This has been a fruitful summer for photographic exhibitions. Not so much for the blockbuster kind that will provide fodder for hopeful art historians in the coming years, but more for ones that are important in that they dare to approach familiar subjects with solid grounding, a refreshing take and a bit of flare. I’ve just returned from seeing three such exhibitions, very different in character, and I am delighted to have had the privilege. And two of them are still up for a while – I would encourage you to get to them if you can.

This has been a fruitful summer for photographic exhibitions. Not so much for the blockbuster kind that will provide fodder for hopeful art historians in the coming years, but more for ones that are important in that they dare to approach familiar subjects with solid grounding, a refreshing take and a bit of flare. I’ve just returned from seeing three such exhibitions, very different in character, and I am delighted to have had the privilege. And two of them are still up for a while – I would encourage you to get to them if you can.

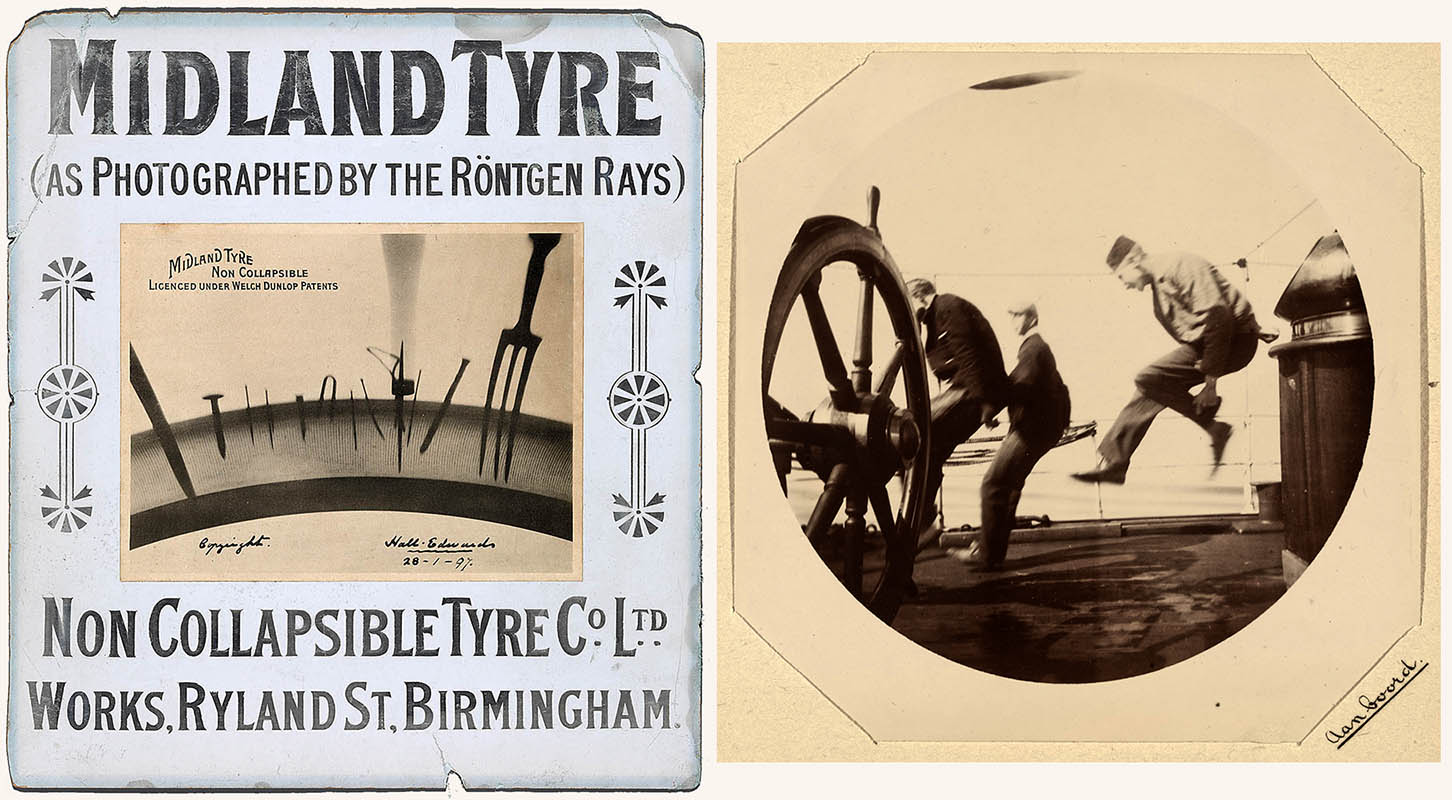

From there, ranged over several galleries, the thematically organised exhibition explores various facets of photography, including ‘Early Days’, ‘Metal and Ink’, ‘Advertising’ and ‘New Directions’. That probably sounds a bit old school to some aficionados, but the sheer volume, the quality of the selection and the quality of the display all work together to make this a special experience. (If I am required to have a connection to Henry Talbot in this blog, this exhibition is a vivid demonstration of the consequences of his active imagination.)

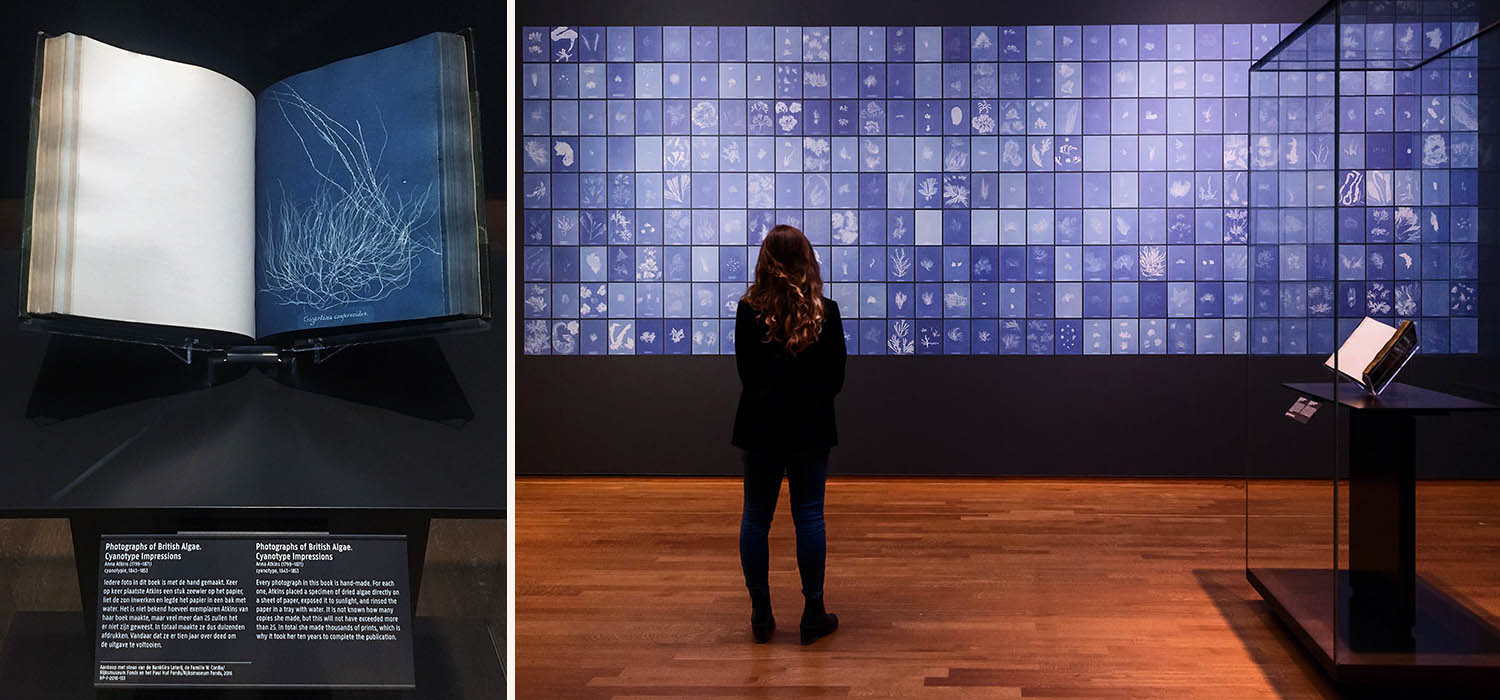

The spare setting of the Atkins is successfully carried throughout this exhibition, wisely re-purposing cases drawn from elsewhere in the museum.

