Today’s guest is Rose Teanby, a photohistorian so eager that she single-handedly located the long-neglected grave of the important photographer Robert Howlett and then raised funds for its restoration and rededication. Rose has a particular interest in photographic documentation of the great Victorian engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

In an earlier blog, Talbot’s 16th c Photograph, I examined Henry’s extraordinary panoramic view of the River Thames. Most significant to me was that he preserved the very narrow slice of time when Westminster Abbey once again dominated the landscape, just as it had been designed to do in the 16th century, and could have been photographed then. The Houses of Parliament had been destroyed by fire in 1834 and their replacement (eventually including Big Ben) was just emerging. It was a scene unfamiliar for many generations and one soon to disappear forever. In today’s blog, Rose Teanby examines this rich photograph from the other end of time, seeing it as a recording of emerging modernity.

guest post by Rose Teanby

The panorama of the River Thames has captivated artistic talent throughout the ages. It is no surprise that Talbot chose a view of Westminster as a subject worthy of his calotype in the summer of 1841. Whatever he intended, his image shows London in a state of raw rebirth including the earliest photographic record of any structure designed by the charismatic civil engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859).

Brunel and Talbot had a prickly but symbiotic relationship. As an inventor, Talbot, had devised several methods of locomotion and by 1834 the two men were in correspondence both about technical matters and, in Talbot’s role as a Member of Parliament, securing his support for the Great Western Railway Bill Brunel had been appointed Chief Engineer of the Great Western Railway, making him responsible for determining the most suitable route from London to Bristol. This brought him into contact with Talbot as both enthusiastic advocate of the railways and a protective landowner. Their relationship deteriorated by 1845 when Talbot objected to plans for a branch line cutting through the grounds of Lacock Abbey and Brunel replied in frustration that Talbot’s “reference to ‘the Solicitor’ is generally understood to mean that there is no desire to settle anything peaceably.”.

Before this rupture, Brunel commenced work on the Hungerford Bridge in April 1841, just two months before Talbot’s photograph. Brunel was inextricably linked to the iconic River Thames, building over, underneath and on it. It was on its muddy banks that he created the largest ship the world had ever seen, the SS Great Eastern, and he almost lost his life in a flood during the building of the Thames Tunnel in 1828. From his office at Duke Street in Westminster, he planned the engineering projects subsequently photographed by Talbot.

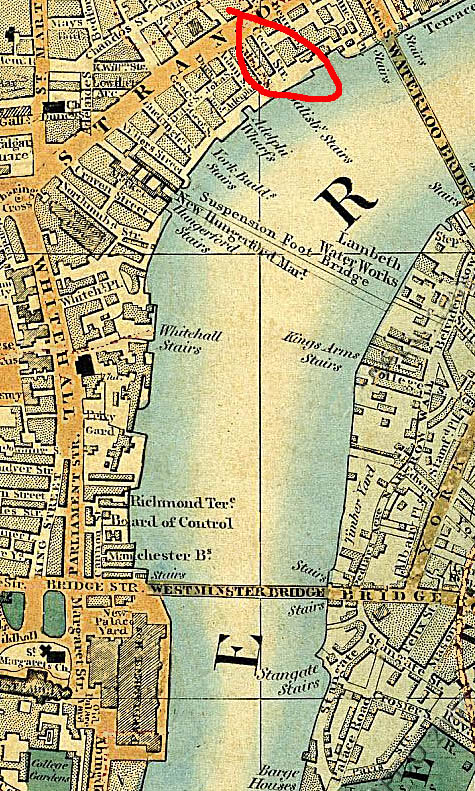

The high vantage point of Talbot’s Cecil Street flat allowed him to capture a central section of London heaving with the tumultuous transition from medieval to modern. Barely visible in front of Westminster Abbey are the embryonic new Houses of Parliament and the original Westminster Bridge, which would be demolished and replaced between 1854 and 1862.

