I hope that this past Tuesday you remembered to wish a happy birthday to Talbot’s friend, Sir John Herschel (7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871). When Herschel first learned of Talbot’s photography the scientific basis of it made so much sense to him that he perfected his own independent process in less than a week. Perhaps Sir John is best known today for his contribution of hypo as a ‘washing out agent’ (Talbot first used a fixer to stabilize his images and perversely over time the meanings of these two terms were inverted). On 1 March 1839, Talbot wrote to Françoise Biot about methods of making the photographic image permanent. After outlining his own approaches, Talbot enthused that Herschel’s “method … is alone worth all of the others together … wash the drawing with hyposulphite of soda. This technique must have presented itself quite naturally to Mr Herschel’s mind, since he himself discovered hyposulphurous acid, and noted its principal properties, among which he cites as particularly worthy of comment, that hyposulphite of soda easily dissolves chloride of silver (a substance which is ordinarily so little soluble).”

In early Roman calendars, before the introduction of the Julian, the Ides of March was determined by the first full moon of the new year. March was a strangely intermediary month for Talbot and only a few photographs can be positively dated to then. The winter weather would have been lifting, but unreliably, so in many ways the productions of this month were literally a warm-up act for April.

March 1839

The early part of 1839 was complex and busy for Henry Talbot. Our attention to Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre’s surprise announcement at the beginning of January sometimes overshadows our perception of Talbot’s fuller life. He had to prepare a hasty exhibition of photographs for the Royal Institution, then deliver his first paper on photography before the Royal Society and then disclose the working details of his process by mid-February. But along with this photographic activity, Talbot was busy in other areas of interest. He published two concise books just at the time of the introduction of photography.

The early part of 1839 was complex and busy for Henry Talbot. Our attention to Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre’s surprise announcement at the beginning of January sometimes overshadows our perception of Talbot’s fuller life. He had to prepare a hasty exhibition of photographs for the Royal Institution, then deliver his first paper on photography before the Royal Society and then disclose the working details of his process by mid-February. But along with this photographic activity, Talbot was busy in other areas of interest. He published two concise books just at the time of the introduction of photography.

Grass, photogenic drawing negative, 6 March 1839

Grass, photogenic drawing negative, 6 March 1839

The weather was truly awful throughout 1839 and this hurt Talbot especially in the earlier part of the year. The basic currency of his photographs – light – was in terribly short supply, but no less so than his stock of examples to display and distribute. Camera images were all but impossible for the first half of the year and even photograms were difficult to make much of the time. I suspect that this oddly-shaped negative was trimmed for display, but as we have seen before, Talbot’s shearers seemed to follow their own compass.

Arguing against exhibition, this particular negative is richly annotated on the verso. The ’10’ in the lower part probably indicates the exposure time, more likely ten minutes than ten seconds. The ‘fx’ of course is an indication of fixing and the date is clear. Subject to the analysis of Mike Ware’s acolytes, the ‘W./S. Salt/W/’ is probably the method of fixing: wash / put in a solution of saturated table salt / wash again, a good practice and one that has defended this fragile image now for 178 years. Were these annotations strictly for Talbot’s personal research notes? Or did he record them in order to demonstrate to others the advancing nature of his process?

Arguing against exhibition, this particular negative is richly annotated on the verso. The ’10’ in the lower part probably indicates the exposure time, more likely ten minutes than ten seconds. The ‘fx’ of course is an indication of fixing and the date is clear. Subject to the analysis of Mike Ware’s acolytes, the ‘W./S. Salt/W/’ is probably the method of fixing: wash / put in a solution of saturated table salt / wash again, a good practice and one that has defended this fragile image now for 178 years. Were these annotations strictly for Talbot’s personal research notes? Or did he record them in order to demonstrate to others the advancing nature of his process?

March 1840

Hyacinths, pottery, a shell and a candlestick, 1 March 1840

Hyacinths, pottery, a shell and a candlestick, 1 March 1840

In the second public year of photography Talbot’s spirits were buoyed by much improved weather. He was still limited by his original photogenic drawing process, both for photograms and camera negatives, but his mastery of the process had evolved so much that he was beginning to produce beautiful full plate negatives. We have seen what he was able to display to the members of the Graphic Society by May 1840, but even before then his visual strength was beginning to grow.

