Guest post by Geoffrey Batchen

Guest post by Geoffrey Batchen

This is the second blog posting from my old friend and ex-pat Professor Geoffrey Batchen – his first was about a recent acquisition for his private collection. He teaches art history at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, specializing in the history of photography. His many and influential books include Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (1997); Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History (2001); and Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph (2016).

LJS

There are many fine qualities for which William Henry Fox Talbot deserves due honour, but it is fair to say that business acumen is not one of them. Photography was invented in an age of entrepreneurial capitalism, but Talbot struggled to find ways to turn his discovery of the calotype process to his commercial advantage. His personality and education were well suited to scientific experiment and exposition (in that spirit he had simply given away the details of his photogenic drawing process in February 1839) but not, it seems, to sales, the balancing of books and the seeking of profits.This was a problem exacerbated by Talbot’s class position, as is made clear in a reminiscence published in 1895 by Benjamin Cowderoy about his time as manager of the Reading Establishment. According to Cowderoy, he worked part-time for Talbot during 1846 to conduct “all correspondence, issue licenses under the patents, and attend generally to the business of supervising the distribution and sale of the pictures.” He remarks that the “stock of pictures grew to inconvenient proportions in the hands of such a gentleman as Mr Talbot, occupying a high position in aristocratic society,” reminding his readers that “in those days” the “younger sons of dukes” did not, at risk of social approbation, “enter into mercantile offices.” Talbot was no duke’s son, but his extended family certainly enjoyed that sort of social status. As a consequence, Cowderoy opined that Talbot experienced “perplexity and embarrassment through the accumulation of merchantable products which the usages of society would not allow him personally to ‘liquidate’.”

Despite this potential embarrassment, Talbot had taken out a patent on the calotype process on 8 February 1841, which meant that anyone who wanted to use it for professional purposes had to apply to him for a license to do so. A number of would-be commercial photographers entered into negotiations with Talbot to achieve that end.

One of those was the coal merchant Richard Beard, the first person in England to actively pursue the commercial possibilities of photography. He invested in various aspects of the daguerreotype process in the hope that it could eventually be made to produce acceptable portraits. In early 1840, for example, Beard bought one half of the English rights to Wolcott’s Reflecting Apparatus, a camera invented in New York that relied on a concave mirror rather than a lens to reflect light onto a prepared daguerreotype plate. Sometime later he acquired these rights in their entirety, taking out a patent on the camera and related innovations on 13 June 1840. Beard also hired the services of John Frederick Goddard, until then a lecturer in optics and natural philosophy, to improve the chemistry of the daguerreotype. By September 1840 Goddard claimed to be able to bring exposure times down to one to four minutes by using bromide of iodine in his formula. This made portraiture possible, even if still difficult. Nevertheless, according to The Morning Chronicle of 12 September 1840, in Goddard’s first portraits “the eyes appear beautifully marked and expressive and the iris is delineated with a peculiar sharpness as well as the white dot of light on it, and this is done with such strength and clearness as to give the portrait a really astonishing appearance of life and reality.” Claiming his rights to the discovery as Goddard’s employer, Beard included the breakthrough in his patent document of 9 December 1840.

One of those was the coal merchant Richard Beard, the first person in England to actively pursue the commercial possibilities of photography. He invested in various aspects of the daguerreotype process in the hope that it could eventually be made to produce acceptable portraits. In early 1840, for example, Beard bought one half of the English rights to Wolcott’s Reflecting Apparatus, a camera invented in New York that relied on a concave mirror rather than a lens to reflect light onto a prepared daguerreotype plate. Sometime later he acquired these rights in their entirety, taking out a patent on the camera and related innovations on 13 June 1840. Beard also hired the services of John Frederick Goddard, until then a lecturer in optics and natural philosophy, to improve the chemistry of the daguerreotype. By September 1840 Goddard claimed to be able to bring exposure times down to one to four minutes by using bromide of iodine in his formula. This made portraiture possible, even if still difficult. Nevertheless, according to The Morning Chronicle of 12 September 1840, in Goddard’s first portraits “the eyes appear beautifully marked and expressive and the iris is delineated with a peculiar sharpness as well as the white dot of light on it, and this is done with such strength and clearness as to give the portrait a really astonishing appearance of life and reality.” Claiming his rights to the discovery as Goddard’s employer, Beard included the breakthrough in his patent document of 9 December 1840.

