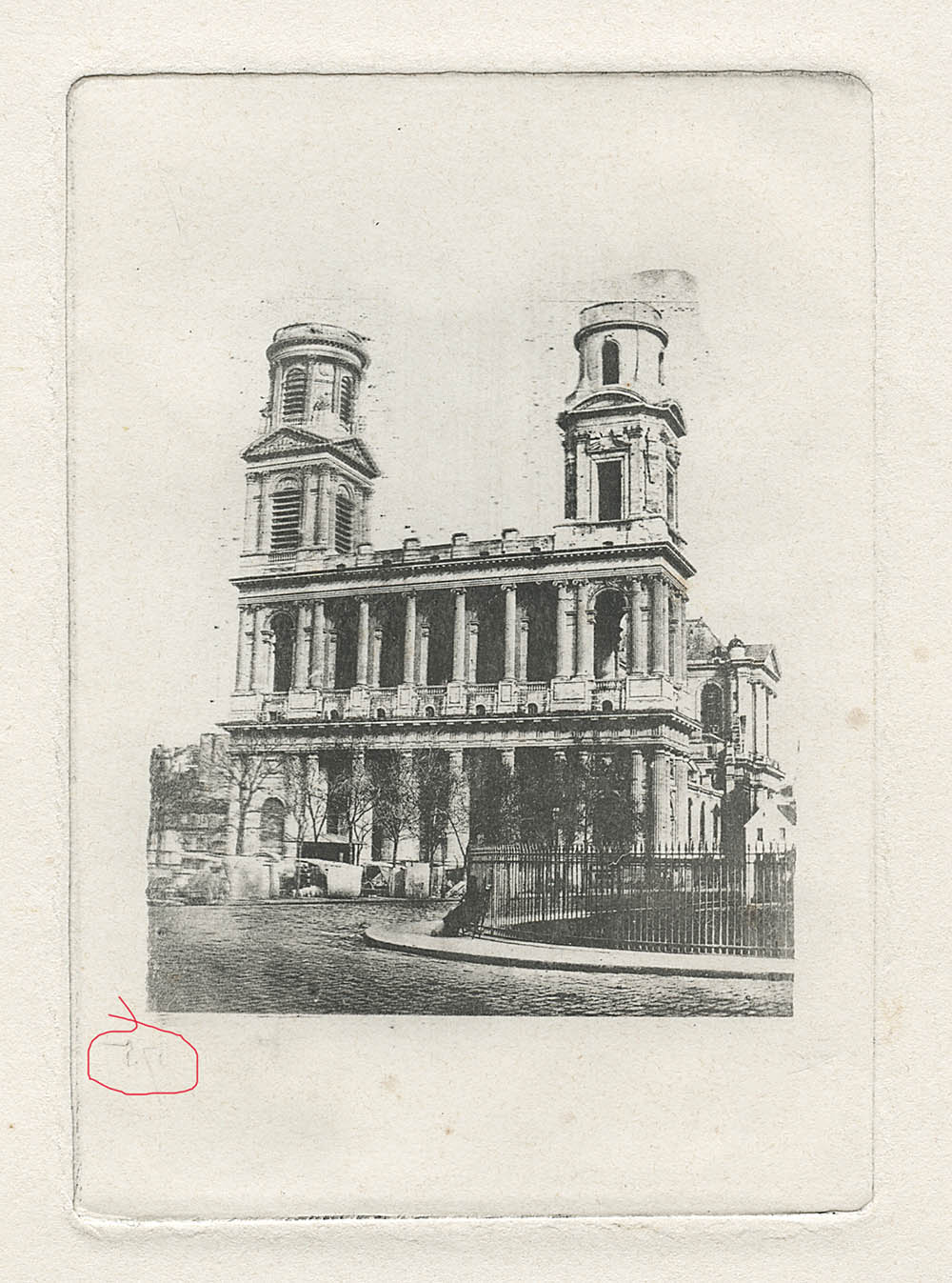

St Sulpice is only slightly smaller than Notre Dame and is one of Paris’s most important churches. It is not a surprising subject, for Talbot obtained glass positives from various Parisian photographers – they were perfect for his experiments in photogravure. Over a span of nearly three decades, Talbot made many hundreds of steel and copper plates and thousands of proof prints. Little is known at present about many of these, but a few carry a hairline trace of an experiment number that was cut into the printing plate with a diamond. The number prints in reverse and being so fine is often tantalizingly illegible. In this instance though, we can tease a magnified image out of the paper fibers just enough to make it out (reversed here for clarity).

