In this wonderfully descriptive tableaux vivant, we have an early virtual reality presentation of Nicolaas Henneman’s photographic establishment in the market town of Reading, about halfway between Lacock Abbey and London. Possessed with a courageous if overly optimistic faith in Talbot’s new discovery, Henneman had taken the highly unusual risky step of separating from his master’s service in late 1843 to open the world’s first full-service operation dedicated to photography. We have examined this business earlier and today I want to take a closer look at just this panoramic picture.

In this wonderfully descriptive tableaux vivant, we have an early virtual reality presentation of Nicolaas Henneman’s photographic establishment in the market town of Reading, about halfway between Lacock Abbey and London. Possessed with a courageous if overly optimistic faith in Talbot’s new discovery, Henneman had taken the highly unusual risky step of separating from his master’s service in late 1843 to open the world’s first full-service operation dedicated to photography. We have examined this business earlier and today I want to take a closer look at just this panoramic picture.

One would think that a panorama of this detail and significance would be very well understood and documented, but it poses far more questions than it answers. Some aspects are obvious. The setting is on Russell Terrace in Reading, a backyard one can still observe with a little careful acrobatics involving fences, walls and negotiations with responsible dogs. In this view, the trees are devoid of leaves, giving an indication of season, but the open windows on the houses to the right imply moderate temperatures. The shadows establish the time of day as afternoon. The setting is appropriately out of doors, where the sunlight was, the essential currency for photography. The distinctive visage of Nicolaas Henneman himself is third from the right. There don’t appear to be any stealthy black cats on the prowl. However, in all the various forms of documentation that I have looked at over the years – Talbot’s own letters and notebooks, Henneman’s fragmentary business records, invoices, comments published and unpublished from contemporaries, I have never found a single reference to what must have been a very elaborately prepared and choreographed shooting session. Why was this image made? By whom? When?

The original full-plate calotype negatives survive in surprisingly good condition. The earliest date would be the winter of 1843/44 and the latest that of 1846. In addition to the negatives, the finest set of prints from them was owned by Harold White (who found it necessary to intensify one half). Other prints are in Royal Photographic Society and Science Museum collections in the National Media Museum and the Smithsonian. There was a mounted hand-coloured double print in Lacock Abbey. One print has a pencil number ‘217’ on verso in the style found on many other Reading prints but its significance is unknown.

The original full-plate calotype negatives survive in surprisingly good condition. The earliest date would be the winter of 1843/44 and the latest that of 1846. In addition to the negatives, the finest set of prints from them was owned by Harold White (who found it necessary to intensify one half). Other prints are in Royal Photographic Society and Science Museum collections in the National Media Museum and the Smithsonian. There was a mounted hand-coloured double print in Lacock Abbey. One print has a pencil number ‘217’ on verso in the style found on many other Reading prints but its significance is unknown.

(Pam Roberts cries out: ‘That stamp was already there when I arrived’)

(Pam Roberts cries out: ‘That stamp was already there when I arrived’)

There is no evidence that Talbot was the instigator of this and he may well have not been there when it was taken (more on that in a moment). Geoff Batchen observes that this is a baldly commercial propaganda piece for a capitalistic operation and that as a gentleman Talbot would have been hesitant to get involved. Without disagreeing, I would counter that Talbot was always extremely supportive of his ex-servant and might have been persuaded to lend his reputation as assistance. Many years ago when I was discussing this image with Gordon Baldwin we mused on the loopy Xs in the corners. They are registration marks for the panorama that are typical of the work of the Rev Calvert R Jones, who was particularly fond of ‘joiners’ as he styled them. We’ll be talking about Jones more in the future but for now suffice it to say that he almost took over the management of Henneman’s operation, saved only by suddenly coming into an unexpected inheritance. The loopy Xs carried on, apparently a standard practice in Reading.

Starting at the left, we can examine the typical wooden box camera that was by then being offered by various mechanics. How many of my older readers remember the Time-O-Lite hand-wound timers once used in darkrooms? Its predecessor sits on the tailboard of the camera, ready to guide the operator in how long to remove the lens cap (there was no shutter). The tripod was not a separate device, but rather the type where three legs socketed into the base of the camera. The garden shed was a glasshouse, used to control the light while preparing materials, tasks that the assistant standing inside would have been kept busy with – for now, he is standing by with another calotype negative carrier for the back of the camera. Drapes cover the windows of the house itself, creating more dark workspace.

