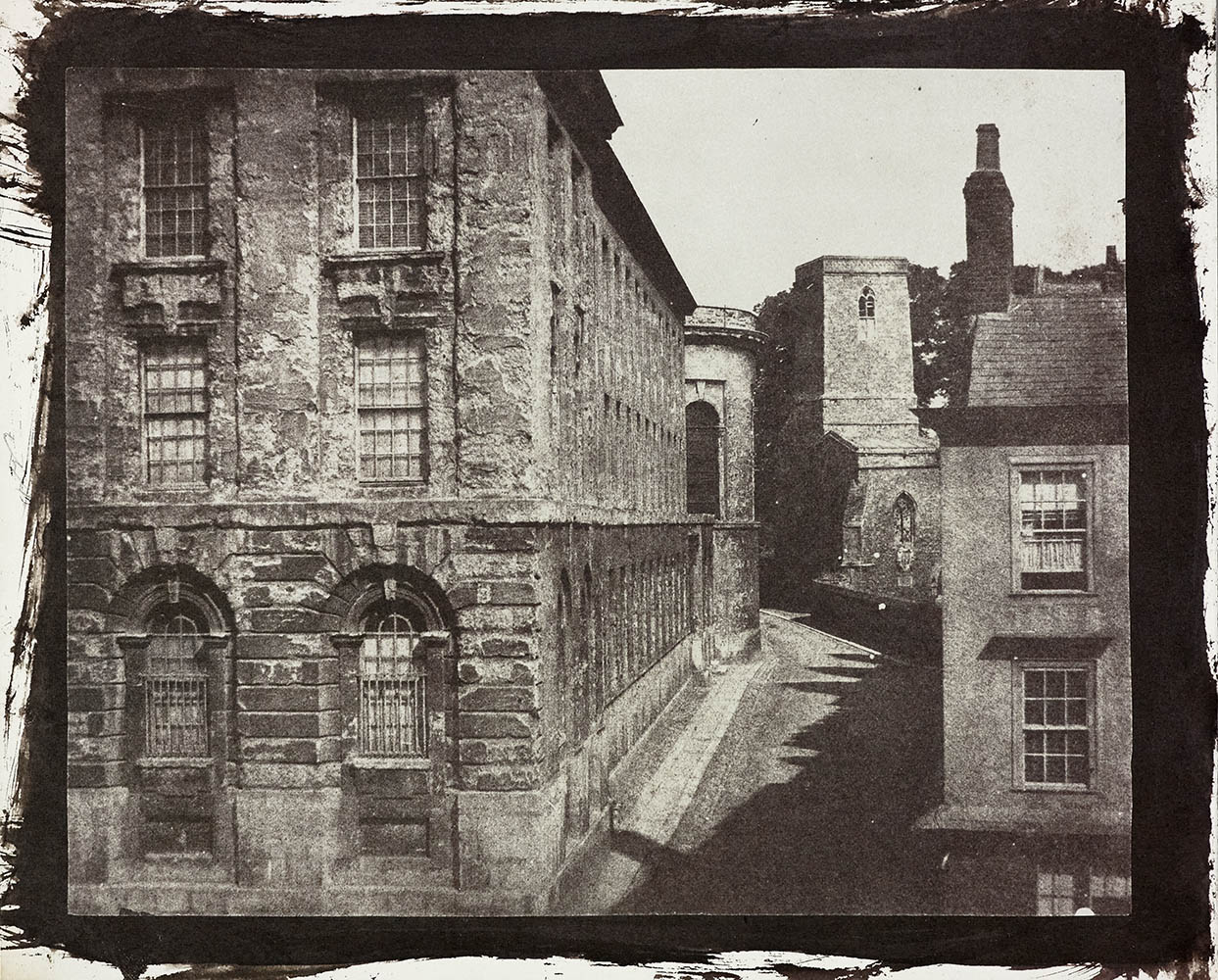

Published in 1844, “Part of Queen’s College, Oxford” was the very first plate in the first number of The Pencil of Nature. The Spectator complimented the documentary power of photography, noting that the plate illustrated “the abraded surface of the stone front with a strikingly real effect.” The Literary Gazette echoed this thought: “the time-worn abrasions in the stone are felicitously recorded.” However, I’m much more taken with the insight of the reviewer for the Art-Union. Faced with the productions of an unfamiliar art, he thoughtfully considered that this picture was “the most perfect that can be conceived; the minutest detail is given with a softness that cannot be imitated by any artistic manipulation; there is nothing in it like what we call touch; the whole is melted in and blended into form by the mysterious agency of natural chemistry.”

