Snow is falling as I write here in Oxford, but that’s not the only thing falling hereabouts. Like the snow, as work continues on the catalogue raisonné the number of records with no image attached continues to drop. For that reason, we are grateful to all the Talbot owners who still send us images to represent their collections. This includes this week’s guest author, Madeleine Say, Pictures Collection Manager at the State Library Victoria, in Melbourne. In this week’s blog, Madeleine tells of the happy confluence that led to the formation of the largest collection of Talbot material in Australia.

Snow is falling as I write here in Oxford, but that’s not the only thing falling hereabouts. Like the snow, as work continues on the catalogue raisonné the number of records with no image attached continues to drop. For that reason, we are grateful to all the Talbot owners who still send us images to represent their collections. This includes this week’s guest author, Madeleine Say, Pictures Collection Manager at the State Library Victoria, in Melbourne. In this week’s blog, Madeleine tells of the happy confluence that led to the formation of the largest collection of Talbot material in Australia.

Previous blogs have highlighted the itinerant nature of Talbot’s work, which resulted in early photographs making their way to places as far flung as St. Petersburg. Now we travel even further, to Australia, where Madeleine perfectly illustrates the monumental task Professor Schaaf has faced ever since he began to systematically match photographic prints to their negatives almost fifty years ago. That task was on a global scale, but was no match for Larry’s determination to make as many connections as humanly possible. It is our hope that Larry and the catalogue raisonné will continue to generate photographic confluences, as they were in Melbourne, for many years to come.

Brian Liddy

Guest Post by Madeleine Say

Guest Post by Madeleine Say

Matilda Talbot’s stewardship material relating to Talbot material has been highlighted before in this blog. Her distribution of his photographs is well known, including the sets of her grandfather’s photographic experiments sent to ‘diverse institutions in places as far-flung as California, Canada and New Zealand’. It is from one of these gifts that the State Library Victoria, in Melbourne, now holds the largest collection of Talbot’s work in Australia.

How did the Library come to hold this collection? The answer is a combination of factors relating to our institutional history and fortuitous circumstance.

The Melbourne Public Library was established in 1854, on the same site as the now National Gallery of Victoria and the now Melbourne Museum. The history of the three institutions is intertwined. In this period there seems a degree of fluidity between who owned what and where unsolicited gifts were placed. The Gallery and Museum relocated to other sites in the 1960s and 1990s, leaving the Library as the sole institution in a complex of buildings which now occupies an entire city block.

It is interesting to reflect that when Matilda Talbot’s gift arrived in 1937 there was little fanfare or fuss. There is no mention of the donation in the institutional annual report. If such a gift was to arrive today the reaction would probably be very different. However in 1937, with the international situation deteriorating, the collection was placed in a brown paper envelope in the miscellaneous collection and stored away from light and damp.

The 1937 Miscellaneous Accession Register, recording ‘non book’ material added to the Library, has a one line entry noting the gift of 24 works from “Miss Talbot, Wiltshire England through Mr S C Richardson, Footscray”. Nothing is currently known about the connection between Miss Talbot and Mr Richardson, a company director for Richardson Gears Pty Ltd located in the industrial suburb of Footscray, or about Mr Richardson’s relationship with the Library.

Prof Larry Shaaf has written previously about Matilda Talbot’s gift to the Tartu University Library in Estonia. Like the Estonian collection the material sent to Melbourne contained examples of salted paper prints, photoglyphic engravings and photo-engravings.

Matilda Talbot’s intention was to promote her grandfather’s reputation, so the gift included a copy of the portrait by John Moffat showing Talbot with a camera. Someone has erroneously written on the back of the print “Fox Talbot’s self portrait”, and due to library catalogue rules it has to remain titled this way. A note in the record (which few read) attempts to give an explanation for this mistake.

During the 19th century Australians were greatly interested in the new science of ‘sun pictures’, and keenly followed developments. Sir Redmond Barry, first chairman of the Melbourne Public Library, recognised the ability of this new technology to record events and educate. Soon after the foundation of the library in 1856 he commissioned Barnett Johnstone to photograph the interior of the new Queens Reading Room, beginning a long tradition of collecting and commissioning photographs.

The library holds two copies of the 1846 Art Union Journal with the tipped in Talbotype still intact. The first was bought from London book dealer J. J. Guillaume in 1866, and second donated from the personal library of John Pascoe Fawkner, a Melbourne pioneer.