Using that number, we can turn to Talbot’s voluminous notes on his experiments. On 20 November 1859, he cited this particular plate:

“St Sulpice. Pict[ure] made many days ago. This power of keeping is a most conven[ient] property, as it enables the process to be conducted in separate portions, at intervals, as conven[ien]ce may suggest.” The picture that he is referring to is the photographic image on the steel plate. It was used to resist his etchant and then totally removed, leaving a plate with no active photographic chemicals to raise havoc over time and one that could be employed in a conventional printing press with conventional ink. It was the future of photography.

Returning to my soapbox, it is easily understood why these pencil scribblings were dismissed in the past, if perceived at all. Aside from the fact that every one of Talbot’s and Henneman’s prints and negatives must contain traces of their DNA, each is potentially important for what it can contribute to the totality of the story. One of the functions of the Catalogue Raisonné is to observe and collate previously unseen factors such as these annotations and to link these to Talbot documents and other sources.

And now, I wish to deputise the readers of this blog. I’ve looked at a lot of Blomfield’s books on Aeschylus – and there are a great many of them – but in general they measure a pretty conventional 22 or so cm. tall. Talbot’s reproduction of an obviously trimmed page is 17 cm. tall, so Henneman’s observation that it was “diminished in size” must mean that the original was substantially larger. We have the clue of the page number and the passage numbers. Do any of our readers know which edition of which book provided the original subject? Or perhaps you know somebody who will know. I would very much like to hear from you.

And now, I wish to deputise the readers of this blog. I’ve looked at a lot of Blomfield’s books on Aeschylus – and there are a great many of them – but in general they measure a pretty conventional 22 or so cm. tall. Talbot’s reproduction of an obviously trimmed page is 17 cm. tall, so Henneman’s observation that it was “diminished in size” must mean that the original was substantially larger. We have the clue of the page number and the passage numbers. Do any of our readers know which edition of which book provided the original subject? Or perhaps you know somebody who will know. I would very much like to hear from you.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • I would like to thank Sulo Lembinen, Curator of photographic collections for the University of Tartu Library, for making my recent visit there so productive and for providing crucial information. And thanks to Dr Anthony Hamber (whose mother was Estonian) for spending years patiently encouraging me to go there. • Matilda Talbot, My Life and Lacock Abbey (London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd, 1956); the title is quoted from p. 235. Eleonore Marie Kristine Hünerson (1890-1949) fled to Germany in 1944 and then to England in 1947 to be employed as a schoolteacher in London. Her husband Jaan Hünerson was arrested by Soviet occupation authorities in 1941 and shot in a prison camp in Russia in 1942. The daughter Helgi (1911-1989) who had stayed at Lacock Abbey was married to Elmar Siegfried Just, who died in Russia in 1941. • A very useful text on Matilda’s donation was written by a professor of organic chemistry who illustrated all the holdings: Tullio Ilomets, “W.H.F. Talbot’s Original Examples of his Discoveries in Photography and Photo-engraving in the Scientific Library of Tartu State University,” Tartu Ülikooli toimetised, v. 248, 1969, pp. 153-163. Additional information on the donation is in Peeter Tooming, “Original Talbot Photographs in Estonia,” History of Photography, v. 9 no. 2, April-June 1985, pp. 162-167. • WHFT, Black Lace, salt print from a photogenic drawing negative, Special Collections, the University of Tartu, f42.s6; Schaaf 3803. • WHFT, No. 47. A copy, diminished in size, of a page in the Bishop of London’s edition of Æschylus, salt print from a calotype negative, Special Collections, the University of Tartu, f42.s12; Schaaf 3804 • Even with the bustle of the public introduction of photography, Talbot maintained his other interests. In 1838 he presented Blomfield with a copy of his Hermes: or Classical and Antiquarian Researches, No. 1. (London: Longman, Orme, Green, Brown & Longman, 1838); see Talbot Correspondence Document no. 03276 . In 1839 he sent a copy of his The Antiquity of the Book of Genesis; Illustrated by Some New Arguments (London: Longman, Orme, Green, Brown, and Longman, 1839); see Doc. no. 05767. • WHFT to Constance, 13 June 1841, Doc. no. 04278. • WHFT, St Sulpice, print from an experimental photoglyphic engraving plate, Special Collections, the University of Tartu, f42.s13. • Steel plate no. 375 survives in the Talbot Collection, the National Media Museum Bradford, 1937-5270. Many of Talbot’s experimental notes, including the one illustrated here, are in this collection. • Because of their unique nature and voluminous quantities, Talbot’s photogravures are not part of the present Catalogue Raisonné project (although I wish they could be). Some information on them can be found in my essay “ ‘The Caxton of Photography’: Talbot’s Etchings of Light,” in Mirjam Brusius et. al., William Henry Fox Talbot: Beyond Photography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).