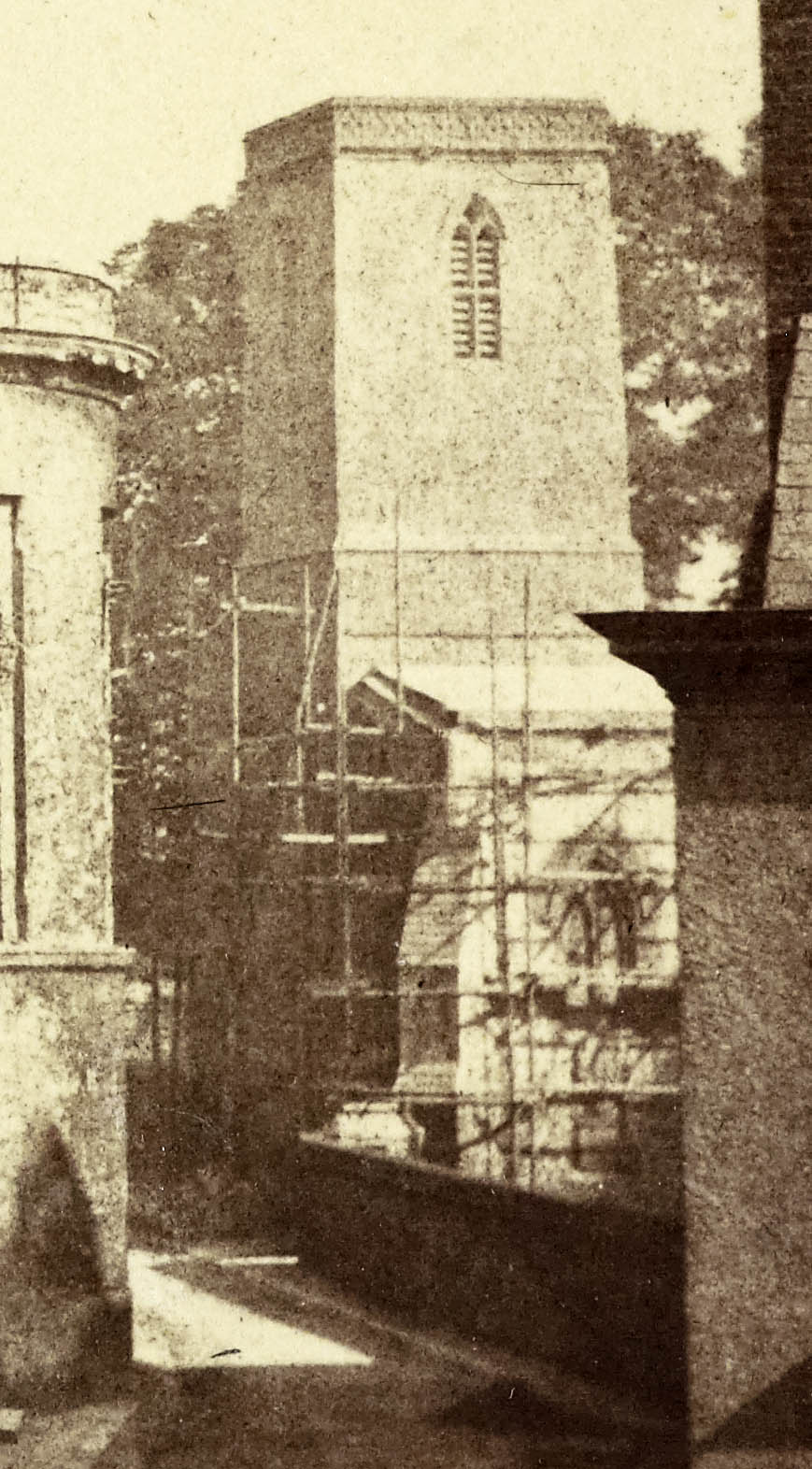

In his accompanying text in The Pencil of Nature, Talbot positioned his photograph in a temporal sphere: “this building presents on its surface the most evident marks of the injuries of time and weather, in the abraded state of the stone, which probably was of a bad quality originally. The view is taken from the other side of the High Street – looking North. The time is morning. In the distance is seen at the end of a narrow street the Church of St. Peter’s in the East, said to be the most ancient church in Oxford.” This particular print was never trimmed and thus never actually published, but I chose it to remind us that every single print and negative in Talbot’s work is unique. Each was coated by hand and each preserves distinctive marks of its maker.