With these improvements in hand, Beard opened a commercial daguerreotype studio in the Royal Polytechnic Institution in London on 23 March 1841. He mistakenly presumed that his patent rights over the Wolcott camera and Goddard’s technical refinements of the daguerreotype process placed him outside the jurisdiction of Louis Daguerre’s own patent. Daguerre had been granted this patent on 14 August 1839 to cover the use of his invention within “England, Wales and the Town of Berwick-on-Tweed, and in all Her Majesty’s Colonies and Plantations abroad,” meaning that anyone in these designated areas wishing to practice the daguerreotype was legally obliged to pay Daguerre or his agent a license fee. Threatened with the closure of his studio, on 23 June 1841 Beard concluded negotiations with Miles Berry, Daguerre’s patent agent in England, and purchased the English patent rights to the daguerreotype process. On 16 July 1841 Beard also signed a license agreement with Daguerre and the son of Nicéphore Niépce, Isidore.

As a consequence of all this, Beard was very familiar with the legal and financial complexities associated with running a photographic business. However it should be noted that, despite being the patent holder, Beard very probably made no photographs himself. He instead hired operators like Goddard to take the photographs in his own studio and busily set about selling licenses to others to open studios throughout England. As part of the licensing agreement, these studios were obliged to stamp their products with the words ‘Beard Patentee,’ wherever they were made. By the end of 1841, Beard had licensed twelve other studios in towns like Plymouth, Bristol, Cheltenham, Liverpool, Nottingham, Southampton, Brighton, Bath, Manchester, Norwich and Guilford. By May 1842, he had also opened two further studios under his own name in London. This led to hundreds of ‘Beard’ daguerreotypes being made during this period by photographers other than Beard: in these early years, Richard Beard was to photography as Colonel Sanders is to fried chicken.

Following Talbot’s announcement of the calotype process, Beard approached him with a view to establishing a franchise system for paper photography similar to the one that already covered the taking of daguerreotype portraits. By this time Talbot was quite familiar with Beard’s operation. He had received a letter from Charles Wheatstone on 24 February 1841 telling him that Wheatstone had “recently seen some miniature portraits taken by the American process which are absolutely perfect; I could not have thought the expression of the features could be so excellently preserved.” Perhaps prompted by this assessment, it seems likely that Talbot visited the Beard studio shortly thereafter, before it had officially opened to the public, and had some portraits of himself taken. If they were indeed made around the first week of March, they would be the earliest extant daguerreotypes produced by this studio and thus the earliest extant commercial photographic portraits made in England.

Two of these portraits of Talbot have survived, both small ninth-plates. However neither could be described as ‘absolutely perfect’.

In one of them Talbot stares grimly at the camera, his eyes cast in shadow and his hair disheveled. In the other, he stares off to his right, hair now inelegantly combed across his bald forehead. Both are murky and indistinct. Talbot’s features are captured with chemical certitude but any hint of personality has been subsumed to the long exposure time and strain of posing. He looks, in other words, much like all of the Beard studio’s other subjects, like someone still learning how to look like himself in a photograph. These portraits have been mounted in black wooden hanging frames, one surrounded by an elaborate dolphin and pheasant mount and the other by a chased metal rectangle.

Both have a green label bearing the words “Wolcott’s Reflecting Aparatus” [sic] on the back and one of them has the trademark term “Beard Patentee” inscribed in relief on the front. Beard’s name therefore appears under this picture like a signature. But this is a signature, not of an artist/author, but of a business owner and patent holder. As a consequence, Talbot’s stolid countenance finds itself disconcertingly sandwiched between two “legal” declarations of Beard’s proprietorial rights to photography.

Both have a green label bearing the words “Wolcott’s Reflecting Aparatus” [sic] on the back and one of them has the trademark term “Beard Patentee” inscribed in relief on the front. Beard’s name therefore appears under this picture like a signature. But this is a signature, not of an artist/author, but of a business owner and patent holder. As a consequence, Talbot’s stolid countenance finds itself disconcertingly sandwiched between two “legal” declarations of Beard’s proprietorial rights to photography.