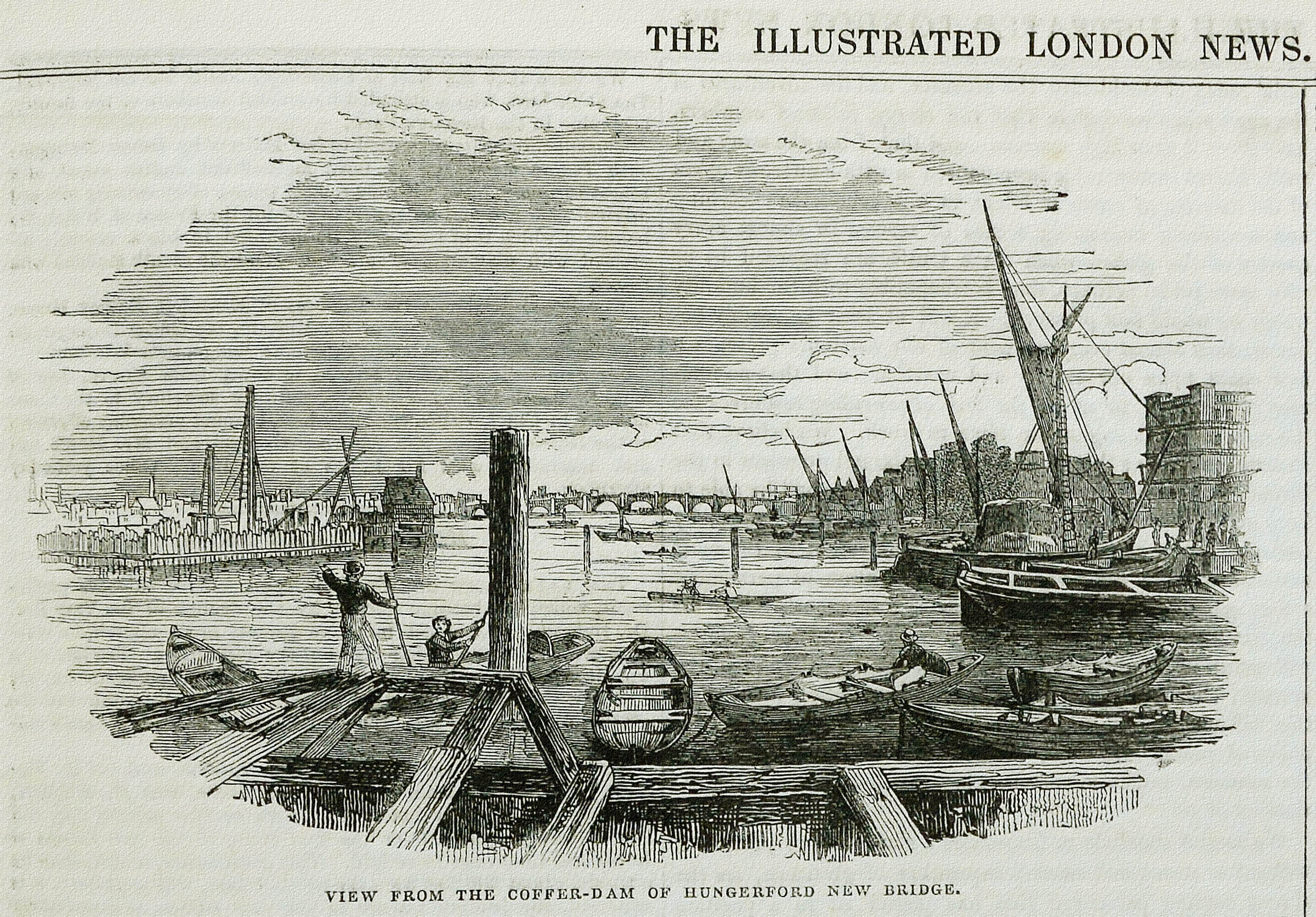

At the end of March 1841, The Examiner reported that workmen were “busily engaged in landing immense numbers of planks and wooden piles at Hungerford market” in preparation for construction of the bridge. But Talbot’s view includes a mysterious cylindrical shape rising from the Thames. It is the cofferdam or footings of one of the two piers of Brunel’s first suspension bridge, the Hungerford Bridge. Sheet pilings had to be driven into the bed of the river to construct the perimeter of the cofferdam and here we see it as the North pier is being constructed. The 35 foot tall towers of ‘Brother Jonathan’, a steam pile driver imported from Utica, New York (James Nasmyth’s famous steam hammer was still being designed) were put to work building the abutments at the edge of the river.

The Hungerford was a footbridge, intended to bring more custom to the newly rebuilt Hungerford Market at Charing Cross. At the time of its construction, the Morning Post reported that steam boat traffic from Hungerford Pier had risen tenfold, to more than a million landings by 1839. The report predicted great success for the “Italian Style” chain suspension footbridge, providing access to the market via “a safe and agreeable promenade”. Fully 1360 feet long when completed, for a toll of a half-penny it brought new customers from the South Bank across the Thames to the market.

There are several possible reasons why Talbot structured his photograph as he did. When in London he normally stayed at his parents’ house in Sackville Street but this very central address offered no photographic views. He took up temporary residence in Cecil Street presumably because of the panoramic view of the Thames, positioned at a sharp bend in the river providing an excellent vista of Westminster (the view in the other direction, including the desirable subject of St Pauls, was presumably obscured by other buildings).