I believe the dating of this wonderful picture to be 4 September 1843, for a couple of days later Henry wrote to Lady Elisabeth. She had dropped him off at Abingdon and he “walked from thence to Oxford … the weather has been exceedingly fine both Monday, Tuesday & today, and I have made about twenty views each day, some of which are very pretty – but the number of picturesque points of view seems almost inexhaustible.”

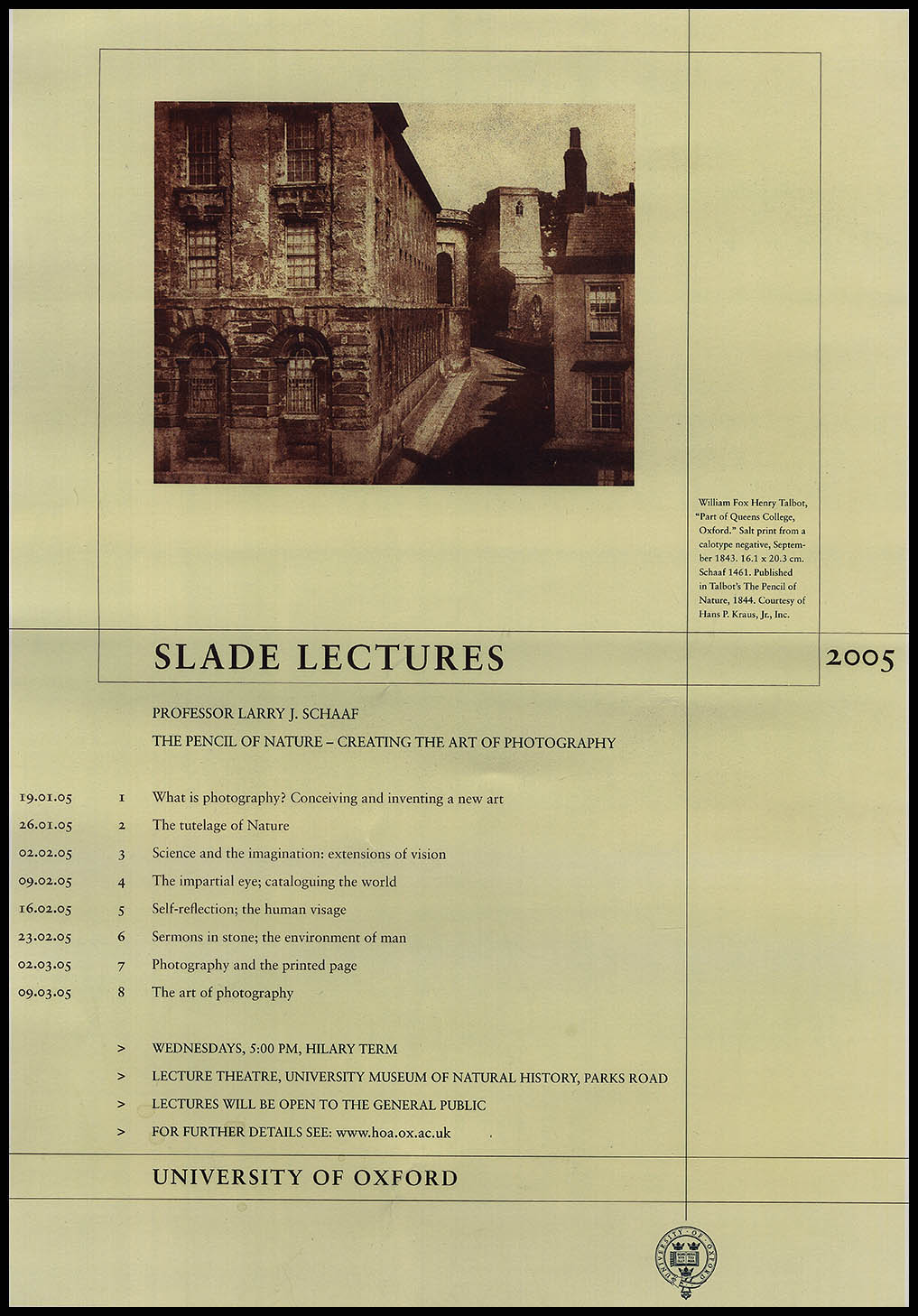

From the first time I saw this particular ‘part’ of Oxford it has ranked among my top favourite Talbot pictures. If I may, it is one of Talbot’s most ‘photographic’ photographs. It also represents on Henry’s part a daring confidence in his new art. It became the theme song for my series of Slade Lectures at Oxford in 2005, defining what a photograph might be. Because I had insisted on using real 35mm slides rather than powerpoint, the Slade Electors very kindly decided to accommodate me in one of the few remaining spaces where the lights could be dimmed to a proper theatre level. That proved to be the auditorium of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, where I stood at the lectern conveniently located just past my companion dinosaurs. In spite of modern pressures, Oxford has managed to keep itself looking pretty much as