This marks the first contribution by our newest Advisory Board member, Dr Anthony Hamber. Anthony is a leading expert on photographically illustrated books and is currently working on a book and exhibition on today’s topic. One of the illustrations below is from the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, and I cannot let pass this opportunity to congratulate my old friend Julian Cox on just being named its Chief Curator. Although his remit is broad, Julian has a strong background in photography and I hope he gets a chance to bring this out. Whilst at the J Paul Getty Museum he was instrumental in assisting me with the fledgling Catalogue Raisonné.

guest post by Anthony Hamber

In the previous blog, our esteemed Director concluded that “October was indeed a good month for Henry Talbot.” That may well have been true for some time but October 1851 marked the start of an Annus horribilis for Henry. His torture had recently started, for on 9 August his beloved half-sister Horatia died from the effects of childbirth. This event alone would have been sufficient to colour Talbot’s enjoyment of the Great Exhibition but more was to come.

The 15th of October 1851 marked the closure of The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, held in the Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park. It had been enormously successful, having had more than six million visitors during its nearly six months’ run. Henry Talbot, amongst others, recognised the event as a pivotal moment in the progress of photography. It should have provided an opportunity for Talbot to promote and consolidate his achievements. Instead, he became deeply embroiled in a dispute with the Exhibition’s Royal Commissioners and its Executive Committee.

Talbot particularly clashed with Henry Cole, destined to become the first Director of the South Kensington Museum (now known as the Victoria & Albert Museum). The battle centred on Talbot’s attempt to secure an official photography and printing contract that protected his calotype patent rights. His real reason for doing this was out of loyalty to his former servant, Nicolaas Henneman, who had bravely set out to make a business out of photography. Initially,Henry Talbot had been so intrigued by this opportunity to promote photography before an international audience that in February 1850 he was considering offering a “considerable prize” of £100 for the best specimen of photography on paper and a similar amount for the best daguerreotype exhibited. This was a remarkably even-handed gesture in the light of the rivalry between paper-based processes and the daguerreotype. As a result of the rancor that developed between the officials and Talbot, sadly these prizes were never to materialise.

