Guest post by Hilary Macartney

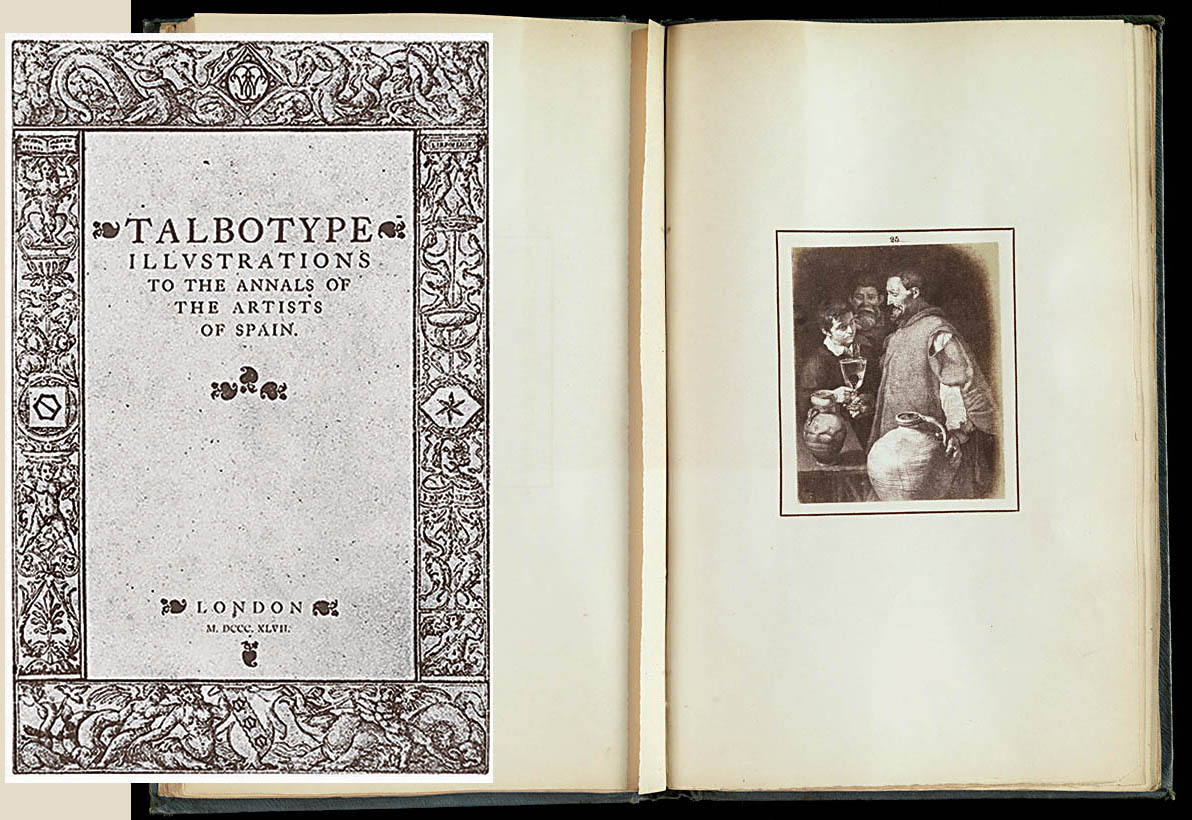

Today’s guest editor was the mover and shaker not only behind an extended research program on early photographic illustration but also for a lovingly re-created facsimile of the first book on art history ever to be illustrated with photographs. Sir William Stirling Maxwell’s 1847 volume of Talbotype Illustrations to the Annals of the Artists of Spain, building on the promise of Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, sought to supplement the art historical text with precise and inexpensive illustrations. The training of art historians would never be the same.

LJS

1848 saw the publication of Sir William Stirling Maxwell’s seminal book on Spanish art, Annals of the Artists of Spain. His addition of a volume of illustrations ‘copied by the sun’ created the world’s first photographically illustrated book on art. At a time when Art History was only beginning to emerge as a scholarly discipline, the invention of photography promised open access to the great works of art throughout the world. Its 68 photographs were produced in 1847 by Nicolaas Henneman. One of the reasons that Spanish art was still much less well known than Italian art was that it had been less often reproduced through traditional engravings. The supplementary photographic volume was produced in an edition of just 50 presentation copies so its circulation was limited. Nevertheless, it was of enormous significance in pointing the way towards the use of photography as an essential tool not only of academic art history but in the study of art generally, and especially in widening access to art through illustrated books.