Starting at the left, we can examine the typical wooden box camera that was by then being offered by various mechanics. How many of my older readers remember the Time-O-Lite hand-wound timers once used in darkrooms? Its predecessor sits on the tailboard of the camera, ready to guide the operator in how long to remove the lens cap (there was no shutter). The tripod was not a separate device, but rather the type where three legs socketed into the base of the camera. The garden shed was a glasshouse, used to control the light while preparing materials, tasks that the assistant standing inside would have been kept busy with – for now, he is standing by with another calotype negative carrier for the back of the camera. Drapes cover the windows of the house itself, creating more dark workspace.

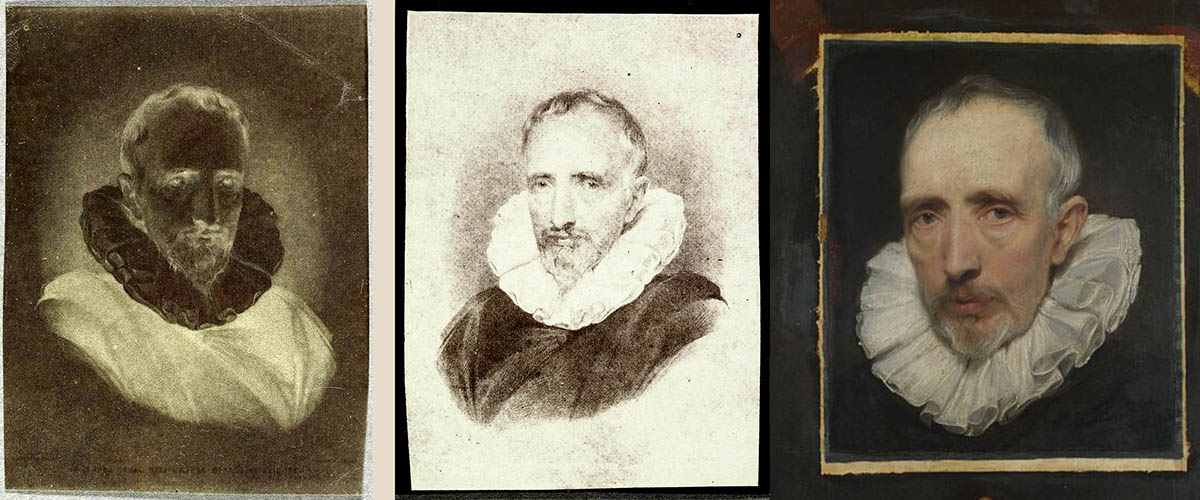

The patient sitter is this case is a probably Francis William Wilkin’s lithograph of Anthony van Dyck’s Portrait of Cornelis van der Geest. Aside from the niceties involved in borrowing the original oil on oak panel, Henneman would have had difficulty accurately reproducing the colours. This important task of replicating artwork would soon be the basis for his contribution to Stirling Maxwell’s Annals of the Artists of Spain.

The patient sitter is this case is a probably Francis William Wilkin’s lithograph of Anthony van Dyck’s Portrait of Cornelis van der Geest. Aside from the niceties involved in borrowing the original oil on oak panel, Henneman would have had difficulty accurately reproducing the colours. This important task of replicating artwork would soon be the basis for his contribution to Stirling Maxwell’s Annals of the Artists of Spain.

In the centre we witness what was already emerging as one of the most important tasks of photography, that of capturing the human likeness. Our sitter is comforted not by the fork arrangement so commonly seen gripping the necks of daguerreian subjects, but rather by resting the back of his head on an iron hoop to steady him for the several second exposure. The composition and focus have been settled and the ground glass has been flipped up to allow insertion of the negative paper holder. The confident operator eschews the use of a timer, relying instead on experience. Surely this must be William Henry Fox Talbot himself, master of ceremonies. It is a pose so well known that a bronze statue near Lacock Abbey memorialises it. But is this really Talbot?

