guest post by Brian Liddy

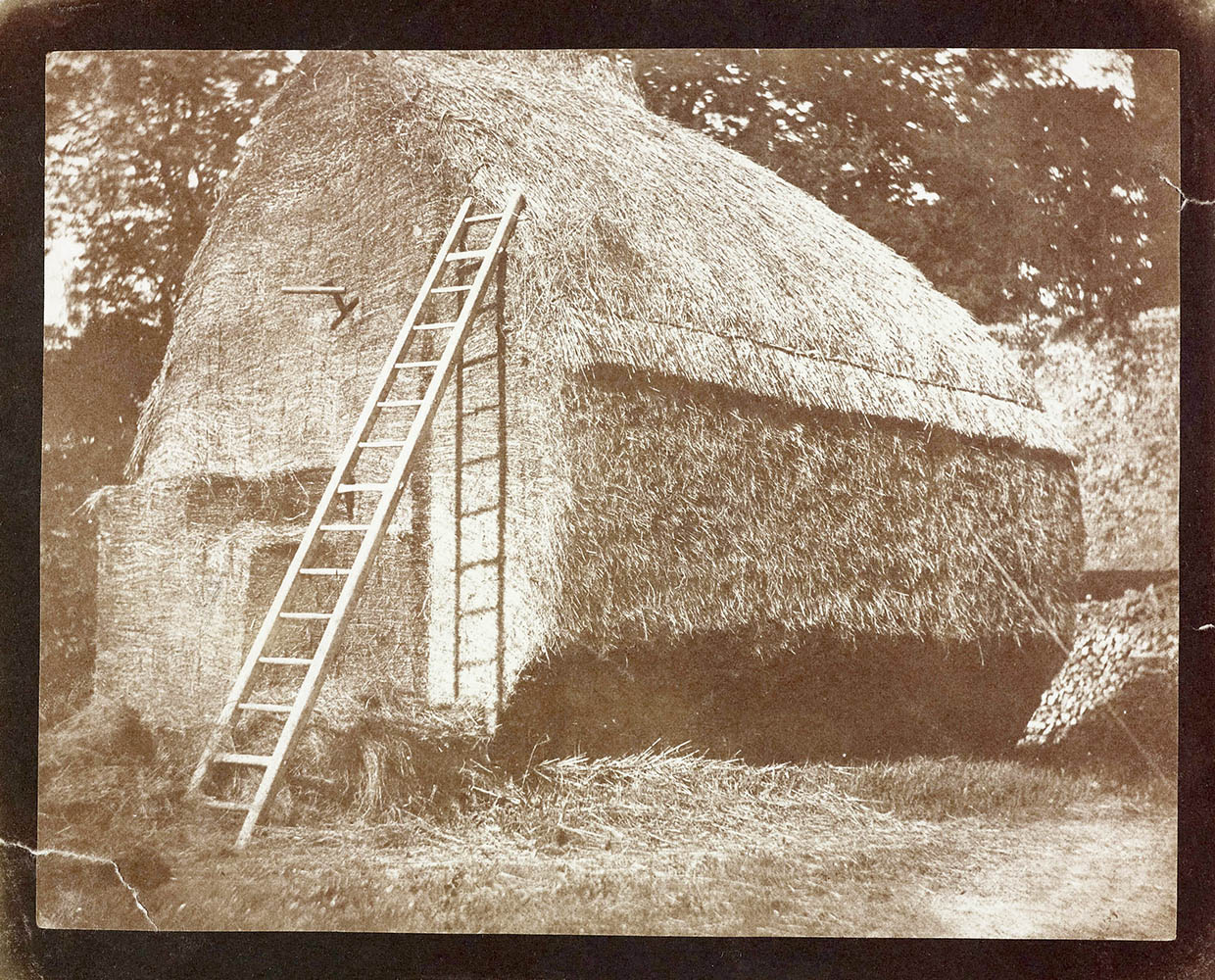

Of all the seasons autumn is my favourite. As the days shorten, summer transitions to winter. Leaves turn and conkers appear on roadsides and earthy whiffs rise after late summer showers. Meanwhile geese take arrow formations across the sky and the air noticeably chills as the sun sets earlier every day. Autumn is just around the corner. Even this city boy is aware, as he travels through the countryside that fields recently ripe with mature crops are now shorn and reduced to stubble. I’m reminded of one of Talbot’s most successful compositions, “The Haystack”.

