Although we have such wonderful documentation on many of Talbot’s productions, precisely and reliably dating his photographs can be difficult. I’m often asked to hazard a guess on the most likely date for a particular image. In the case of this panoramic view of the River Thames in London, based solely on the visual evidence, one really should say that Talbot took his photograph not long after 1512.

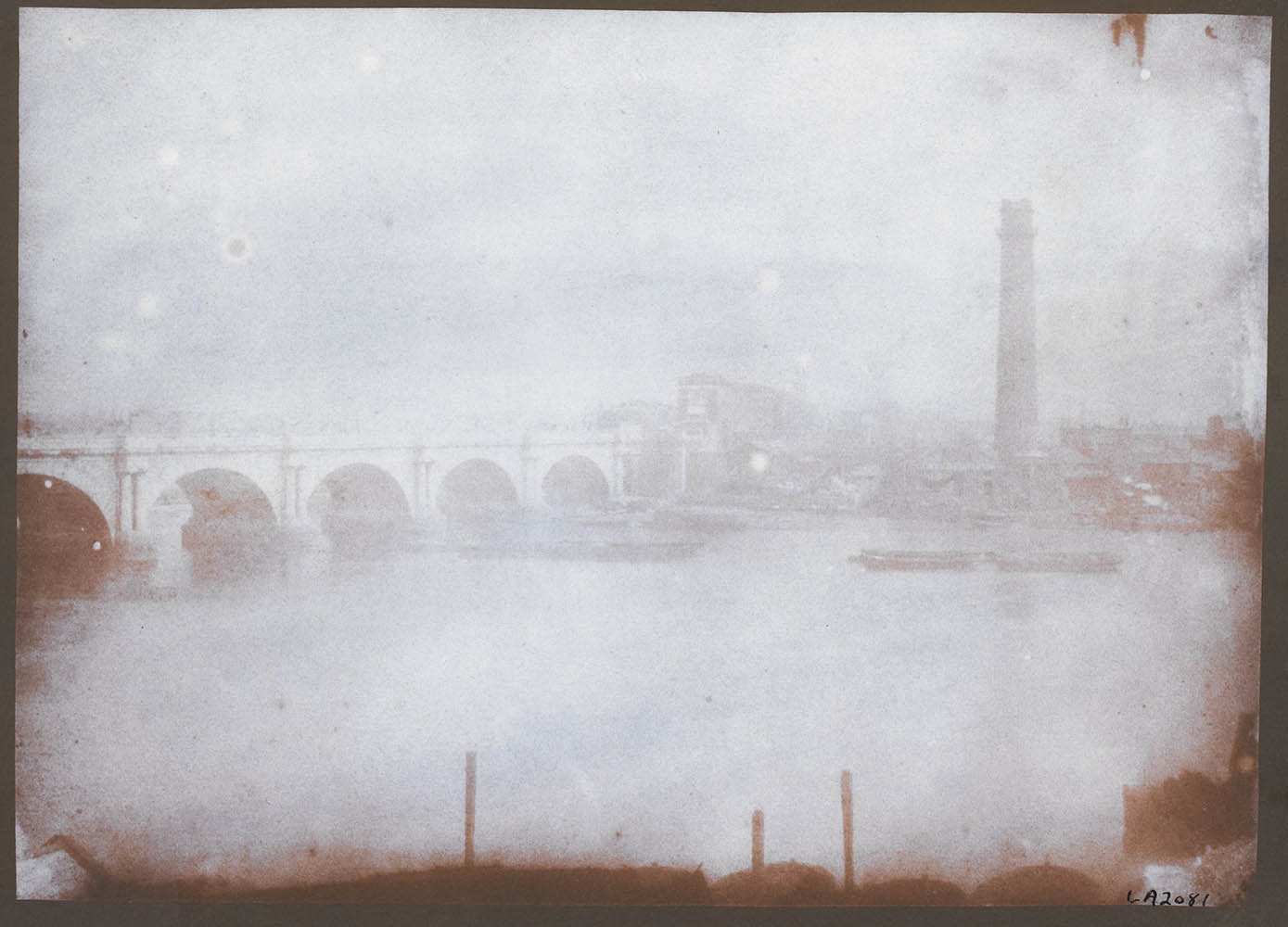

Looking across the River Thames, from Talbot’s flat on Cecil Street

The important river commerce on the Thames is marvelously depicted here, brought into sharp relief by Talbot’s choice of backlighting. Dominating the landscape is Westminster Abbey, displyed as it was meant to be seen in medieval times, unthreatened by competing buildings. It is a sight that none of us have even seen, but equally, it would have been novel to Talbot as well. In 1512, fire almost completely destroyed the medieval Westminster Palace, more familiarly known as the Houses of Parliament. It was soon built back up, so one would be tempted to date this image to the early 16th century. Just on the right of the frame, however, is the roof of Inigo Jones’s 1612 Banqueting Hall, so we have a contradiction. But if we take this down to the age of photography, where is the scene familiar to us today? Whatever has happened to Big Ben?