One will find great art in here, and that is to be lauded, but I think more importantly one is reminded of the many facets of photography – just how versatile and pervasive a tool it has proven to be over the years in many hands.

The exhibition runs until 17 September and I encourage you to see it in person if you possibly can. Whether you are able to or not, the substantial catalogue is real treat (although defiant of the confines of my desktop scanner). The principal authors are curators Mattie Boom and Hans Rosemblum, supported by essays from Saskia Asser (a descendant of the pioneering Dutch photographer, Eduard Isaac Asser, who is represented in the show), our own bon-vivant and collector, Steven F. Joseph, whose perceptive eye secured many of the contributions shown, and the Rijksmuseum’s Martin Jürgens, one of the coterie of conservators emerging as the true photo-historians of our age.

(the paperweight is my own and is not included with the catalogue)

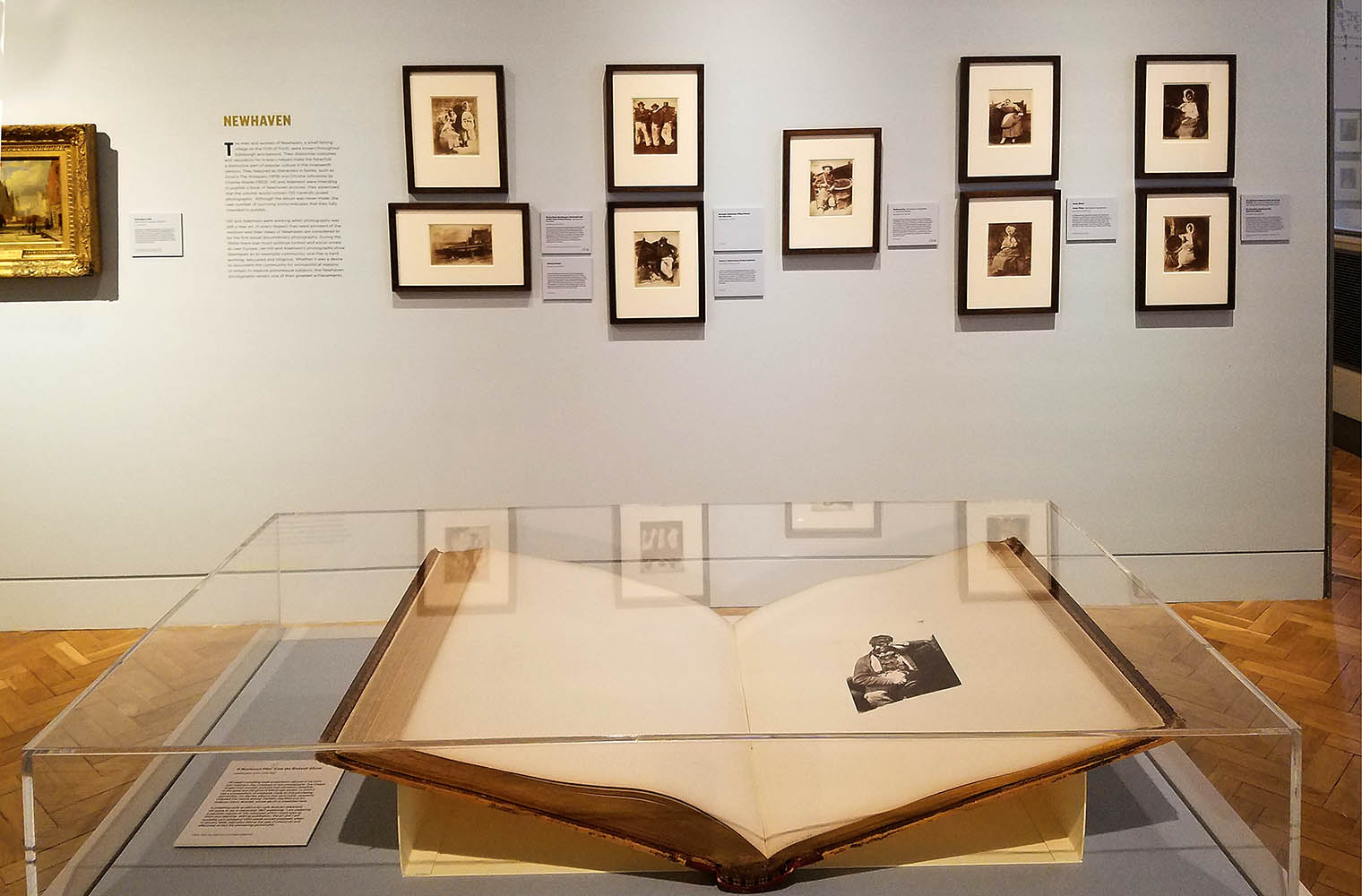

Moving on to the Auld Reekie, the Athens of the North, I fortunately managed to get to my old base of Edinburgh just ahead of the Festival crowds in order to see A Perfect Chemistry. It was. Through the long-standing work of Sarah Stevenson, David Bruce and others before them, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery is inextricably linked to the extraordinary partnership of Robert Adamson and David Octavius Hill. They were freely encouraged by Henry Talbot, especially through the mutual contact of Sir David Brewster, to practise the calotype and the result was a massive and singular output of photographs unlike any other in the early history of the art. I was surprised that it has been fifteen years since the last exclusive showing of Hill & Adamson in these galleries, so in any case it was time for new generations to be inspired. The J Paul Getty Museum lost a treasure four years ago when Annie Lyden returned to her native land to pick up where Sara left off and she has managed to successfully retain the previous scholarship while advancing into new interpretations of familiar pieces.

The exhibition starts off with the most splendid display of Hill’s 1866 painting, The Signing of the Deed of Demission, the impetus for his taking up with Adamson and the result of two decades of struggle attempting to reduce the calotypes to a mere painting. This hideous/hilarious canvas was shown in London in 1867, then for many years hung in the offices of the Free Church of Scotland overlooking