Henneman and Stirling Maxwell’s enterprise was fraught with difficulties. Museums had no experience in welcoming photographers to copy their works of art and Stirling himself was not yet a major collector. Instead, he gathered together some small, portable artworks owned by himself and fellow Hispanophiles Richard Ford and Ralph William Grey for photography. Original oil paintings had to be reproduced via painted copies or prints – much like in traditional engraved illustrations. In fact, Spanish printmaking was another of Stirling’s major interests and he included photographs of four Goya etchings after paintings by Velázquez as illustrations of both artists. The case of a little painted relief sculpture of the Infant Christ and St John presented other challenges, like the then near-impossible task of translating colour and tone into a coherent monochromatic photographic image, whilst also ensuring that the lighting was sufficiently even and the shadows cast by the frame were minimised. This last problem was referred to by Henneman in an 1847 letter to Stirling.

Infant Christ and St John (Ford Collection, London) and Henneman’s photographic copy

Infant Christ and St John (Ford Collection, London) and Henneman’s photographic copy

Ultimately, a fatal problem proved to be the inherent vulnerability of silver prints and the illustrations suffered severe fading soon after they were mounted in the books. When the second, posthumous edition of the Annals appeared in 1891, no mention was made of the Talbotype Illustrations, no doubt due to their outdated technique and deteriorated state. Their existence was not entirely forgotten by specialist collectors and photographic historians, however, and interest was gradually revived in the course of the 20th century as the methodology of early photography and Art History both became increasing areas of study. The rarity and fragility of the volume meant that few people, even specialist scholars had seen a copy.

The idea for a collaborative research project about the Annals’s Talbotypes began emerging about fifteen years ago, spearheaded by José Manuel Matilla, Head of Drawings and Prints at the Prado Museum in Madrid and myself. José Manuel had discovered a copy of the Annals Talbotypes volume in the Museum’s library, and after seeing some rare proofs from Henneman’s stock in the Huellas de Luz exhibition on Talbot at the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid in 2001 became convinced of the need for a facsimile edition. My own fascination with the volume began during preparation of my doctoral thesis on Stirling Maxwell as scholar of Spanish art for the Courtauld Institute (2003). José Luis Colomer, Director of the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica in Madrid also became committed to promoting the importance of Stirling Maxwell, and the National Media Museum in Bradford became another of the project partners. Together, we set up the Stirling Maxwell Research Project, based at the University of Glasgow, in 2010. Core funding was secured from Santander, with additional support from the Kress Foundation, the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin.

From the start, we agreed that a facsimile and critical edition would be the main output of our project. But deciding what kind of facsimile would be possible or appropriate and how to achieve it required careful consideration and a lot of discussion. We located and studied 23 of the 50 copies produced, held in public and private collections worldwide, and commissioned high-quality digital images of the best examples of each of the illustrations. In the Talbot Collection at the National Media Museum, we examined the nearly 500 proofs relating to the Annals Talbotypes that remained in Henneman’s stock after the edition copies were bound up. These provided precious insight into the many challenges of photographing art in 1847. Printed slips inserted in the bound edition, offering replacements for ‘faulty impressions’ if required, seem to indicate that many of the loose proofs were intended for that purpose.