Well aware of the fine arts, Henry may have been inspired by a very similar view of the Thames towards Westminster by Canaletto, sketched and painted a century earlier from a comparable location near Somerset House. With this photograph taken from his window, Talbot heralded a new breed of artist celebrating the Thames at Westminster. He introduced a different way of seeing the world, artists’ brushes and paint replaced with silver chloride coated paper and the actinic rays of the sun.

As an MP from 1832 to 1835, was Talbot lamenting the catastrophic destruction of the Houses of Parliament in 1834? There was an all-pervading air of uncertainty with a general election held during the months of June and July 1841. So by focusing his camera on Westminster, Talbot captured the mighty British seat of power at its most vulnerable, invisible to the world in both structure and leadership.

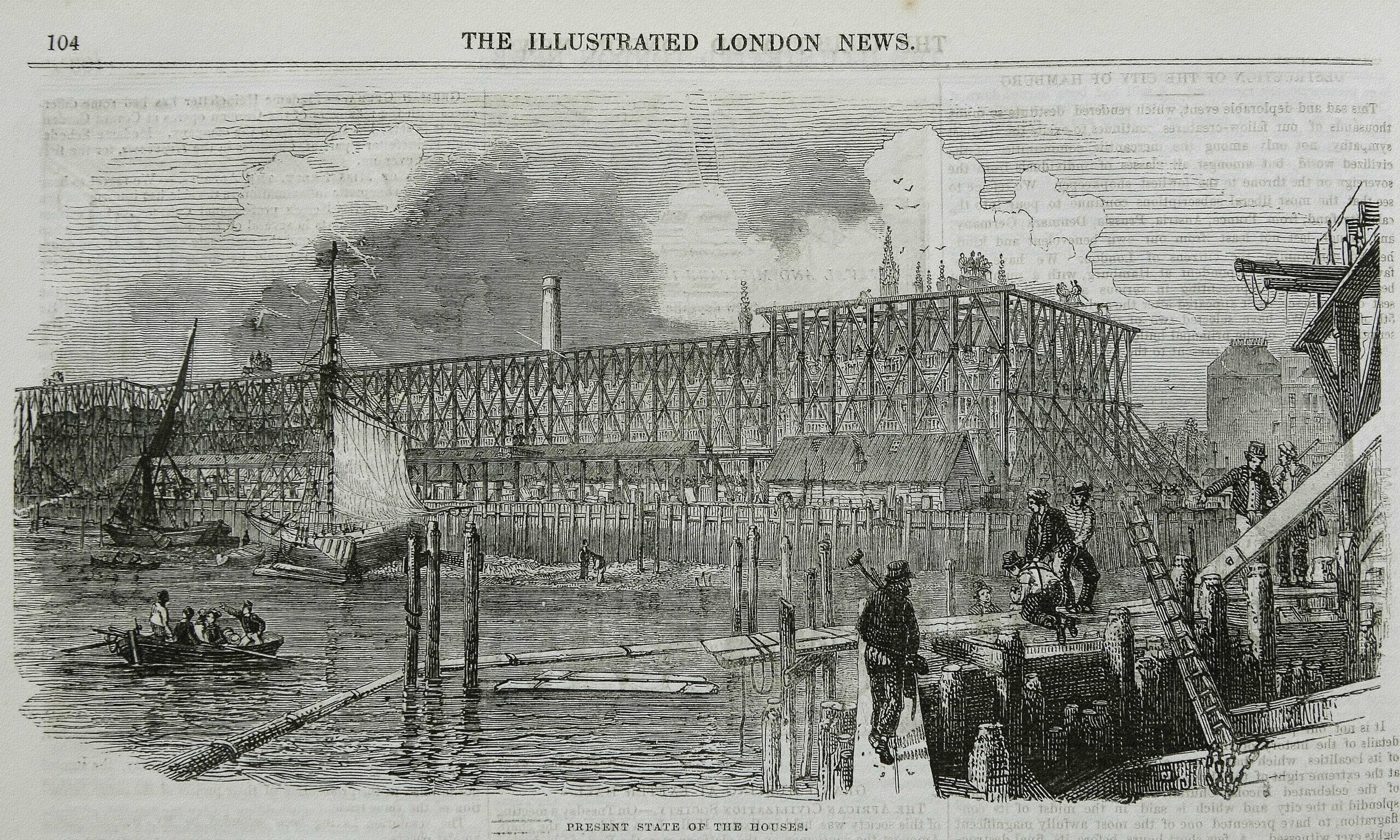

The Illustrated London News optimistically charted the progress of the new Houses of Parliament a year later, remarking “The building is progressing with remarkable rapidity.” This engraving showing significant progress in the construction, hidden beneath a shroud of wooden lattice scaffolding.