Talbot would have seen it. Each week the audience would enter to a richly detailed full screen slide of this image and they were invited to think about how they would have approached photographing the familiar site. Since I was based at All Souls College nearby, often I would observe people who had attended the lecture standing at the end of Church Lane, dangerously dodging the now-heavy traffic of the High Street, trying to imagine how Talbot had come to the vision that he had. I daresay that most came away even more impressed with his work.

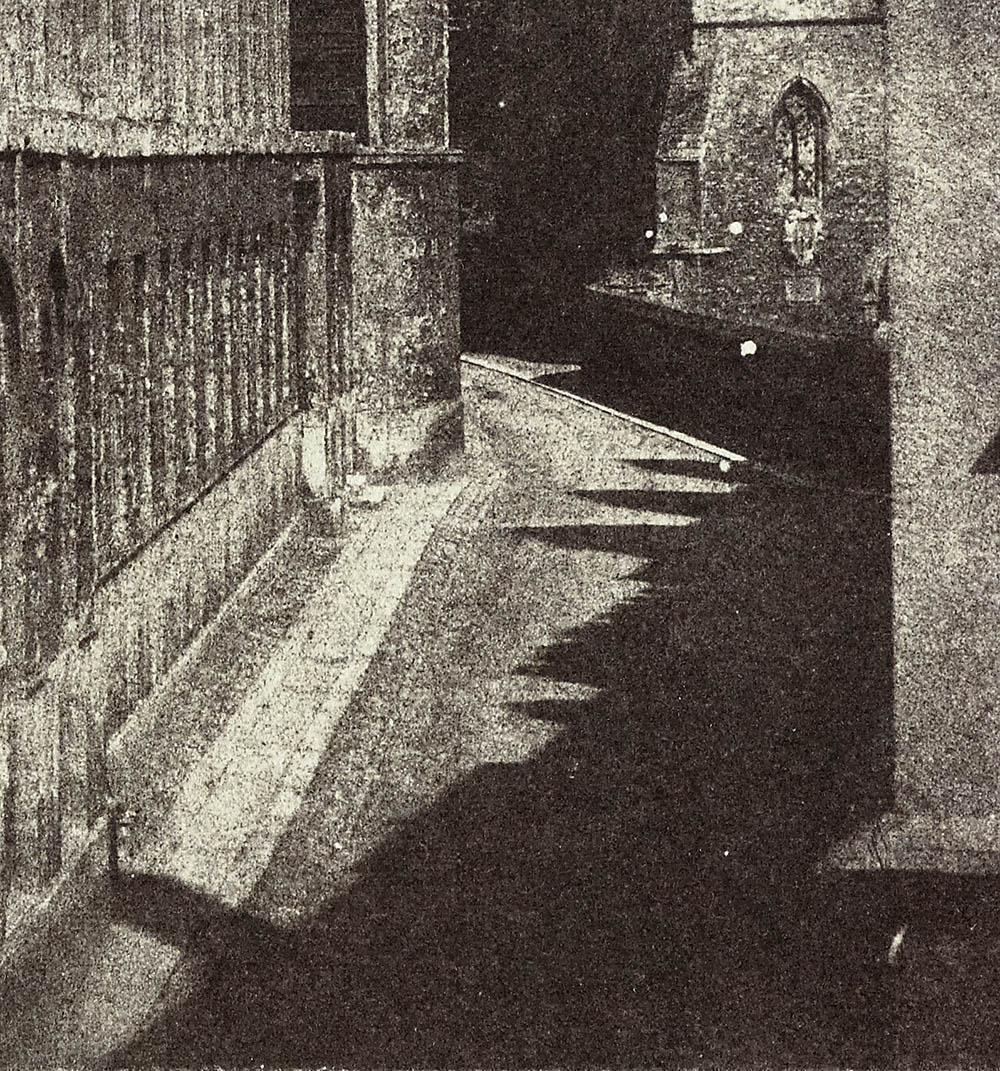

What an extraordinary picture this is! I cannot imagine any sketch artist, painter, or printmaker contemporary with Talbot so severely truncating the surrounding buildings. Indeed it claims to represent only a “Part of Queen’s College,” but what artist would select just this corner and crowd it into the left side of the image? Talbot was brazenly saying that this is photography. Dame Nature, operating through the optics of his camera, accepted Talbot’s framing and took a particular slice out of the physical world, making no concessions for the borders. The image is all the more real for that because it sees things as we see them, selectively, relying on our imagination to build up a composite of the wider context.