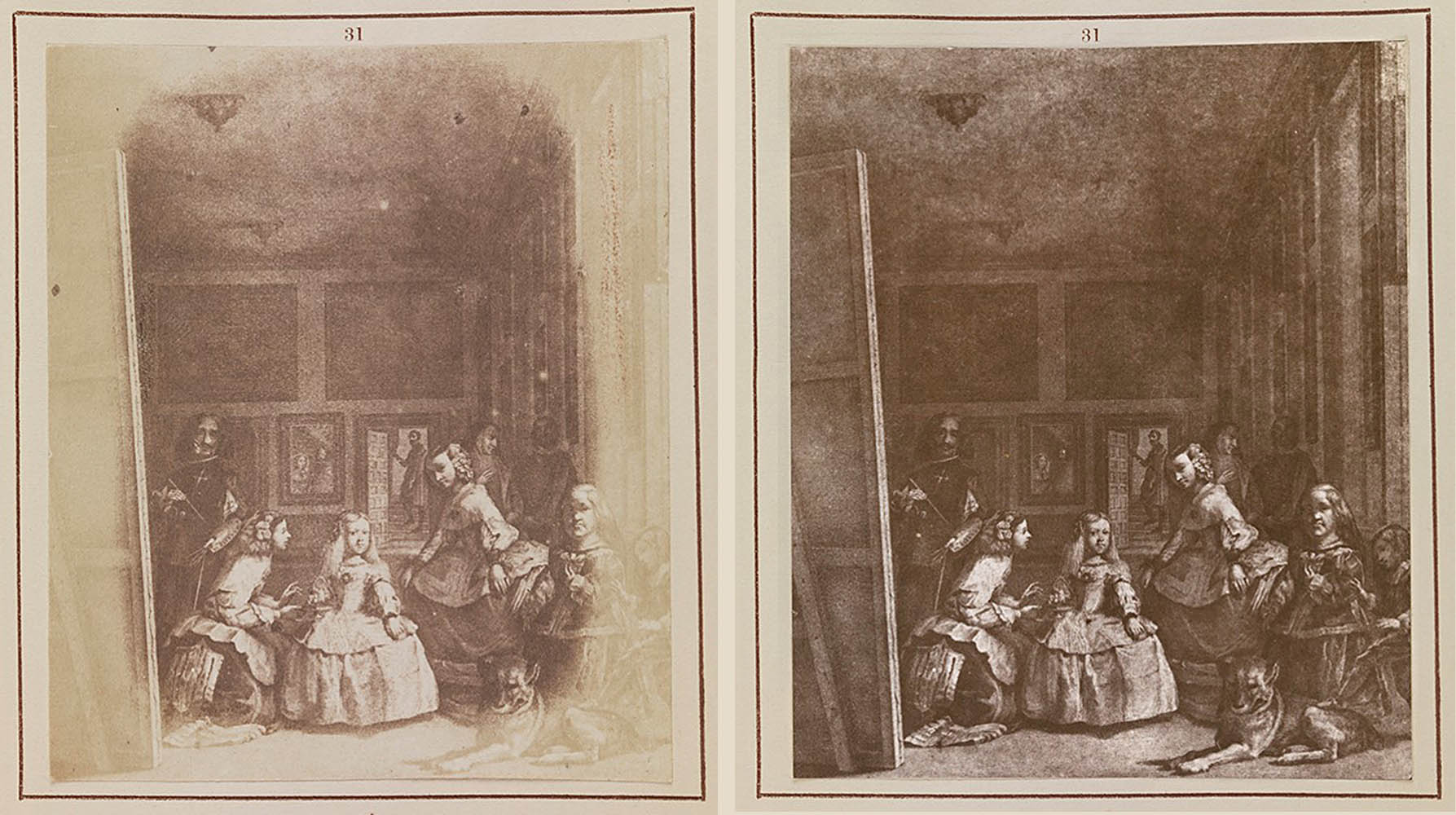

All the known copies of the volume were found to show substantial deterioration, though the Prado’s copy turned out to be one of the best preserved – as indeed is the British Library’s. In a few cases, there were no good examples amongst Henneman’s stock either.

What would be the point of producing a new book that reproduced faded images? Professor Schaaf was the Academic Consultant on our project and we decided to follow the lead that he had established in his 1989 facsimile of The Pencil of Nature. We agreed upon the goal of an idealised facsimile which would reconstruct for modern readers the look and feel of the original as they must have seen it when first published. We decided to embrace the idea of digital reconstruction but particularly avoiding inventing anything not present in any of the originals. We defined the ideal copy as the most perfect state of a work as originally intended, an understanding of which could only emerge following examination of as many actual copies as possible. These basic principles were agreed at a colloquium in Bradford attended by the project team and invited specialists. The painstaking process of reconstruction was carried out by Victor Raposeiras and Ángel Manuel Rodríguez at the Prado’s Photographic Archive, under our supervision and with advice from Professor Schaaf.

Copy of an engraving of Velázquez’s Las Meninas – salt print original and digital reconstruction

Copy of an engraving of Velázquez’s Las Meninas – salt print original and digital reconstruction

Other constraints of practicality and affordability led to further major decisions – and compromises – about materials and techniques. We didn’t want to produce something that was so authentic-looking that it was prohibitively expensive. For example, we didn’t get the original book-cloth specially recreated, but went for something off-the-peg – as Stirling had done – that looked similar to the original in colour and texture. And our images were not made using the Talbotype process and then tipped into each volume by hand, but directly printed in ink, using current technology, onto the pages of modern paper. We tried to imagine what Stirling would have done in our position, and we were in no doubt that he would have embraced today’s digital technology, just as he adopted the latest reproduction methods in 1847-48. Certainly Talbot, with his quest for photogravure, would have enthusiastically supported this decision.

Our new edition was launched at the Prado Museum in May this year, accompanied by the exhibition Copied by the Sun/Copiado por el sol, curated by José Manuel Matilla and myself, in association with the National Media Museum as the main lender. The exhibition was a unique opportunity to see some of the original artworks alongside painted copies and engraved or lithographed intermediaries that were photographed for the volume, as well as a number of examples of the volume itself, and many of the proofs from Henneman’s stock. It was seen by more than 67,000 visitors over the summer.