In the centre we witness what was already emerging as one of the most important tasks of photography, that of capturing the human likeness. Our sitter is comforted not by the fork arrangement so commonly seen gripping the necks of daguerreian subjects, but rather by resting the back of his head on an iron hoop to steady him for the several second exposure. The composition and focus have been settled and the ground glass has been flipped up to allow insertion of the negative paper holder. The confident operator eschews the use of a timer, relying instead on experience. Surely this must be William Henry Fox Talbot himself, master of ceremonies. It is a pose so well known that a bronze statue near Lacock Abbey memorialises it. But is this really Talbot?

Geoff Batchen and I have long agreed that if this was Talbot then he missed his greatest entrepreneurial opportunity by wasting time on his discovery of photography rather than concentrating on marketing his hair-regeneration therapy. The face from the panorama is here flanked by two of Richard Beard’s daguerreotype portraits of his contemporary. They were made in the first part of the 1840s, roughly contemporaneous with the calotype but two or three years earlier. By the time of the calotype, Henry’s hair had shown remarkable re-growth and he has even triumphed over the bags under his eyes – botox? Which leads us to the question of just who this central figure in the panorama might be? Work on that one for a minute.

Geoff Batchen and I have long agreed that if this was Talbot then he missed his greatest entrepreneurial opportunity by wasting time on his discovery of photography rather than concentrating on marketing his hair-regeneration therapy. The face from the panorama is here flanked by two of Richard Beard’s daguerreotype portraits of his contemporary. They were made in the first part of the 1840s, roughly contemporaneous with the calotype but two or three years earlier. By the time of the calotype, Henry’s hair had shown remarkable re-growth and he has even triumphed over the bags under his eyes – botox? Which leads us to the question of just who this central figure in the panorama might be? Work on that one for a minute.

The all important operation of printing the negatives is shown next. Of course one needs a top-hatted supervisor for such critical operations, but the boy would have been kept busy with all the work. The portable rack could be positioned to best capture the erratic rays of the sun. A dozen frames sandwich sensitive photogenic drawing paper beneath the paper calotype negative, pressed into tight contact by a sheet of glass on the front and screws or wedges on the back. As the sun ducked in and out of clouds, the printer had to watch the progress of each negative, for each would pass somewhat different amounts of light through to the paper. Each negative, of course, could make only one print at a time, a forced opportunity for diversity in printing the examples for the Art-Union, where different prints could be distributed, but a decided production chokehold when identical prints were required for The Pencil of Nature or Sun Pictures in Scotland.

And finally we come to Nicolaas Henneman himself. By now the camera and timer are familiar and here he demonstrates the important task of copying sculpture, turning a plaster model of The Three Graces into a well-modeled two-dimensional print. Woodcuts and engravings, while extensively employed for copying sculptures, were particularly unkind to them. Their digital nature – the inescapable choice of either hard lines of ink or spaces of bald paper – failed to capture sculpture’s great capacity for being shaped by light. Photography was sculpture’s comfortable cousin.

And finally we come to Nicolaas Henneman himself. By now the camera and timer are familiar and here he demonstrates the important task of copying sculpture, turning a plaster model of The Three Graces into a well-modeled two-dimensional print. Woodcuts and engravings, while extensively employed for copying sculptures, were particularly unkind to them. Their digital nature – the inescapable choice of either hard lines of ink or spaces of bald paper – failed to capture sculpture’s great capacity for being shaped by light. Photography was sculpture’s comfortable cousin.

But what of the mysterious device at the right? Beaumont Newhall and Arthur Gill and others I think correctly identified this as a type of Focimeter. John Towson (surely a future blog) identified a problem with the daguerreotype just week’s after Daguerre’s disclosure of his process. As sharp as they were, the images often fell short, and Towson pointed to the problem as originating in the difference between the chemical or photogenic rays of light and those of the luminous or visible or colorific ones. All early photographic materials responded almost exclusively to light near the blue end of the spectrum. Our eyes are more responsive to the red and yellow end. Simple lenses focused different wavelengths of light at a different point. Thus, if one focused a camera to optimal sharpness for the eye, the wavelengths that were going to do the job on the photographic material were focused on a slightly different plane. Towson explained that Daguerre’s camera “would be most correct if the chemical rays were identical to the luminous rays” but that ” in order to obtain the neatest effect… the camera should be adjusted to the chemical rays.” The operator had to focus the lens for what appeared to be the sharpest image, then by experience slightly change the focus for the benefit of the photograph.