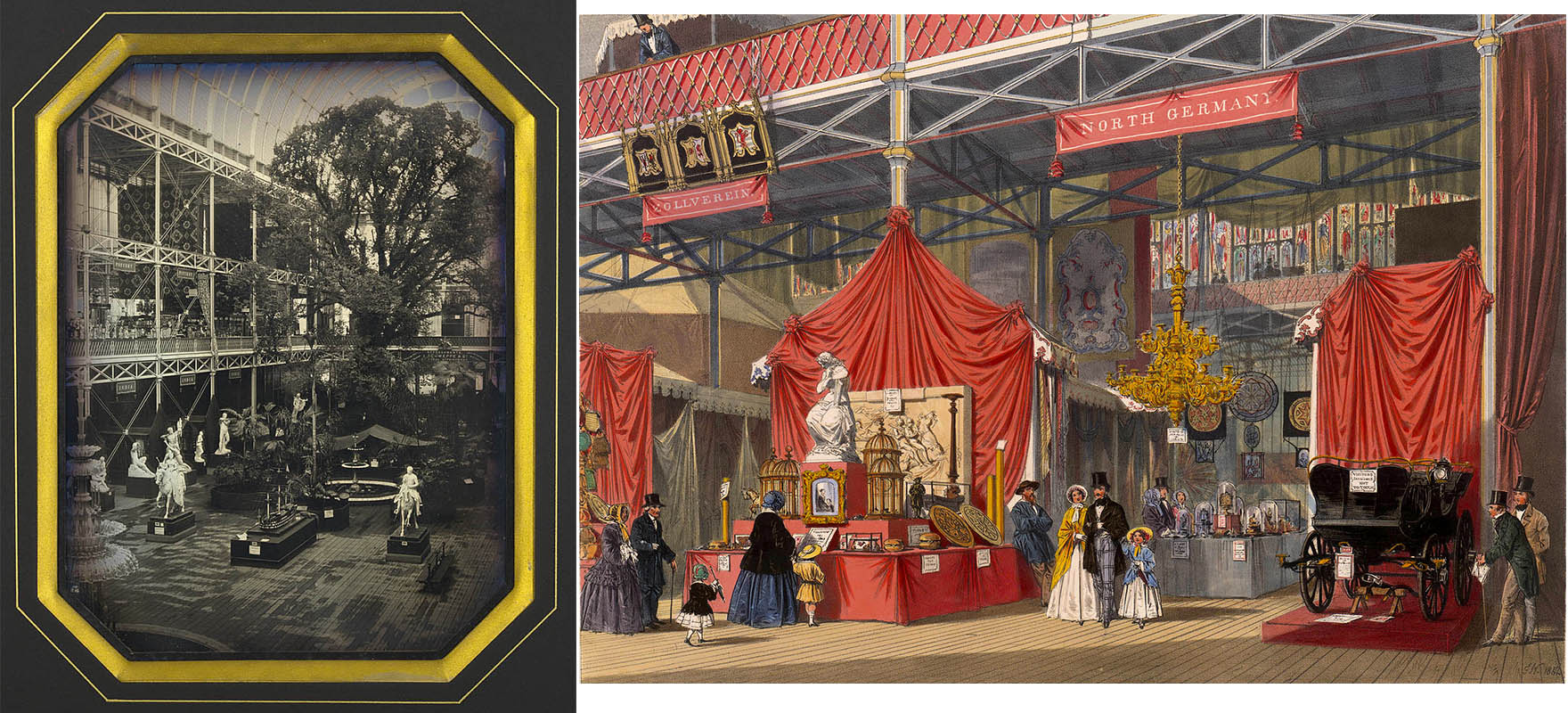

Henry’s most vexing and stressful issue was the securing of the contract to take and print photographs for the special photographically-illustrated presentation sets of the Reports by the Juries. The officials might have turned to other methods of illustration. Daguerreotypes could present exacting detail. Lithographs exploited colour and artistic license to emphasise desired aspects of the displays.

However, in an evolving industrial age, hand-drawn lithographs lacked the truthfulness that had come to be expected at least in part by the extraordinary detail of the daguerreotype. But daguerreotypes were unique images, each done on a silvered sheet of copper and hardly suitable for inclusion in an edition of books, no matter how deluxe.

The making of illustrations by artists was only permitted between 6AM and 9AM, before the Exhibition opened, and also on Sundays when it was closed to the public. Photography suffered from a number of disadvantages. The sketch artist could continue his work in relatively gloomy light. He could ignore clouds of dust and distracting backgrounds. The photography for the Reports took place mainly from August onwards, largely as a result of the photographs having to be of prize winning exhibits, probably unofficially confirmed in late July or early August. The work was challenging given the drop in the levels of daylight with the onset of autumn.

Aware of the commercial opportunities offered by the influx of visitors to London, in January 1851 Talbot wrote to Friedrich Carl Vogel (1806-1865), a German calotypist based in Milan, inviting him to come to London and to take portraits under a license. Vogel declined this invitation and, significantly, Henneman and his partner Thomas Malone were not to exploit the undoubted opportunity as visitors flocked to London.

Seemingly reticent to exhibit in person, in mid-February 1851 Thomas Malone prompted Talbot by sending him a list of Talbot’s negatives (in preference to positive prints) he would like to use for Henneman & Malone’s exhibits, adding “we shall feel obliged by your sending us anything that pleases yourself.” The official Reports by the Juries noted that “Mr. Talbot has, himself, exhibited nothing; but many of his productions will be recognized among those exhibited by Henneman and Malone.” Talbot did not receive an official prize for his exhibits, though he had the satisfaction of Henneman & Malone being awarded a Prize Medal. Having peeped through the windows of the Crystal Palace the day before, on the first day of May, 1851, Henry was one of those squeezed on the gallery at the south-west corner of the south transept for the official opening by Queen Victoria. Unfortunately, we have no record of his thoughts on his visits to the Exhibition or the photographs and photographic equipment on display.

The painful story of Henry’s unsuccessful attempts to secure photography and printing contracts for Henneman can be found primarily in the Talbot correspondence. These letters centred on the contract to supply photographs of prize winning exhibits for illustrations in the four-volume presentation set of the Reports by the Juries. Talbot claimed Henneman was contracted by the Executive Committee to supply 200 glass plate negatives at a cost of three guineas each, and 100 paper negatives, each costing two guineas. This agreement may have taken place as early as June 1851. Inexperienced in the production of the albumen on glass negatives, Henneman sub-contracted this part of his contract to the French photographers Friedrich or Frédéric von Martens (1806-1885) and the native Frenchman Claude Marie Ferrier (1811-1889). Talbot himself considered Martens “the best photographer in this line.” However, within only a few weeks, Martens became so frustrated by the bureaucracy he encountered when trying to photograph, he threw in the towel and headed back to Paris, leaving Ferrier to continue to photograph.

In parallel, the amateur photographer Hugh Owen (1808-1897), who worked for the Great Western Railway and was based in Bristol, had been approached by the Executive Committee to “make some experiments” began photographing inside the Crystal Palace. Owen was not the only amateur to photograph inside the Exhibition building, but he was to be the most significant since some of his photographs were eventually to be used to illustrate the Reports by the Juries. However, officials recorded that he was taking many more photographs for his own purposes. Some of which survive.