Copied by the Sun/Copiado por el sol exhibition at the Prado, 2016

Copied by the Sun/Copiado por el sol exhibition at the Prado, 2016

Last month, we celebrated the launch of the book, hosted by the Stirling Maxwell Centre in the University of Glasgow’s Department of Special Collections as part of as part of the Institute for Photography in Scotland’s Season of Photography 2016. Also on display was a selection of early photographic and Stirling Maxwell material from the University Library’s collections. D. O. Hill & Robert Adamson were commissioned by Stirling to produce some photographs that were not used in the final volume of illustrations for the Annals. Their large 34×42 cm. calotype negative of the Surrender of Breda, which was one of the highlights of the Prado show, appears to be of the lithograph of the painting supplied by Stirling and may have been intended for a special volume by Hill & Adamson showcasing their photography.

D. O. Hill & Robert Adamson, Velázquez’s Surrender of Breda, calotype negative, University of Glasgow Library

D. O. Hill & Robert Adamson, Velázquez’s Surrender of Breda, calotype negative, University of Glasgow Library

The event reunited several of the team who contributed to the research project and the publication, including Brian Liddy, one of our key contacts at the National Media Museum in Bradford and now part of this Talbot Catalogue Raisonné project at the Bodleian.

Jim Tate, Hilary Macartney and Brian Liddy at the Glasgow opening in October

Jim Tate, Hilary Macartney and Brian Liddy at the Glasgow opening in October

Jim Tate was formerly Head of Conservation and Scientific Analysis at the National Museums of Scotland, where he had already conducted research on calotypes. For our project he carried out the first scientific analysis of the Annals Talbotypes with the help of Maureen Young of Historic Environment Scotland. The results are included in the volume of studies that accompanies the facsimile edition. Thanks to the National Library of Scotland, we were able to carry out non-destructive examination, principally using X-ray fluorescence and microscopy, of their copy of the volume, and to compare results with related material in the National Media Museum and similar examples in the National Galleries and National Museums of Scotland, including an album of Hill and Adamson photographs.

Maureen Young conducting XRF examination in 2013

Maureen Young conducting XRF examination in 2013

We were especially interested in using modern technology to re-examine the various theories about the causes of the edge-fading typical of the salted paper prints that were mounted in books. Though our analysis sample was limited, the results obtained were consistent with the action of damp and sulphur-polluted air being diffused to the centre of the volumes. We found no evidence of similar action in the loose prints sampled from Henneman’s stock – and likewise no evidence that the adhesive used to mount the plates in the bound volumes had contributed to the fade patterns. This research is likely to have implications for other early photographically illustrated works such as Talbot’s Sun Pictures in Scotland.

Stirling was modest in his expectations about the impact of his volume of photographs. He concluded the Preface by hoping that if his friends who had received presentation copies “and others, who do me the favour to accept this little collection, shall feel any interest in its contents, … my end will be achieved, and my labour amply rewarded.” We hope he would also feel gratified by the recently rekindled interest in his volume.

Hilary Macartney

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Dr. Hilary Macartney is a Lecturer in Spanish/Hispanic Art at the University of Glasgow. Since 2010, she has directed the Stirling Maxwell Research Project there. • Title page for the Talbotype Illustrations to the Annals of the Artists of Spain; digital reproduction by Victor Raposeiras and Ángel Manuel Rodríguez, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. • Henneman’s photographic copy of the Waterseller of Seville by Velázquez, from the engraving by Blas Ametller, Talbotype Illustrations, no. 25, Prado. • Henneman’s 17 March 1847 letter is in the Maxwell of Pollok Papers, on deposit at Glasgow Archives, T-PM 130. • Infant Christ and St John, Ford Collection, London; Henneman’s photographic copy, Talbotype Illustrations, no. 13, Prado. • Printed slip in Talbotype Illustrations, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven. • Henneman’s photographic copy of Las Meninas by Velázquez, from the engraving by Pierre Audouin, Talbotype Illustrations, no. 31, Prado; digital reconstruction by Victor Raposeiras and Ángel Manuel Rodríguez, Prado. • H. Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, Anniversary Facsimile (New York: Hans P. Kraus, Jr., Inc., 1989), six fascicles with an Introductory Volume by Larry J. Schaaf. • In 2103, Maureen Young of Historic Environment Scotland conducted XRF examinations of original Hill & Adamson photographs in an album given to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, National Museums of Scotland. • Copied by the Sun: Talbotype Illustrations to the Annals of the Artists of Spain by Sir William Stirling Maxwell, facsimile and critical edition edited by Hilary Macartney and José Manuel Matilla, 2 vols. (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado/ Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, 2016). Available through booksellers or directly from the Prado or CEEH.