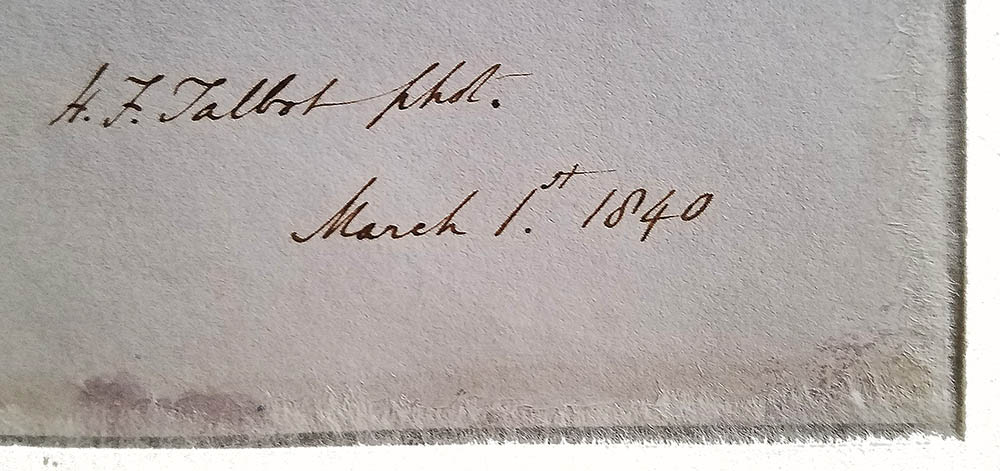

Talbot sent this print to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris and proudly signed and dated it on verso. On the question of ‘Talbot’ versus ‘Fox Talbot’, we are reminded by this that so far in no example of a signed print or negative did Henry spell out his middle name of Fox.

Talbot sent this print to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris and proudly signed and dated it on verso. On the question of ‘Talbot’ versus ‘Fox Talbot’, we are reminded by this that so far in no example of a signed print or negative did Henry spell out his middle name of Fox.

March 1841

Henneman Chopping Wood at Lacock Abbey, 16 March 1841

Henneman Chopping Wood at Lacock Abbey, 16 March 1841

Circumstances had changed radically for Talbot by March 1841. The previous September, he had discovered what would become known as the calotype process. Recognizing that an invisible latent image was created with very little exposure to light and that this could be amplified through the use of a chemical developer, Talbot saw his exposure times plummet from tens of minutes to a few seconds. Photogenic drawing was already well on the way to teaching him how to see, and Henry responded to increasingly difficult and sophisticated subjects. He was able to depict in exacting detail his servant carrying out an ordinary day to day activity on the estate. The slant of the sunlight brings out the fine details of the boards and twigs. Henneman has casually hung his jacket on the boards, stripped down to his waistcoat for the vigorous swing of the axe. We have already seen his famous Woodcutters, made perhaps a year or two later, and while it is a great photograph I actually prefer this earlier one. The Woodcutters is obviously staged and while it depicts a certain kind of truth, the present example rings of authenticity. Is this one the work of a developing artist who has yet to pay full attention to the feedback of his viewers? In the conventions of wood engravings and lithographs of the period, the staged quality of The Woodcutters is to be expected and perhaps Talbot’s audiences began to encourage him more towards conventionality. Had the present depiction of Henneman been shot with a Leica on Tri-X – oh, sorry, on a recent iPhone – that would not surprise us. It is reality recorded realistically.

But Talbot obviously intended this photograph to be seen by others. As is characteristic of this period, he has carefully inscribed the date in a thin area of the negative so that it would show through in the print, in this case in the lower right corner. This print was made before Talbot additionally annotated the negative, revealing that this very life-like pose was held for a two minute exposure.

But Talbot obviously intended this photograph to be seen by others. As is characteristic of this period, he has carefully inscribed the date in a thin area of the negative so that it would show through in the print, in this case in the lower right corner. This print was made before Talbot additionally annotated the negative, revealing that this very life-like pose was held for a two minute exposure.