The title of this blog is borrowed from Charles Dickens’s magazine Household Words, where this problem of focus was explained in 1853, concluding that “for this, allowance has to be made in practice, and accurate instruments for ascertaining the true photogenic focus have been invented, one by M. Claudet, and another by Mr. G. Knight. They are called Focimeters. There are hidden mysteries, however, connected with this portion of the subject.”

The introduction of achromatic lenses, the type most likely in use by the time of this photograph, ameliorated this problem somewhat but did not eliminate it. Antoine Claudet devised a Focimeter, a three-dimensional arrangement of numbered fan blades. In a somewhat later daguerreotype, he is seated next to his instrument with his son Henri standing behind. The operator would visually focus on one of the numbered blades and then take the daguerreotype or photograph. Upon development, he would then observe which of the numbered blades came out sharpest. This quantified the exact difference in focus required for each lens and working distance and allowed the operator to mark the bed of the camera. In use, the focus would be made sharp to the eye, the sliding boxes then adjusted to the appropriate mark and a sharper photograph would result. Claudet also felt that this would encourage ‘artistic harmony’ by guiding the photographer in how much to keep foreground and background elements in focus.

The introduction of achromatic lenses, the type most likely in use by the time of this photograph, ameliorated this problem somewhat but did not eliminate it. Antoine Claudet devised a Focimeter, a three-dimensional arrangement of numbered fan blades. In a somewhat later daguerreotype, he is seated next to his instrument with his son Henri standing behind. The operator would visually focus on one of the numbered blades and then take the daguerreotype or photograph. Upon development, he would then observe which of the numbered blades came out sharpest. This quantified the exact difference in focus required for each lens and working distance and allowed the operator to mark the bed of the camera. In use, the focus would be made sharp to the eye, the sliding boxes then adjusted to the appropriate mark and a sharper photograph would result. Claudet also felt that this would encourage ‘artistic harmony’ by guiding the photographer in how much to keep foreground and background elements in focus.I believe that what is being used in the panorama is a primitive early form of a type of Focimeter. You may find it a bit difficult to make out, but Henneman’s favourite term of ‘Sun Pictures’ is emblazoned on each segment.