the New Town. I saw it at the Tate last year, where it was perched awkwardly low in a cavernous room, but really appreciated it for the first time last week in a spot-on display. The Free Church officials were always accommodating, but the cramped room and unhappy lighting of their office reminded me of struggling to view paintings in Italian churches decades ago. I couldn’t help digging out my old Ektacolor snapshot from August 1983. Sara Stevenson’s long locks introduce us the left side, Nigel Thorp brightens the centre, is that Ray MacKenzie and pre-Dr Alison Morrison-Low in the foreground? the indomitably enthusiastic David Bruce guides us through the viewing and Mark Haworth-Booth impishly anchors the right.

With its smoke-encrusted glass removed and the painting hung in its original frame and properly lit, close viewing is demanded. You’ve probably already seen the details of Hill intensely sketching on the lower left and Adamson manipulating his camera at the top. The Free Church became very active in establishing foreign missions, and the international nature of the attendance along with the educational allegories is probably rarely considered and is something that the ability to have a lingering look at the elements of the painting encourages. A brilliant move on Annie’s part is to relate the disruptive nature of The Disruption to the disruptive events of our day. The divisive nature of Brexit and the DT come out in her narrative, particularly in the audio guide where her informed informality skillfully navigates the tricky political shoals.

Only in recent years has proper recognition of the negative been emerging, albeit slowly, and several original calotype negatives are on display. In contrast to past emphasis, Annie embraces Hill’s handwork on the negatives – a retouching that was anathema to Henry Talbot but comfortable, indeed to be expected, of an accomplished artist like Hill, especially in reference to his engravings. Here we see the Rev. Dr James Julius Wood of Greyfriars’ Church, Edinburgh, who was the Moderator of the Free Church Assembly. The over/under hanging of the negative and its print encourages viewers to examine what Hill felt compelled to supplement or ‘correct’. That is an opportunity that few non-photohistorians have ever had or have ever even thought about. There is a clear explanation of the difference between the developed calotype negatives and the salted paper prints made from them, a distinction still misunderstood in some scholarly and many popular texts.