But even more insistant than the framing is the dominance of the shadow in the centre of the photograph. It rather than the college building becomes the central subject of the photograph. Those who have visited Oxford know “the gray spires of Oxford, against the pearl-gray sky,” but their effect is even more striking on a sunny day, for their shadows permeate every available space. While light is the true currency of photography, its shadows are an inescapable companion. In his first paper on photography, read before the Royal Society in London on 31 January 1839, Talbot revealed one of his strongest reactions to the new art. In the section On the Art of Fixing a Shadow, Henry confessed that photography “appears to me to partake of the character of the marvelous … the most transitory of things, a shadow, the proverbial emblem of all that is fleeting and momentary, may be fettered by the spells of our ‘natural magic’ and may be fixed for ever in the position which it seemed only destined for a single instant to occupy … such is the fact, that we may receive on paper the fleeting shadow, arrest it there, and in the space of a single minute fix it there so firmly as to be no more capable of change, even if thrown back into the sunbeam from which it derived its origin.”

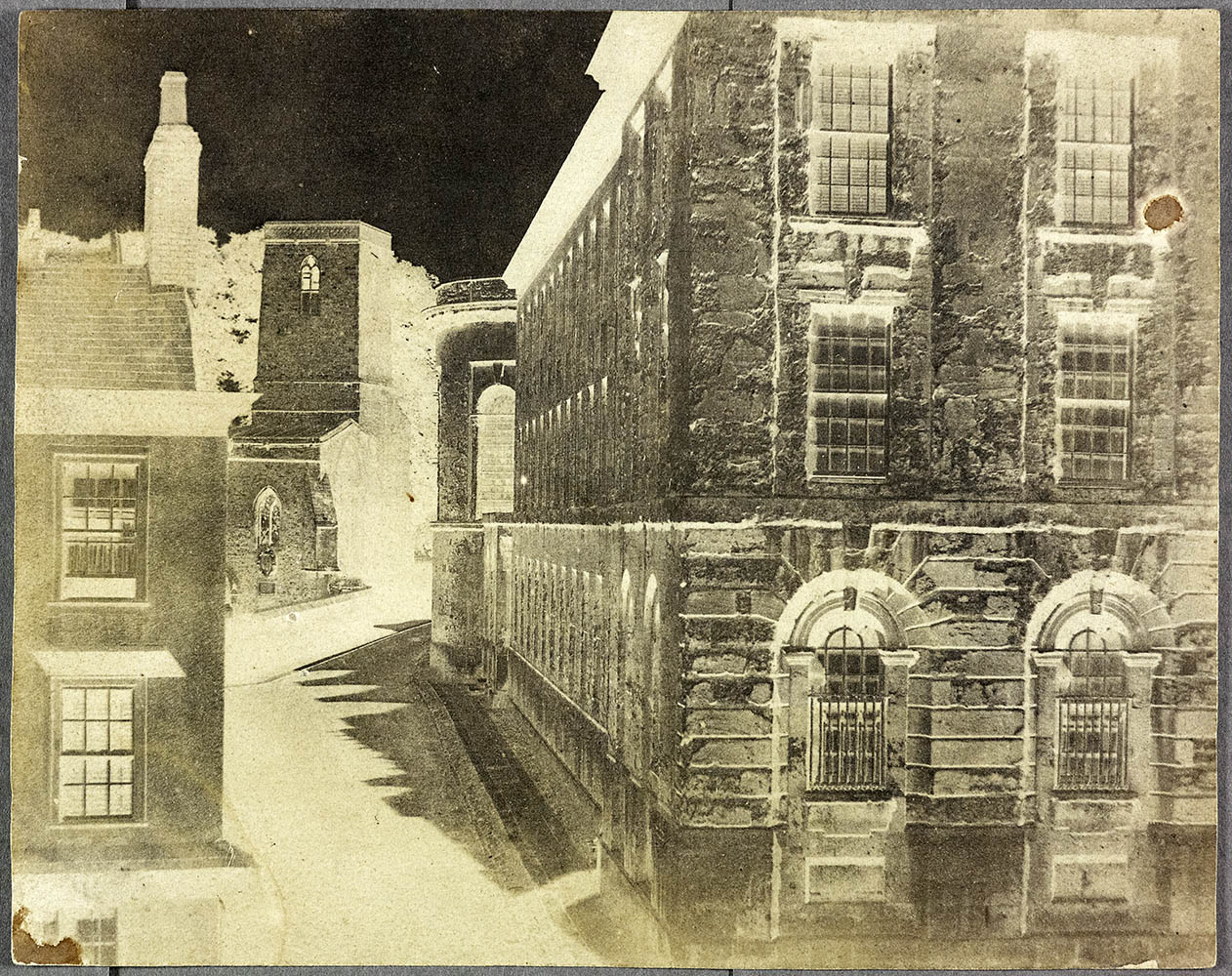

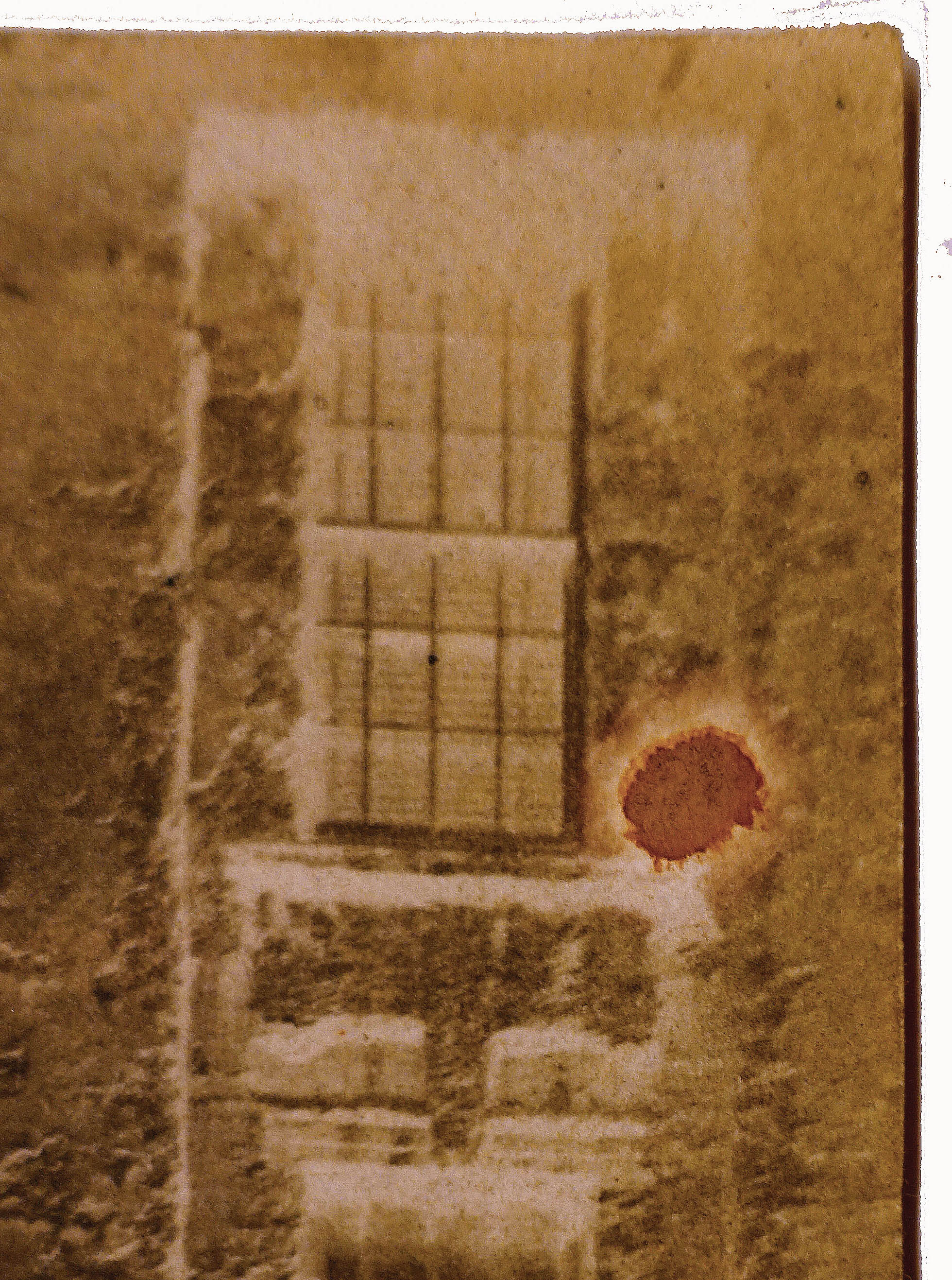

Talbot had positioned his camera in one of the upper rooms of the Angel Inn, a coaching inn on the High Street, like others slowly falling victim to changing traffic patterns with the advent of the railways. The building is still there. It was a marmalade shop when I first visited it in the 1970s and has since gone through several identities, presently as a coffee shop. The negative for this marvelous image