I like this particular print, for in spite of its tears, it clearly shows what Talbot saw in this image. In our mechanised world these hand-made stacks have been replaced by more efficient bales, but seeing them reminds me of current news stories regarding the possibility that crops will be left to rot in fields in a post-Brexit Britain (something I’m told is already happening across the pond in what seems a sudden and irrational anti-immigrant America).

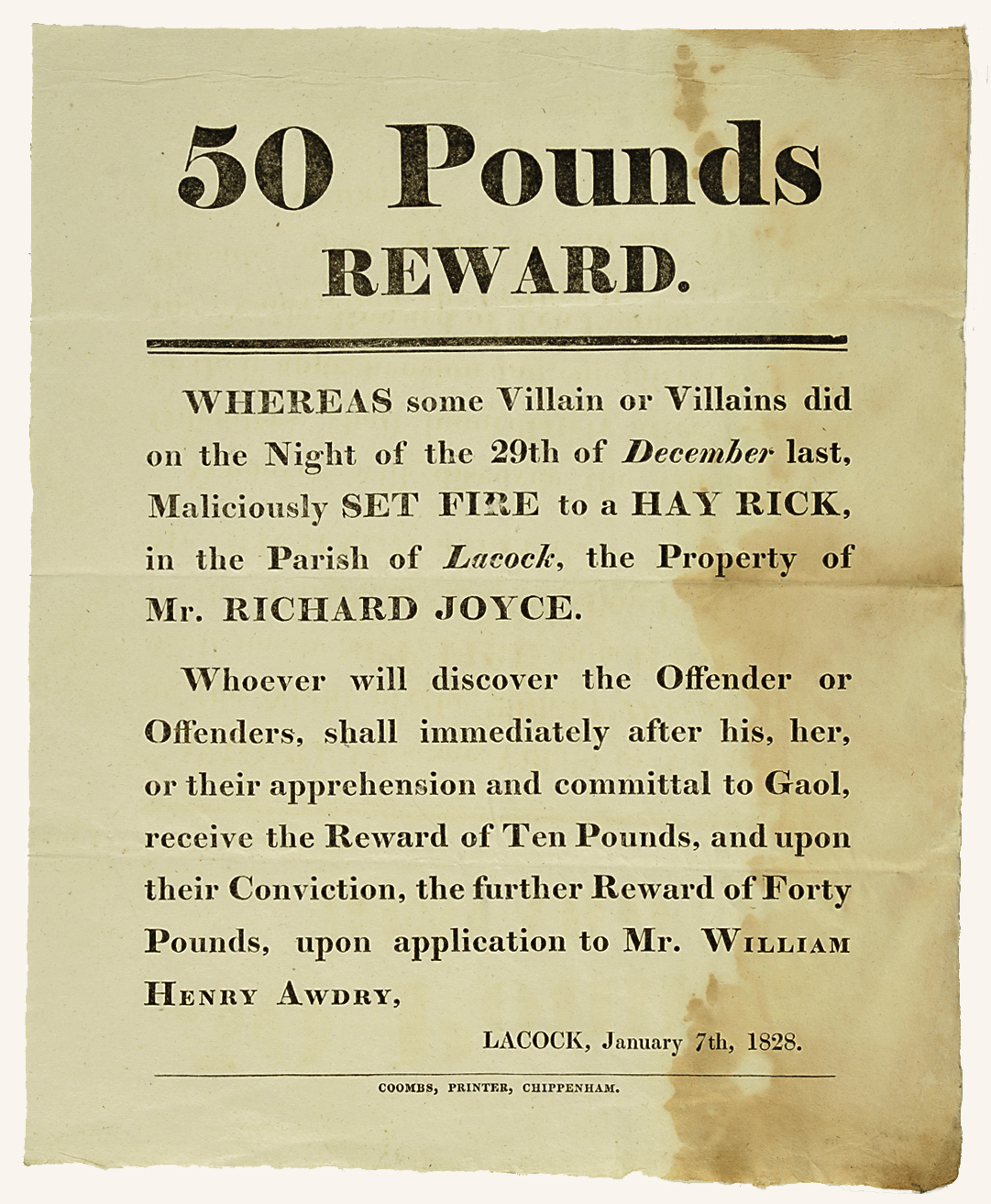

However, in Talbot’s day, haystacks, otherwise known as hay ricks, were constant reminders of the Swing Riots that raged through the English countryside of the 1830s. As a compassionate landowner, Talbot must have been torn by the political strife, as haystacks were burned by displaced, angry farmhands robbed of hope. During the riots, nearly a hundred threshing machines were destroyed, while twenty hayricks and at least one cottage was burnt down. Luckily, Lacock escaped unscathed.

By 1844 the Riots began to fade into memory, but perhaps Henry recalled them in including ‘The Haystack’ in The Pencil of Nature. Its text is among the briefest in the entire publication, but the observations that Talbot makes are strong ones:

One advantage of the discovery of the Photographic Art will be, that it will enable us to introduce into our pictures a multitude of minute details which add to the truth and reality of the representation, but which no artist would take the trouble to copy faithfully from nature. Contenting himself with a general effect, he would probably deem it beneath his genius to copy every accident of light and shade; nor could he do so indeed, without a disproportionate expenditure of time and trouble, which might be otherwise much better employed. Nevertheless, it is well to have the means at our disposal of introducing these minutiae without any additional trouble, for they will sometimes be found to give an air of variety beyond expectation to the scene represented.

In three sentences Talbot observes that an artist working in a traditional manner couldn’t and wouldn’t take the time and trouble to illustrate every single straw in the haystack. Yet, photography could do that with ease. Even artists belonging to that Victorian equivalent of the photorealist school, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, would not claim to literally portray every leaf of every tree, or every hair of a human head, never mind the innumerable straws protruding from the surface of a haystack. In that sense, Talbot’s negative is a tour de force. Surprisingly un-waxed, his paper negative demonstrates the very best his calotype process could achieve.