For me, some of Adamson & Hill’s most interesting photographs have always been those of the built environment. In a print from one of their larger negatives taken on 9 September 1844, we see the construction of Free St John’s, the new Assembly Hall for the Free Church, designed in the Gothic style by Augustus Pugin and James Gillespie Graham. Its octagonal spire, rising 74 meters (240 feet) is the tallest in Edinburgh. After the Free Church merged back into the Church of Scotland, it was for a time St Columba’s – the building now lingers on as the unsympathetically-named ‘Hub’, a central point for the Edinburgh Festival. The negative for this print is one of sixteen negatives of the church in various stages of construction in Special Collections of the Glasgow University Library.

Many of the Hill & Adamson prints that we know are contained in splendid presentation albums compiled by Hill after his partner’s tragic early death. One of the seminal influences on me in the late 1960s was the magnificent Clarkson Stanfield album at The University of Texas (it was the major reason that Helmut Gernsheim backed away from Anna Atkins, but that is a story for another day). These very rare albums not only contain typically one-hundred splendid prints, but they are critical testimony to the networks of artists that embraced the calotype. One such album is displayed in this exhibition, compiled by Hill for the art collector Henry Sanford Bicknell (1818-1880), the greatest patron of the painter J.M.W. Turner. His father amassed his wealth as a sperm oil merchant, lighting up Britain’s lighthouses, a critical industry for a maritime nation. In 1862, his brother Herman became the first foreigner to visit Mecca wholly undisguised. Henry became a Director of the Crystal Palace Company and married the only daughter of the Scottish painter David Roberts. One can only imagine all the important people who viewed this album over the years. Generously loaned to the exhibition by a private owner, it is well displayed against a backdrop of prints similar to those it contains.

The exhibition runs through the first of October so hopefully you will get a chance to see it. There is a modest catalogue to accompany it, perfectly fine and well produced, but of course unable to reproduce the visceral experience of seeing the originals. It should be on your bookshelf but don’t make the mistake of judging the boundaries of the exhibition by the more limited nature of its catalogue.

![]()

For the final leg of my journey, I was met in Birmingham by our contributor, Pete James, the former Curator of Photographs for the Library of Birmingham (whose position was collateral damage from the construction of a truly extraordinary new building). I’ve previously covered my reaction to Mat Collishaw’s augmented virtual reality exhibition, Thresholds, which is based on Talbot’s August 1839 major exhibition before the British Association for the Advancement of Science, held in Birmingham almost 178 years to the day before I turned up at the actual site. Although the impact was slightly lessened by a third viewing, it is still quite eerie to enter a plywood box to suddenly find yourself in a gaslit room, moths circling, replete with 1839 Talbot images, mice scurrying about the floor and the chants of Chartists in the streets outside.

What made the Birmingham showing of this special was Pete’s fabulously detailed research, pointing out the original location and finding surviving drawings and models of the venue for Talbot’s critical exhibition. It was a rich experience, sadly just finishing its run while I was there.

There were other good things to see. Right in the same room as the plywood box was a small display of Cornelia Parker’s Articles of Glass, a homage to Talbot’s photographs under that title but now expressed in polymer photogravures (a descendant of Talbot’s photoglyphic engravings). The original glassware was borrowed from the Bodleian’s Fox Talbot Archive – glass that had witnessed Talbot’s sunbeams and now Parker’s UV light.

I saw one more extraordinary thing in Birmingham that day. Pete’s discovery – was it 25 or so years ago? – of one of only two surviving Wolcott cameras provided the impetus for A White House on Paradise Street, a collaboration between the artist Jo Gane, Pete and digital artist Leon Trimble. The first daguerreotype in Birmingham was a now-lost 1839 one of a white house on Paradise Street made by the local scientist, artist, lecturer and patent agent, George Shaw. Pete has promised a guest blog soon on this little-known but fascinating figure.

Cabinetmaker Jamie Hubbard re-created the mahogany daguerreotype camera, the most advanced such instrument of its (early) day, now fitted out with a back not of silvered copper but rather with a sensor connected to a Raspberry Pi micro-computer. An interesting idea.

Although you will have missed Thresholds at its natural home of Birmingham, it is being re-constructed as we speak at a different sort of natural home, Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire. I hope to see it there and certainly encourage you to do so – it runs from 16 September to 29 October.

.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Actually, this is a Talbot blog lacking any Talbots to credit. • Many thanks to Mattie Boom, Annie Lyden and Pete James for their generosity with their time and some stimulating conversations in and around their exhibitions. (And for supplying some of the snapshots.)