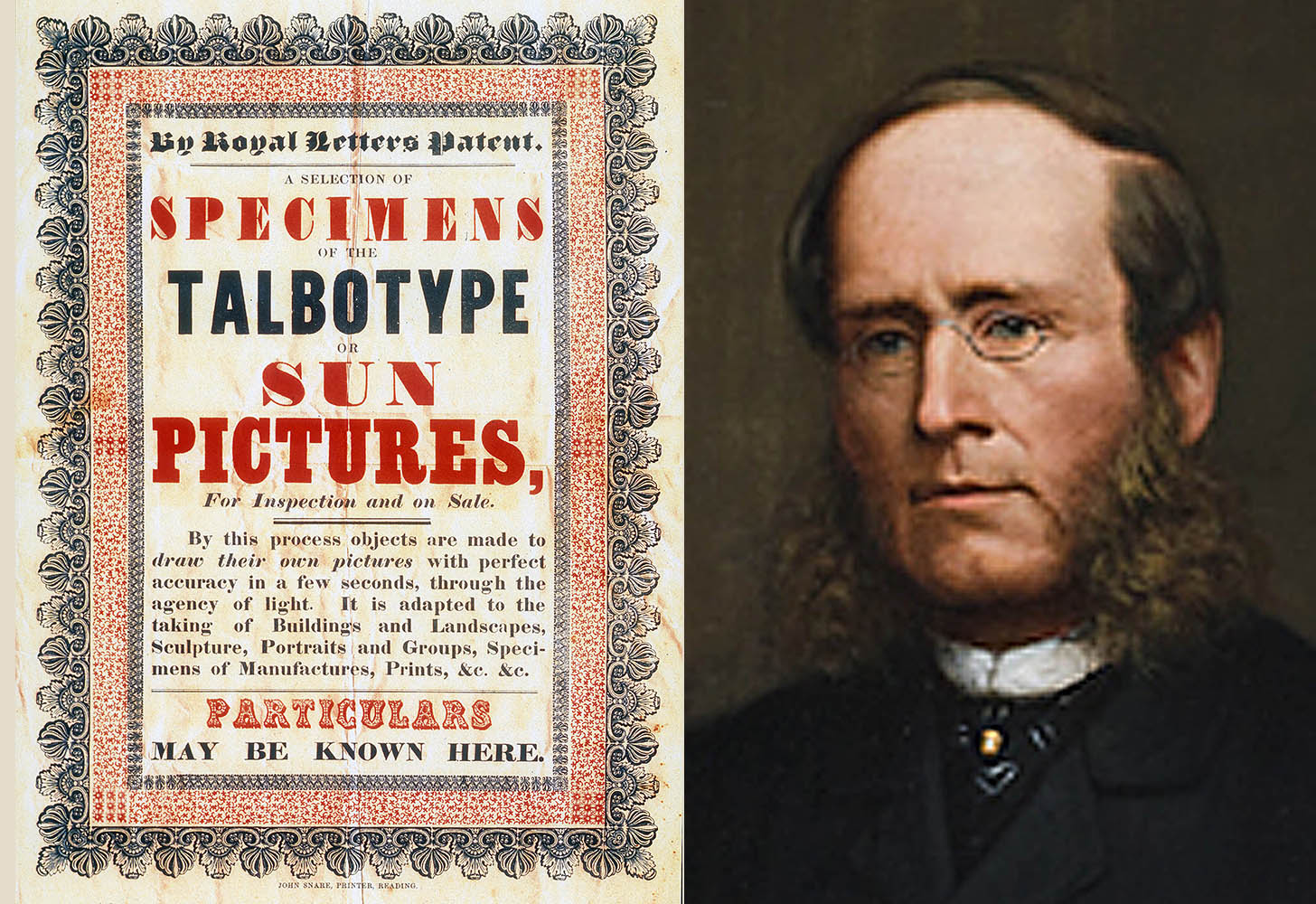

So we return to the questions of the who/when/why of this panorama.? We have not had a blog yet on Benjamin Cowderoy, but we will. A Reading-based land agent, accountant and businessman, when Calvert Jones became unavailable to take over management of Henneman’s establishment Cowderoy stepped in. His first involvement was in the spring of 1846 but his relationship with Talbot had fallen apart by the end of that year. He was particularly proud of his promotional activities, recalling much later in life the lively broadside that he designed for Henneman’s business. In 1861 this portrait painter was perhaps a bit generous with his hairline, for there were indications even by the mid-1840s that, like Talbot, he had some thinning on top. Forced to express an opinion, I would squiggle about a bit and then say that I think that Cowderoy acted in the role of film director, possibly earlier as script writer or talent scout, just maybe as an actor on the set.

So there remain many “hidden mysteries … connected with this … subject.” Who will take it up?

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Composite panorama courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, New York. It was derived from Harold White’s prints, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Schaaf 1596 & 1597. Unknown photographer, Panorama of Henneman’s establishment at Reading, calotype negatives, winter 1846?, the Royal Photographic Society Collection, National Media Museum, Bradford, RPS025242 and RPS025243, Schaaf 1596 & 1597. • Geoffrey Batchen, “The Labor of Photography,” Victorian Literature and Culture, v. 37, 2009, pp. 292-296. • The van Dyck is discussed in Hilary Macartney and José Manuel Matilla , editors, Copied by the Sun: Talbotype Illustrations to the Annals of the Artists of Spain by Sir William Stirling Maxwell (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2016), pp. 86 and 93. Nicolaas Henneman?, Copy of a lithograph of a van Dyck, calotype negative and salt print, winter 1846?, the National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-4482 & 1937-4485; Schaaf 632. Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Cornelis van der Geest, oil on panel, the National Gallery, London. • Richard Beard, William Henry Fox Talbot, daguerreotypes, ca. 1842-1843, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London. • Nicolaas Henneman, Boy with Printing Frames at the Reading Talbotype Establishment, salt print from a calotype negative, ca. 1844, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-3127, Schaaf 3242. • Beaumont Newhall, “The Focimeter,” Image, v. 1 no. 2, February 1952, pp. 1-2. • Henry Morley and William Henry Mills, “Photography,” Household Words, v. 7 no. 156, 19 March 1853, p. 60. • Advertising Broadside for Nicolaas Henneman, ca. 1846, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, New York. • H F Allkens, Benjamin Cowderoy (detail), oil, 1861, St Kilda Town Hall.