On March 10, John Johnson, an American employee of Beard’s and the co-inventor of the Wolcott camera, sent one of the metal mirrors used in the camera (he calls it a “metallic speculum”) to Talbot’s London address, along with extensive written instructions on how it should be situated and manipulated within the apparatus. Johnson speaks of the “prepared material” that Talbot would use in the camera to make a photograph, presumably a reference to his calotype paper. It seems likely, then, that Johnson was among those on the team who took Talbot’s portrait and that they discussed the making of portrait photographs at length, including paper photographs. A few months later Beard and Talbot began negotiations about the possible commercial application of the calotype process.

A number of relatively formal letters between Beard and Talbot or their representatives survive on the topic, the earliest of them exchanged in July 1841, with Beard trying to persuade Talbot to allow him to issue calotype licenses to cover particular towns, much as he had done for the daguerreotype. Talbot considered making Beard his sole agent, but despite the exchange of several drafts of an agreement vetted by their respective lawyers, no deal was ever signed. Beard expressed an interest in taking out a license for his own establishment that would cover the photographing of both people and buildings, but they disagreed over what percentage of any income from the use of the calotype would go to Talbot. Nevertheless, on 7 April 1842, Goddard, described by Beard as “one of my most Competent assistants” and accompanied by a letter of introduction from Beard, visited Talbot’s home in Lacock Abbey to learn the calotype process.