Immediately deflating our conjectures, of course, is the ‘June 1841’ dating in the bottom of the negative, clearly showing through on the print. That places this photograph in that magical little slice of time after the Houses of Parliament again burned to the ground on 16 October 1834. The foundation stone for Charles Barry’s replacement was set on 27 April 1840 and the complex familiar to us today was largely completed within a decade. Barry was assisted by a young Augustus Pugin and it is ironic that Pugin’s last commission was the Clock Tower, the one that holds Big Ben, completed in 1858. Victoria Tower, the ‘fireproof repository for books and documents, ‘ was added in 1860. I am always struck by how many of Talbot’s photographs, at first appearing timeless, are resolutely documentary of the new life around him. The summer of 1841 – not much before, not long after – is the only time in history that this photograph could have been taken.

Just to the left of Westminster Abbey we can see a fortuitous survivor of the 1834 fire, Westminster Hall, the finest timber roofed building in Europe. The bridge on the left is the Westminster Bridge, built in 1750; in 1854, construction would begin on its replacement, in use to this day. This was perhaps the busiest point for river traffic on the Thames. The foreground is Hungerford Market. The tables are likely those of a public house, offering a spectacular and ever-changing view along with a pint. Within four years, Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s pioneering Hungerford Bridge would extend from here, blocking this view. Such was the pace of progress that both it and the market would be swept away in 1859, destroyed by the railroads’ need for Charing Cross Station, replaced by the unloved Charing Cross Bridge. As our eye travels through to Westminster Abbey, we see Percy Wharf, Middle Wharf, Draw Dock, Crown Wharf and Great Scotland Yard Wharf.

Talbot had gone to London specifically to photograph the metropolis and for this purpose hired a flat in Cecil Street, an area familiar to him from his visits to nearby Kings College and the Society of Arts. The Art Deco Shell Mex House (with its huge clock, nicknamed ‘Big Benzene’) now stands on the spot. On 15 June 1841, his mother, Lady Elisabeth recorded in her diary that she “went to see Henry make Calotypes in his new domicile in Cecil Street.” As he explained to his wife Constance that evening, “my windows in Cecil St. command a good view of the river but unfortunately I find that the London atmosphere prevents a good result, even the fog is hardly visible to the eye.” It is perhaps in trying to overcome the effect of the notorious London smog that Talbot hit on the idea of using the backlighting. If anything, the smog strengthens his composition, allowing the serpentine glare of the water to stand out. Talbot’s favourite Uncle William acknowledged the power of his London views, but being more of a romantic, wrote that “I have received your beautiful Calotypes would not the Avon at Clifton do as well as the Thames at Wapping?” Perhaps his wish was partially granted, for in 1859 the chains from the Hungerford Bridge were recycled for the Clifton Suspension Bridge over the Avon.

Talbot took other photographs from his Cecil Street base. With the trip even more productive than he had expected, he asked Constance on 16 June to command Nicolaas Henneman “to come up to Town by an early train on Friday morning. He had better bring with him 2 dozen sheets of iodized paper which Porter has been preparing” (Charles Porter was a servant frequently called on to prepare photographic materials). In this view, the original Waterloo Bridge (opened in 1817 and replaced in the 1940s), leads to the 1826 Shot Tower of the Lambeth Lead Works. This tower fascinated other artists, such as J.M.W. Turner, and it is not surprising that Talbot made his own depiction of it (the Tower was demolished in the 1960s). So far we know of five surviving images taken from different windows on Cecil Street. By the summer of 1841, Talbot was flexing his photographic muscles, exploring what his calotype could do.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, River Thames in London, from Talbot’s Cecil Street flat, salt print from a calotype negative, June 1841, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-366/50: Schaaf 3705. While the negative for this has not been located, there are three other known prints. • Lady Elisabeth’s diary is in the Lacock Abbey Collection, Wiltshire and Swindon Archives, Chippenham. • Henry Talbot to Constance Talbot, 15 June 1841. Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, LA41-39, Talbot Correspondence Document no. 04282. • William Thomas Horner Fox Strangways to WHFT, 2 November 1841. LA41-64, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, Doc. no. 04353. • The request for more paper was added in a postscript dated 16 June; WHFT to Constance Talbot, 15 June 1841. LA41-39, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library; Doc. no. 04282. • WHFT, The Waterloo Bridge and the Shot Tower, salt print from a calotype negative, June 1841; Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, LA2081; Schaaf 1384). The negative for this was formerly in the collection of Harold White and is illustrated in Schaaf, Sun Pictures Catalogue Three: The Harold White Collection of Works by William Henry Fox Talbot (New York: Hans P. Kraus, Jr., Inc., 1987), plate 49. • The present photograph and some other Talbot’s are considered in context in a dated but stimulating book: Gavin Stamp, The Changing Metropolis: Earliest photographs of London, 1839-1870 (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Viking, 1984). I hope that he makes good on his promise to update this some day.