We associate haystacks with an autumn harvest, but Talbot’s haystack was photographed in the spring towards the end of its life. It may not be obvious but the stack, when complete, would have been longer than we see it now. Sections have been cut away to provide feed for livestock and steps with a platform for the farmhand to work from has been expertly carved out of the hay. Everything about this stack of hay is ingenious. A hay-knife (really a coarse tooth saw) was designed to saw off sections at the end of the bale, but here it marks where the last person to use it stood to cut hay from the stack. The knife was then thrust into the newly exposed hay so that it was always to hand and ready for use.

‘The Haystack’ is such a powerful image that it has often been seen as an allegory. As an expression of national identity, one only has to look to French variants painted by Monet. As a study of geometry, angles, volumes and space, it might reflect Talbot’s interest in mathematics or science. The angles generated by the stack’s geometric form are enhanced by the shadows cast by the ladder and the hay-knife thrust into the side of the stack. As makeshift sundials they imply the passage of time. Or, on a cosmic scale, they signal our place in the solar system. But on a more prosaic level perhaps Talbot had to ask the person who had thrust the hay-knife into the stack to step aside for a moment so that the picture could be taken?

At the risk of reading too much into the image, I’d probably go so far as to say that there is a political element to the composition. The more I look at Talbot’s haystack the more I’m struck by its solid construction and the care with which it was built. Its design is the result of hundreds of years of accumulated experience, gathered since the agrarian revolution of the Middle Ages. Everything about the stack is there for a reason and is designed to aid the survival of hay through the winter so that it can be used as a source of nutrition for grazing livestock, to sustain them through the lean winter months. My first thought regarding the deeper meaning of Talbot’s haystack is somewhat eschatological (apologies, as eschatology is the study of end things). This could be the end of anything, an individual life, to that of an era, but perhaps it is most to do with the end of all things. In other words, the end of the world, or Judgement Day. I realise it may seem far-fetched to say that Talbot’s haystack is an allegory of Heaven, but the presence of the ladder only fuels that notion in my mind with its association of ascension.