March 1842

The Bell Tower at Bowood, 15 March 1842

The Bell Tower at Bowood, 15 March 1842

Bowood House, near Calne in Wiltshire, was about 5 miles North East of Lacock. Henry was intimately familiar with this nearby grand house, for it was the seat of his uncle, the Marquess of Lansdowne, and a haunt familiar from childhood. By 1842 it was natural for him to take his camera to record such a site.

Upon looking at his negative for the Entrance Gateway at Queen’s College, Oxford, Talbot was taken by surprise. As he wrote in his text for this image in The Pencil of Nature, “in examining photographic pictures of a certain degree of perfection, the use of a large lens is recommended, such as elderly persons frequently employ in reading. This…often discloses a multitude of minute details, which were previously unobserved and unsuspected. It frequently happens, moreover—and this is one of the charms of photography—that the operator himself discovers on examination, perhaps long afterwards, that he has depicted many things he had no notion of at the time. Sometimes inscriptions and dates are found upon the buildings, or printed placards most irrelevant, are discovered upon their walls: sometimes a distant dial-plate is seen, and upon it—unconsciously recorded—the hour of the day at which the view was taken.”

Upon looking at his negative for the Entrance Gateway at Queen’s College, Oxford, Talbot was taken by surprise. As he wrote in his text for this image in The Pencil of Nature, “in examining photographic pictures of a certain degree of perfection, the use of a large lens is recommended, such as elderly persons frequently employ in reading. This…often discloses a multitude of minute details, which were previously unobserved and unsuspected. It frequently happens, moreover—and this is one of the charms of photography—that the operator himself discovers on examination, perhaps long afterwards, that he has depicted many things he had no notion of at the time. Sometimes inscriptions and dates are found upon the buildings, or printed placards most irrelevant, are discovered upon their walls: sometimes a distant dial-plate is seen, and upon it—unconsciously recorded—the hour of the day at which the view was taken.”