still survives. To me, sometimes negatives are more striking than the prints made from them, as was the case of David Kinnebrook’s “Lady in Abbey Ruins” published last week. Here however, while the negative is highly interesting in and of itself, the jagged central shadow is less dominant, less engaging, and one does concentrate on the architecture itself without distraction. But as pretty as this negative was, a problem emerged.

At some point in the printing process, Nicolaas Henneman or one of his assistants had an accident. Chemicals of some sort were splashed on the negative. I think that they bleached areas, not only the lower left corner but most noticeably this spot in the upper right. I expect that the red splotch was an attempt to re-touch the damage, an attempt obviously judged to be unsuccessful. A similar fate was suffered by at least one other negative for The Pencil of Nature, a copy of the bust of Patroclus, but Talbot had photographed this plaster so many times that it was easy to find a substitute. In his text for the last plate published in this part book, Talbot observed that “a very great number of copies can be obtained in succession, so long as great care is taken of the original picture. But being only on paper, it is exposed to various accidents; and should it be casually torn or defaced, of course no more copies can be made. A mischance of this kind having occurred to two plates in our earliest number after many copies had been taken from them, it became necessary to replace them by others; and accordingly the Camera was once more directed to the original objects themselves, and new photographic pictures obtained from them, as a source of supply for future copies. But the circumstances of light and shade and time of day, &c. not altogether corresponding to what they were on a former occasion, a slightly different but not a worse result attended the experiment.”