Had Talbot returned to Cecil Street then, his photograph would have carried entirely different connotations.

Although there were some construction delays, Brunel’s Hungerford suspension bridge was opened for foot traffic by 1845. Henry had recorded its very beginnings and he would return four years later to photograph its completed state.

By 1858, Roger Fenton’s view of the same area could show the Houses of Parliament almost completed and the Hungerford Bridge sweeping gracefully across the Thames. However, Brunel’s majestic Hungerford Bridge had a relatively short working life of fifteen years, ironically becoming a victim to the pressures of expanding the railway connections at Charing Cross. The site of the crossing had become too precious for a mere footbridge.

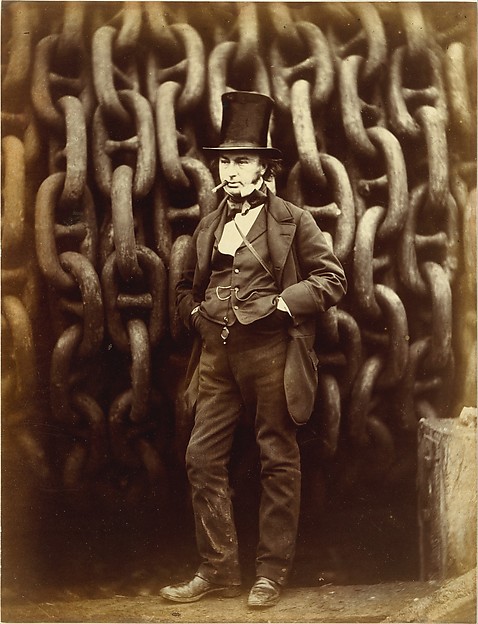

Chains were Brunel’s professional companion throughout his career and a fitting backdrop for his iconic portrait by Robert Howlett in 1857. Although the bridge was demolished, Brunel’s chains were recycled to enable the construction of the breath taking Clifton Suspension Bridge.

The same view of Westminster today contains only the piers from Brunel’s footbridge, incorporated into the structure of Charing Cross railway bridge. Thomas Page’s crossing at Westminster copes admirably with 21st century traffic but Big Ben is now silent, the Elizabeth Tower once again clothed in an exoskeleton of scaffolding for urgent repairs.

Both Talbot and Brunel contributed in different ways to an era of irreversible transition from one way of life to another, building and photographing the herculean efforts made by those at the forefront of engineering. The skyline of London is in constant evolution but Talbot’s glimpse of Westminster remains frozen in time, as he stood at his window looking upriver, towards the sun, on that June day in 1841.

Henry Talbot’s photograph caught this turbulent section of the Thames with an honesty peculiar to photography, devoid of the usual artistic licence employed to sanitise the clutter and chaos. Within the disorder he has caught a unique moment as the past, present and future merge in a single image. This is a vision of London as a victim of its circumstances, a neo Gothic feat of engineering rising from the ashes of disaster and the taming of a famous river with Brunel’s first suspension bridge; London being reinvented as the magnificent capital city of today.

Rose Teanby

• Questions or Comments? Rose Teanby can be contacted at roseteanbyphotography.co.uk. The author would like to thank Dr David Greenfield, BSc PhD CEng MICE, and Clive Cockerton, BSc CEng MICE, of the Institution of Civil Engineers Panel for Historic Engineering Works, for their unparalleled engineering expertise. • WHFT, River Thames in London, from Talbot’s Cecil Street flat, salt print from a calotype negative, June 1841, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-366/50; Schaaf 3705. • The Thames south from Cecil Street, adapted from Cross’s New Plan of London, 1850. • “View from the Coffer-dam of Hungerford New Bridge,” Illustrated London News, 10 September 1842. • Canaletto, London: A view of Westminster from the terrace of Somerset House, ca. 1750, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017. • “Present state of the Houses,” Illustrated London News, 25 June 1842. • WHFT, The Hungerford Suspension Bridge, London, salt print from a calotype negative, summer 1845? Gilman Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.100.608; Schaaf 1219. • Roger Fenton, Westminster from Waterloo Bridge – Houses of Parliament under construction, ca. 1858, salted paper print from a wet collodion negative, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, PH1978:0108. • Robert Howlett, Isambard Kingdom Brunel in front of the chains of The Great Eastern (detail), albumen print from a wet collodion negative, 1857, Metropolitan Museum of New York, 2005.100.11.