There are several Talbot photographs incorporating haystacks, usually in context as a prop in a portrait. Each has its own appeal, but none are quite so evocative as the one Talbot chose for, The Pencil. But there is one that does not neatly fit the pattern.

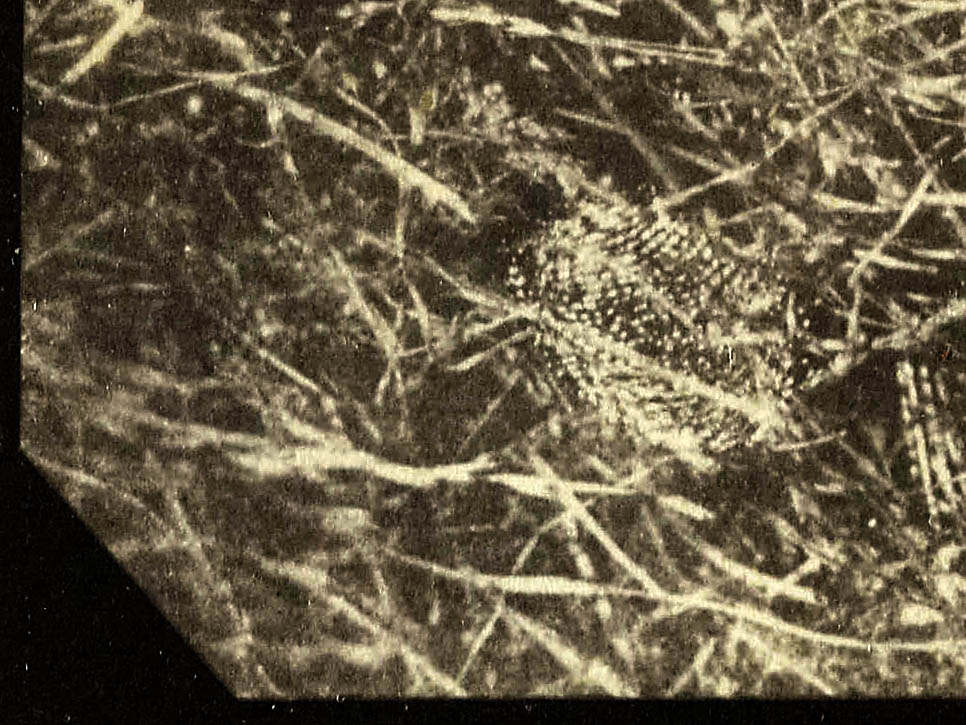

Here, has Talbot literally made the central subject of the photograph the individual straws of hay trapped within the haystack? What prompted him to undertake this remarkable study of grasses? Was it the sheer delight of an abstract rendition free from the artist’s pencil? Could this close-up image be a detailed response to the mirror-like verisimilitude of the daguerreotype? ‘The Haystack’ was already a success in conveying such detail, so what compelled him to move in so close? Perhaps we are making a false association here. In contrast to the orderly construction of ‘The Haystack’, this is an image of randomly scattered grasses. Perhaps they are the bent leftover stalks from an empty autumnal field. Perhaps they lie where and how they have been cut, ready to find themselves incorporated into the art of the hayrick builder. If you load any one of our handsome haystack photographs onto the website’s Image Viewer you can zoom in to see the fine layers or striations of hay, compressed since the previous autumn harvest.

Brian Liddy

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, The Haystack, salted paper print from a calotype negative, April 1844, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1251/1, Schaaf 2770. • Broadside, 50 Pounds Reward, Lacock, 7 January 1828, Fox Talbot Archive, the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, FT10489. • WHFT, Hayrick and Woodshed, Lacock Abbey, calotype negative and digitally-derived print, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2632, Schaaf 2174. • WHFT, Study of Grasses, salt print from a calotype negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, Schaaf 933.