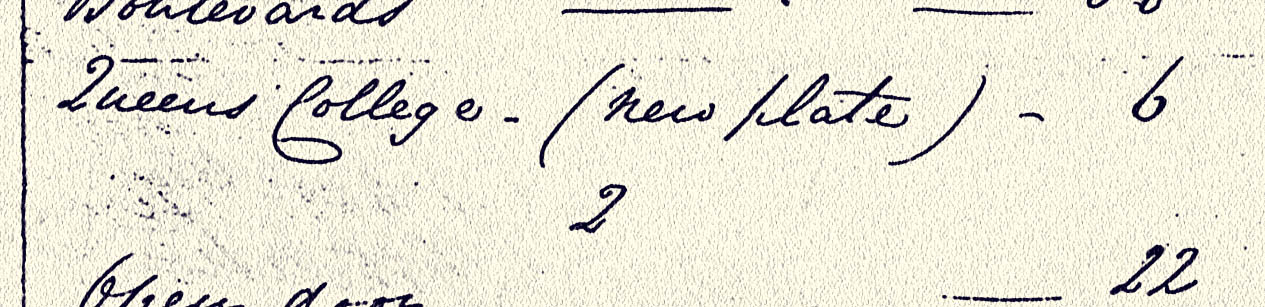

The Pencil of Nature was issued in fascicles, a more affordable format for the buyers, but more importantly the serial publication gave Henneman time to produce a sufficient number of prints. In modern parlance, it was also a ‘print on demand’ book, for as stocks of a certain part ran low Henneman would make more photographic plates to fill up the already printed letterpress. Sometime in early Spring 1846, the damage to the original forced bringing a new negative into play.

I believe that this was taken by Nicolaas Henneman rather than by Talbot and it is an additional demonstration that in spite of the acolyte’s boundless enthusiasm and energy, his photographic vision never evolved as much as it had for the inventor. Queen’s is given a bit more space, but the time of day is poorly chosen and the framing is certainly awkward. Talbot had been chastised about vertical convergence (perhaps a subject for a future post) and was careful to keep his architectural lines straight, as the human mind wrongly expects. Henneman accepted what physics imposed and pointed his camera upwards, inexplicably trying to compensate for it by tilting the camera bed, which straightened the lines of the coffee house at the expense of those of Queen’s. The timing is unfortunate, for instead of the lively jagged shadow drawing our attention to Queen’s Lane, the shadow merely suppresses it. Perhaps Henneman thought that this emphasised the buildings more, perhaps he just accepted the time of day that way convenient. It would not have made nearly as impressive a statement to kick off The Pencil of Nature.