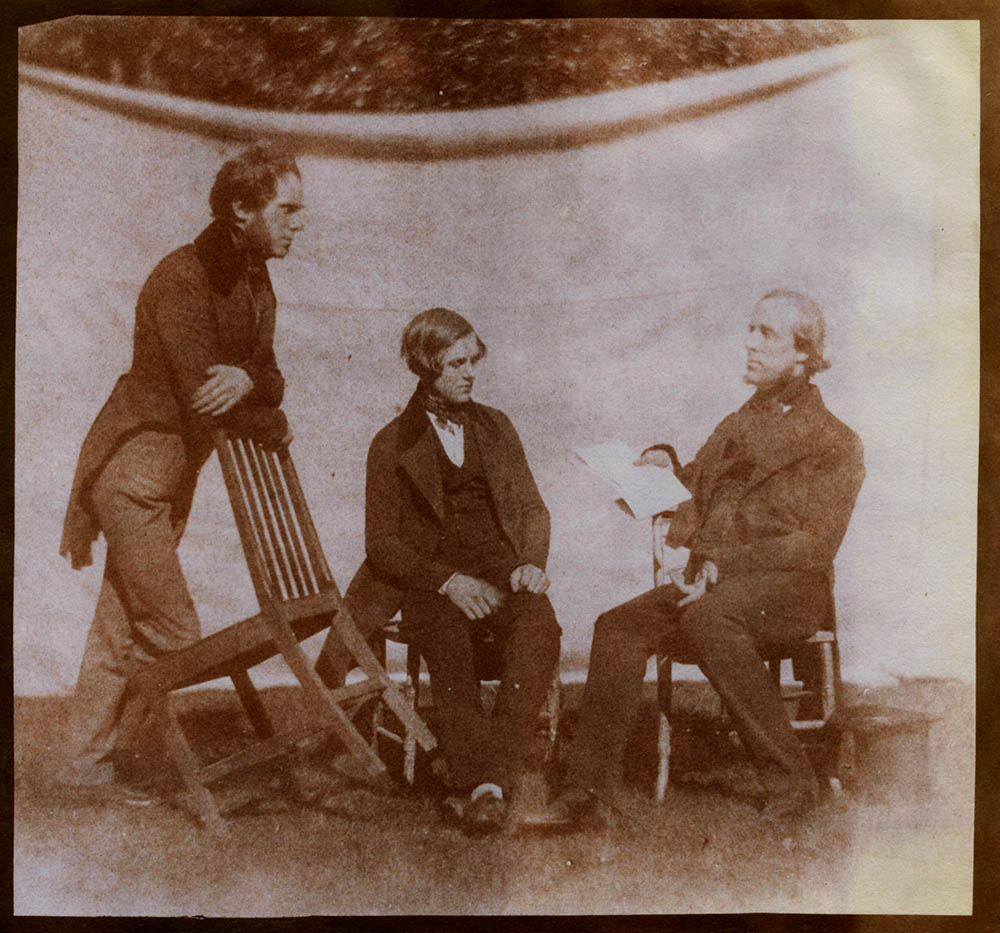

At least fifteen individual photographs were made during this visit, including a number that featured Goddard. Among them was one close-up portrait, focusing just on Goddard’s head; according to Larry, “its dark background, tight framing and octagon clipped corners are reminiscent of some daguerreotype portraits,” implying that Goddard may have brought his own experience in Beard’s studio to the taking of this example. Other pictures were more ambitious in pose and ambition. One, taken on 8 April, shows Goddard and Nicolaas Henneman, Talbot’s servant and assistant, shaking hands, as if they had just met (their top hats are held in their spare hands). In other words, they recreate a moment from the day before, all the while pretending that the camera is not present. This “acting between living persons,” as John Herschel called it, borrowed its conventions from both a popular parlor game and from history painting, and before that from carved sculptural friezes. The images that result often retain this sense of staged two-dimensionality, with figures carefully displayed in shallow space for a camera they are nevertheless strenuously ignoring.

In a picture of Goddard speaking to Henneman and Charles Porter, another servant, taken by Talbot on 8 April 1842, Henneman leans forward over the back of a chair precariously balanced on only two legs, while Goddard’s left hand has its fingers curled upward as if caught in mid-speech. These complex poses had to be held for over a minute if the impression was to be left that this photograph was indeed taken, as Talbot put it, “from the life.” He sent a print of this photograph, along with others, to Robert Hunt, who wrote back on 22 April to thank him, commenting in similar terms that “Mr Goddard appears to the life in the group.” Goddard himself wrote to Talbot on 14 April to tell him that he had not yet had an opportunity to experiment with the calotype process but that “I am having a room at the Western Establishment fitted up for the purpose and the necessary apparatus etc made and in a few days hope to be doing something with it.” Beard himself wrote again on April 21 to assure Talbot of his “intention to employ my utmost energy in making it [calotypy] useful to various purposes.” And there the correspondence seems to have ceased. Although Beard never did come to a satisfactory arrangement with Talbot, Goddard continued to take an interest in calotypy. After he opened his own daguerreotype studio in 1845 in Ryde, on the Isle of Wight, he contacted the Reading Establishment with a view to visiting it, but nothing seems to have come of this effort either.

In January 1842, Richard Beard’s greatest rival, the French-born photographer Antoine Claudet, also approached Talbot about the possibility of purchasing a license to take calotype portraits. The story of their relationship, and a discussion of the photographs that resulted. will be told in a forthcoming blog entry.

Geoffrey Batchen

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • The tintype portrait of Geoff was taken by Kari Wehrs in 2015. • Beard Studio, Portrait of Richard Beard, CDV, ca. 1860, Geoff Batchen Collection. • Richard Beard Studio, Daguerreotypes of William Henry Fox Talbot, probably Spring 1841, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, LA5516 and LA5517. • Richard Beard Studio, Verso of mounted daguerreotype of William Henry Fox Talbot, probably Spring 1841, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, LA5516. • WHFT, Portrait of John Frederick Goddard, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 7 April 1842, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-369/17, Schaaf 4182. • Larry J Schaaf, Sun Pictures: Catalogue Nine, New York: Hans Kraus Jr., 1999, p. 22. • WHFT, “From the life” – Goddard Instructs Henneman and Porter, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 8 April 1842, Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich, Prot. bd. 58-134; Schaaf 2641. • John Herschel used the phrase “acting between living persons” in a letter to Talbot dated 21 April 1842, responding to the gift of one of these prints. There are at least six known prints from this negative. See Schaaf, The Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), pl. 53. • When Talbot sent a copy of this image to his friend John Herschel, he inscribed it “from the life, in one minute �, H.F. Talbot 1842.” See a discussion of three of the known prints in Schaaf, Sun Pictures: Catalogue Nine, pp. 26-29.