Talbot had already fallen out with an influential member of the Exhibition’s officials, Robert Ellis (1823-1885), who was to become the Scientific Editor of the Official Catalogue. In May 1850, Ellis had suggested to Talbot that as an amateur he be allowed to illustrate one of his books with a calotype without taking out a licence. Talbot thought otherwise. More significantly in the middle of July, Henry Cole noted in his diary that Prince Albert “has appointed Mr. Ellis on the subject of photographs.”

Perhaps a greater challenge than the taking of the negatives for the Reports, was their printing. Over 21,000 photographic prints needed to be individually printed and no photographic printer had ever attempted such a commission. Henneman began printing from the 100 paper negatives he had started taking and supplied prints from twenty of them for the inspection of the Executive Committee. These were rejected and Talbot sought a second opinion. He asked his friend David Brewster – who was Chair of Class X in which the majority of photographs were exhibited in the Crystal Palace – to examine Henneman’s prints and Brewster assured Talbot that “most of them were excellent, some most beautiful.”

However, a rare surviving example supports the Executive Committee’s contention that some of the images were too dark to be used. Henneman stated that the poor quality had been caused by their having been done in a hurry by one of his assistants while he was himself absent taking photographs at Osborne House, Isle of Wight for Queen Victoria. This rejection by the Executive Committee masked the negotiations that were taking place to find an alternative – cheaper – photographic printer.

In July Talbot headed off to Marienburg in Eastern Prussia to view the solar eclipse that took place on 28th July. While he was abroad, the Executive Committee began negotiations with Robert Jefferson Bingham (1825-1870), who, though he was part of the British photographic community, had no track record of large-scale photographic printing. Henry’s trip was then cut short when he received news of the death of his beloved half-sister Henrietta Gaisford, and this shock was to limit his visits to the Great Exhibition, and distract him from fully engaging with the Executive Committee and the Royal Commissioners.

In the meantime, Henneman had also not helped his or Talbot’s cause. At the end of July he had moved a statue of The Veiled Nymph, one of the statues by Rafaelle Monti (1818-1881), to a better position to photograph it, and had broken off some of the fingers in the process. Mr Tudor, the purchaser, now refused to take the statue. To rub salt into Monti’s wounds, he had entered Henneman’s establishment in Regent Street to find photographs of one of his statues in the Crystal Palace and, as The Times reported on Wednesday 30 July, “which had been taken entirely without his knowledge or permission; and he was still more surprised on learning that the counterproof had been carried off to Paris, where, by this time, his statue may be already pirated in clay or porcelain by some of those persons who are to be distinguished from artists as “art-manufacturers.” These issues were also discussed in the House of Commons.

On 20 August 1851 the Executive Committee wrote to Talbot informing him that they wished to use some of Owen’s photographs to illustrate the special copies of the Reports and that it wished to remunerate him for the “for the trouble he has taken & that he should be compensated for any impressions which he may furnish to the Commissioners.” The Executive Committee requested that Talbot waive his right to issuing a license “under the special circumstances.” A week later Talbot met Henry Cole who noted is his diary that Talbot “first agreed that Owen might be paid for his negatives if Henneman printed them, next that he must first take out a license & then be paid.” Who did finally print Owen’s negatives remains to be established.

Talbot was tenacious in his lobbying for Henneman. He secured support from two prominent and influential contemporaries to lobby on his behalf: David Brewster and Lyon Playfair, a Special Commissioner to the Exhibition. Talbot reported that Brewster spent two unsuccessful days in the third week of October seeking to meet with Colonel Sir William Reid (1791-1858), Chairman of the Executive Committee, to discuss why Henneman had not been awarded the printing contract and to “do justice to Henneman.”

Talbot was aware that the Executive Committee was in discussion with other parties regarding the photographic printing contract, but he was not sure who they might be. In early November he wrote to his licensee, George Knight and Sons, a photographic supplier, of Foster Lane, Cheapside in London, asking if he had signed such a contract. Talbot subsequently encouraged Knight to apply for the contract, and while Knight did meet with Henry Cole, Cole’s offer of only one shilling per print was deemed too low and Knight withdrew.

Henry persisted in promoting Henneman and suggested that the Dutchman could build a purpose-built printing production facility on the outskirts of London to undertake the contract. He even considered an ex parte injunction against Bingham. Perhaps the most intriguing meeting related to the printing of the glass negatives took place when Talbot met with Bingham. It is unclear where and when this meeting took place, but Talbot recorded that “I had an interview with Mr. Bingham himself when Mr. Bingham fully confirmed the statement” that he intended to sell “to the public [in France] for his own benefit as many copies [of prints from the glass negatives] as he pleased, after furnishing the stipulated number to the [Executive] Committee.”