The accounting sheet that reveals the new plate can be pretty reliably dated. The ‘new plate’ of Queens College was printed after part four of the Pencil of Nature was issued in June 1845 and before part five was fully ready in December of that year. What is often not recognized is that Talbot originally planned for The Pencil of Nature to have fifty plates spread over twelve parts. Because of production and other difficulties, the project was cancelled after half that number, giving us an incomplete sense of the grand plan originally envisioned by Talbot. He wanted to include photographs by others, including at least one by Adamson & Hill, and give a wider range of camera views. Of the ‘Odd Plates’ listed but not yet published, only Hagar in the Desert made it into part six.

St. Peter’s in the East, now the library for St Edmunds, intrigued Pevsner as being “without any doubt the most interesting church in Oxford. It has work of all medieval periods, and is fascinatingly jumbled up.” When was Henneman’s replacement plate taken? Henneman was technically accomplished and here we see the paper calotype negative yielding a surprising amount of detail. A vital clue, overlooked by me thirty years ago, was spotted by Professor Graham Smith. He pointed out the scaffolding adorning St. Peter’s recorded in the replacement plate and traced this restoration work to 1844/1845. So unless evidence turns up of earlier work on St. Peter’s, it seems most likely that Henneman imperfectly copied Talbot’s photograph, rather than the master refining an earlier draft of this image.

The worn stone of Queen’s that so bothered Talbot was eventually re-faced, leaving us with the visual dilemma today that the building now looks younger than it did to Talbot nearly 175 years ago. Parts of Lacock Abbey suffer a similar inversion, as the National Trust takes the architecture back to a period before when Talbot photographed his own home. Tricky stuff, that time.

Larry J Schaaf

Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, The Pencil of Nature (London: Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans, No. 1, June 1844. • WHFT, Part of Queen’s College, Oxford, salt print from a calotype negative, probably 4 September 1843, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1296/3; Schaaf 1461. • The Spectator, v. 17, no. 838, 20 July 1844, p. 685. • Literary Gazette, no. 1432, 29 June 1844, p. 410. • The Art-Union, v. 6, 1 August 1844, p. 223. • WHFT to Elisabeth Feilding, 6 September 1843, Talbot Correspondence Document no. 04875. • Winifred M. Letts, “The Spires of Oxford (Seen from a Train),” in Hallow-e’en, and Poems of the War, (New York: E. P. Dutton and Co., 1916). pp. 7-8. • Read before the Royal Society on 31 January 1839; WHFT published the full text as Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing, or the Process by Which Natural Objects May be Made to Delineate Themselves, Without the Aid of the Artist’s Pencil (London: R. and J.E. Taylor, 1839). His reference to throwing it back into the sunbeam derives from the French naturalist, Adelbert von Chamisso’s 1814 Peter Schlemihls wundersame Geschichte. Of the numerous translations, an illustrated one is A.S. Rapoport, The Marvellous History of The Shadowless Man (London: Holden & Hardingham, 1913). • WHFT, Part of Queen’s College, Oxford, calotype negative, probably 4 September 1843, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1284; Schaaf 1461. • Nicholaas Henneman’s establishment, Accounting of plates for The Pencil of Nature, Fox Talbot Collection, The British Library, London; LAM-57. • Attributed to Nicolaas Henneman, Part of Queen’s College, Oxford, salt print from a calotype negative, 1844/1845, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1288/15; Schaaf 1462. • I laid out some of the unpublished text and plates in my Introductory Volume to H. Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, Anniversary Facsimile (New York: Hans P. Kraus, Jr., Inc., 1989). I continue to hope to publish some day, perhaps in conjunction with an exhibition, a reconstruction of the original fifty plate series, for it would give a much more balanced view of how Talbot perceived his art. • Graham Smith’s observation was in his review of the Facsimile in the Print Collector’s Newsletter, v. 20 no. 4, September/October 1989, p. 148. The 1844/1845 restoration is documented in the Royal Commission’s Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Oxford (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1939), p. 143. • Jennifer Sherwood and Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Oxfordshire (Hammondsworth: Penguin Books, 1974 ), p. 295.