Matilda Talbot’s gift received little attention until the 1980s when the library established a separate Pictorial collection, and began cataloguing material in greater depth. This was perfect timing for the significance, and value, of the material to be recognised. A conundrum ensued: why the library could only account for 23 out of the 24 items listed in the original accession. A clue was written onto the brown paper envelope used to store the material; a pencil inscription said “(No 4 on loan to the Technological Museum 15/2/39)”.

We still have the original envelope on file, along with a series of spirited letters between the institutions requesting to know if the work, lent 50 years ago, could be located in the Museum collection.

This mystery was only solved when Professor Larry Schaaf visited Melbourne in 2011. His knowledge of Talbot’s work, along with his persistence and charm, enabled him to identify the work at Melbourne Museum. Given the work was borrowed for a Museum display the paper has suffered from UV exposure. But ever the optimist, Larry Schaaf said it proved Talbot’s point, as the borrowed item was one of his ink prints and more stable than a silver photographic image.

To date the Museum has not returned the work, but at least we know where it is, and more importantly what image completes the set in the original gift.

The library has only exhibited the works on one occasion. They were displayed in 1989, a year designated to mark 150th anniversary of photography. Even then events conspired to protect the material from environmental damage. The timing of the exhibition coincided with a power shutdown due to an electrical fault. The exhibition only opened to the public for two weeks. Despite this the arts critic Beatrice Faust described the exhibition as one of her ‘five star shows’ for that year.

The State Library’s small exquisite collection of William Henry Fox Talbots provided a unique blend of art and science, heavily freighted with the emotion that goes with epoch-making events. The authentic images of Talbot’s muslin, ferns and servants contained a shock of reality that was, for me, like looking at the Rosetta stone.

The purpose of Matilda Talbot’s gifts was to raise the profile of her grandfather’s achievements. The library collection remains a living example of her generosity, and subsequent interest in the material shows her wish has come to fruition.

Madeleine Say

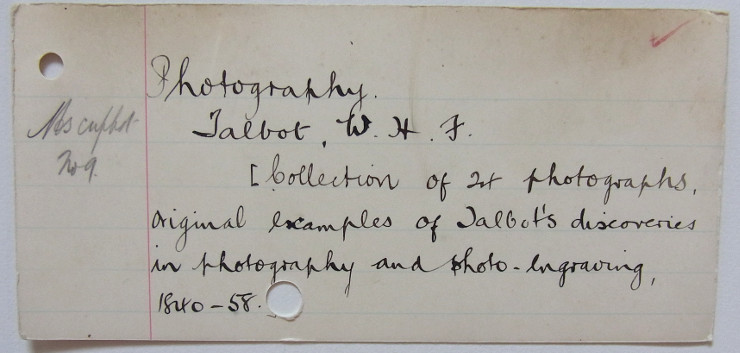

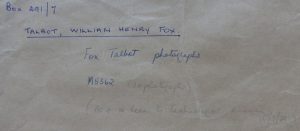

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Schaaf, L. J. (2000), The Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot, Princeton University Press: Princeton. p. 30. • Catalogue card from the Public Library catalogue recording the material and its location in Manuscript cupboard No 9. • Queen’s Reading Room, Melbourne Public Library, 1858 by Barnett Johnstone. Albumen silver photograph (H27161). The Chief Librarian and his assistants were roped in to pose. The photographer requested they sit ‘perfectly still for six minutes’. • Detail of the brown paper envelope used to store the collection for many years. • Faust, Beatrice (1990), ‘A year of garlic and Sapphires’, The Age 5 January 1990, p 10. • The entire collection can be seen via the libraries’ website catalogue: www.slv.vic.gov.au.

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Schaaf, L. J. (2000), The Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot, Princeton University Press: Princeton. p. 30. • Catalogue card from the Public Library catalogue recording the material and its location in Manuscript cupboard No 9. • Queen’s Reading Room, Melbourne Public Library, 1858 by Barnett Johnstone. Albumen silver photograph (H27161). The Chief Librarian and his assistants were roped in to pose. The photographer requested they sit ‘perfectly still for six minutes’. • Detail of the brown paper envelope used to store the collection for many years. • Faust, Beatrice (1990), ‘A year of garlic and Sapphires’, The Age 5 January 1990, p 10. • The entire collection can be seen via the libraries’ website catalogue: www.slv.vic.gov.au.