March 1843

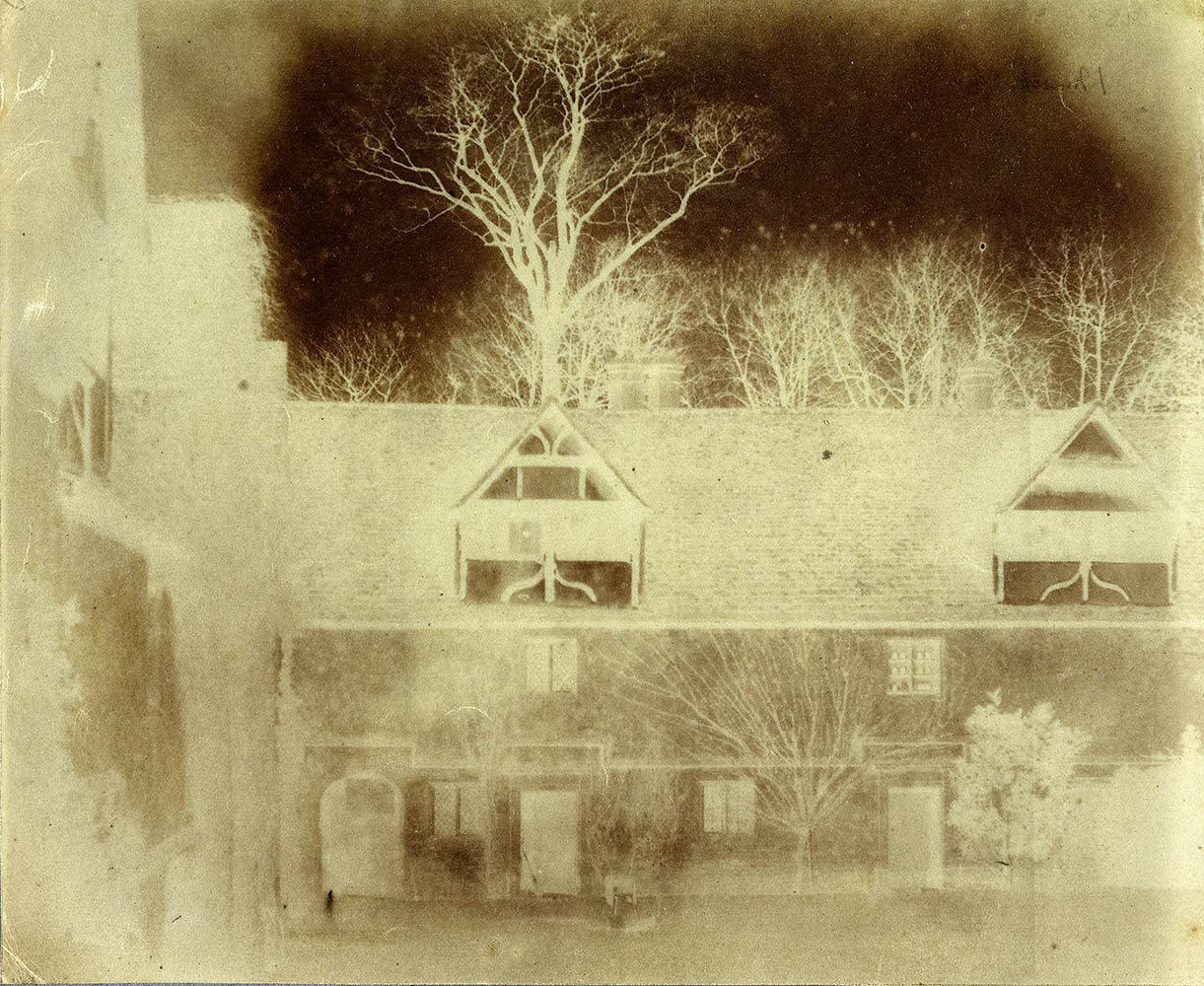

The Stable Block in the North Courtyard of Lacock Abbey, 1 March 1843

The Stable Block in the North Courtyard of Lacock Abbey, 1 March 1843

By 1843 Talbot’s technique and his mastery of his craft had fully matured. We don’t even need the dating of this photograph to observe the bare winter trees and to realize that the light would be weak. I don’t know how long his exposure time was here and for this type of photograph it doesn’t matter so much. However, in order to get the sharply defined details it had to be relatively short. With photogenic drawing, not only would the wind disturb a half hour or so exposure, but also the angle of the shadows would change with the rotation of the earth, confusing the outlines. With the calotype negative process, an exposure of two or three minutes would suffice, freezing all the fine lines.

We have seen this before but I can’t resist pointing it out again. Both the above negative and the one for a rendition of The Soliloquy of the Broom are dated the same day. Examine the center left rectangular doorway in the negative and you will see a broom propped up in front of Talbot’s dark cloth covered camera, a rare record of the making of a piece of art. It is the sort of little detail, often unnoticed at first, which brings delight in closely examining Talbot’s photographs.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Alfred E. Chalon, John Herschel, miniature painting, 1829; courtesy of John Herschel-Shorland. • Since part of the point of these blogs is to look at the photographs as Talbot and his peers would have seen them, some of the reproductions in the blog have been gently digitally enhanced for clarity, all the time avoiding taking them beyond what I imagine they were like originally. The entries in the Catalogue Raisonné proper always represent the current state of the originals as closely as possible. • WHFT to Biot (translated from the original French), Talbot Correspondence Project Document no. 03827. • WHFT, Grass, photogenic drawing negative, 6 March 1839, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1995.206.36, Schaaf 1508. • There are no entries in Talbot’s research notebook for 6 March but the context around this date can be surmised from my Records of the Dawn of Photography: Talbot’s Notebooks P & Q (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). • WHFT, Hyacinths, pottery, a shell and a candlestick, salted paper print from a photogenic drawing negative, 1 March 1840, Académie des Beaux-Arts, Paris, 5.e.29 (1840) f 11; Schaaf 3687. • WHFT, Henneman Chopping Wood at Lacock Abbey, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 16 March 1841, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-366/6; Schaaf 2567. • WHFT, The Bell Tower at Bowood, calotype negative and digital print, 15 March 1843, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1576; Schaaf 2630. • WHFT, The Stable Block in the North Courtyard of Lacock Abbey, calotype negative, 1 March 1843, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1532; Schaaf 2711. • WHFT, The Soliloquy of the Broom, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 1 March 1843, the Art Institute of Chicago, 1972.345; Schaaf 2712.