Probably in mid-November Talbot came to the conclusion that he needed to agree a compromise. On 17th November, accompanied by his solicitor, John Henry Bolton (1795-1873), he went to the Crystal Palace and met with Henry Cole and Charles Wentworth Dilke of the Executive Committee, apparently the only two members of the Committee still at work. There they ironed out an agreement: “We have settled the matter with the Executive Committee – They are to be allowed to make the Copies of the pictures in the South of France, and in return are to give me fifteen Copies of the work, the value of which is roughly estimated at £30 per copy, or in the whole £450, and I am to make Henneman a present of £200 to compensate him for his trouble and disappointment.”

Henry continued to find reasons for the printing contract to be taken back from Bingham including his inexperience, a claim that he did not speak French, and the “political tumult” in France. Talbot even suggested that Bingham print the photographs “in the south of England, at some such place as Brighton for example.” However, by the end of the first week in December the glass negatives of Ferrier had been transported to France and arrived at Bingham’s newly established printing works in Versailles. The negatives were to spend almost two years in France before their return to London in August 1853.

Henry continued to promote his and Henneman’s cause and as in early December was suggesting that Henneman might be permitted to commercially sell prints from his paper negatives of the Exhibition. The Executive Committee stated the contract had been awarded to Bingham but “will be happy to try, in their individual capacities, to arrange between Mr Bingham and Mr Henneman.” Nothing came of this.

The sets of photographically-illustrated Reports by the Juries began to be distributed from February 1853. Talbot eventually received his fifteen copies in May 1853. He gave copies to some of his immediate family and to his old Cambridge college, Trinity. Having decided to print a presentation leaf for insertion into his gifts, he was remiss in distributing them and as late as August 1857 Harriot Mundy, his cousin and sister-in-law, wrote “I cannot resist reminding you of the ‘preliminary page’ or whatever it may be called which you promised us for the great Photographic Work.” In June 1860 Talbot’s wife Constance reported that there were still five copies at Lacock Abbey and that she had placed them “in a closet up the odd little ladder-stair by the housekeeper’s room door.” Their subsequent history remains unknown.

There were many lessons to be learned from the diverse aspects of photography at the Great Exhibition. Henry was scarred by the experience which was a catalyst for the events that led up to August 1852 when he partially relaxed his 1841 patent.

Some Octobers proved to be better than others for Henry.

Anthony Hamber

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Charles Burton. Aeronautical view of the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park from the South, lithograph. 1851, Victoria & Albert Museum, London. • Henry Cole, wood engraving after a daguerreotype by Antoine Claudet, Illustrated London News, 18 October 1851, p. 508. • Title page of volumes of the Reports by the Juries (London: printed by William Clowes and Sons, 1852), Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada. • Baron Gros, Interior of North Transept of the Crystal Palace, daguerreotype, 1851, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris; North Germany exhibit with Zolverein, from Dickinson’s comprehensive pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851 (London: Dickenson Bros, Her Majesty’s Publishers, 1852). • Nicolaas Henneman. Psyche Calling Love to her Aid, copy of a plaster by Charles Auguste Fraikin, salted paper print, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2888; Schaaf No. 4785. • Claude-Marie Ferrier, South Transept Exterior of The Crystal Palace; View of Eastern Nave, salted paper prints by Robert Bingham from Ferrier’s albumen on glass negatives; from volume 2 of Reports by the Juries. • Henry Talbot’s Presentation leaf for his copies of the Reports by the Juries. Dedicated in manuscript to his daughter Matilda, 1 January 1860; photograph courtesy of Bonhams, London.

![1851 Exhibition Folios Photography by Ed Bremner for Dr Anthony Hamber [#Beginning of Shooting Data Section] Nikon D3S 2014/08/07 14:18:18.65 Time Zone and Date: UTC, DST:ON Lossless Compressed RAW (14-bit) Image Size: L (4256 x 2832), FX Lens: Artist: Ed Bremner Copyright: Anthony Hamber Focal Length: 55mm Exposure Mode: Manual Metering: Spot Shutter Speed: 1/20s Aperture: f/16 Exposure Comp.: 0EV Exposure Tuning: ISO Sensitivity: ISO 200 Optimize Image: White Balance: Auto, 0, 0 Focus Mode: Manual AF-Area Mode: Single AF Fine Tune: OFF VR: Long Exposure NR: OFF High ISO NR: OFF Color Mode: Color Space: Adobe RGB Tone Comp.: Hue Adjustment: Saturation: Sharpening: Active D-Lighting: Normal Vignette Control: OFF Auto Distortion Control: Picture Control: [VI] VIVID Base: [VI] VIVID Quick Adjust: 0 Sharpening: 4 Contrast: Active D-Lighting Brightness: Active D-Lighting Saturation: 0 Hue: 0 Filter Effects: Toning: Map Datum: Image Authentication: OFF Dust Removal: [#End of Shooting Data Section]](http://foxtalbot.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/plates.jpg)