In spite of the seemingly perverse efforts of the self-proclaimed ‘World’s favourite airline’, I’ve finally made it to Paris. The occasion is an international conference the subject of which would have been unthinkable a decade ago: Henry Talbot’s first friend in photography, the negative.

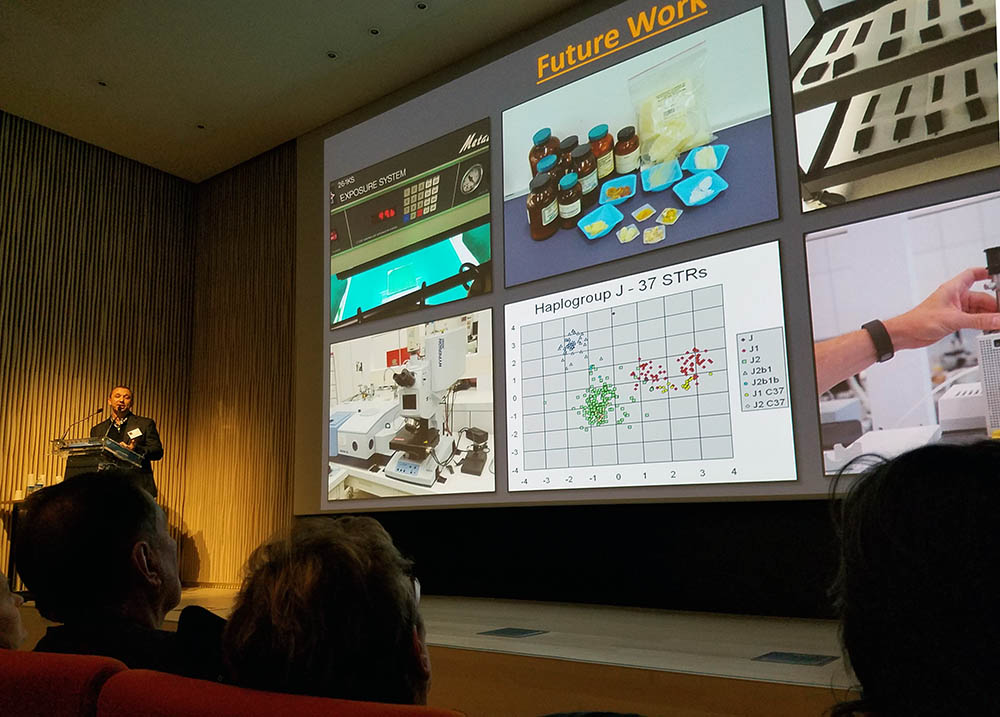

Les négatifs papier français: production, caractérisation, conservation – French paper negatives: production, characterization, preservation – is taking place on the 7th & 8th of December. The French excelled in the late 1840s into the 1850s with paper-negative based photographs of exquisite beauty and technical accomplishment. This conference, held at the Musée de l’Homme , features an international cast of 27 speakers, mostly curators and conservators, with more than 150 attendees from 15 countries. Some of the presentations so far have been about specific collections, but most have dealt with the exciting new scientific research that is evolving that promises to give us a much fuller understanding of these complex early photographs.

Of course I’ll be the contrarian talking about the Englishman Talbot, emphasising the critical role of his pre-calotype photogenic drawings in his aesthetic development and maturation. Since I am writing this before the conference has been completed, here is the provisional programme and I’ll do another blog posting after the end of the conference with a more complete summary of the research findings.

Negatives have often been considered the inconvenient stepping stones to the ‘real’ goal of the print. Ansel Adams famously said that the negative was the score and the print was the performance. Perform well he did, both on the piano and in the darkroom, but without his negatives he would have had nothing. After all, these were the very sheets of film (or in Talbot’s case, of sensitised paper) that faced the sunlight on that particular day in that particular place at that particular moment.

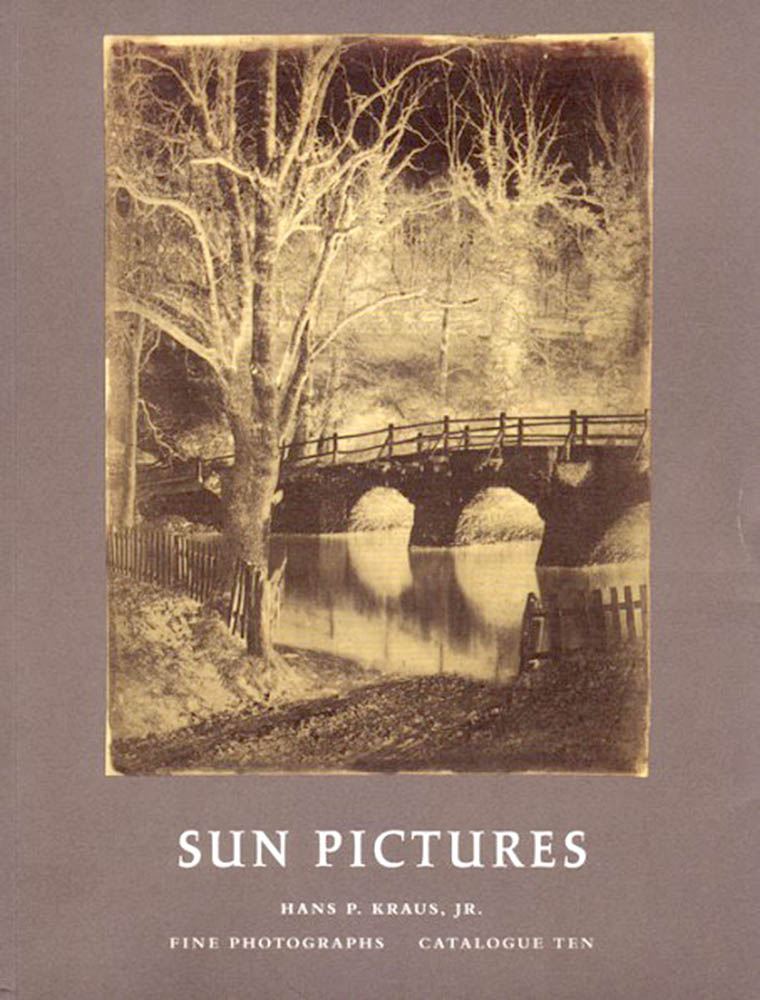

I recall in 2001 when Hans P Kraus, Jr, issued his Sun Pictures. Catalogue Ten. British Paper Negatives 1839-1864, unapologetically featuring nothing but negatives. Hans had seeded previous catalogues with a sprinkling of negatives but never before had they been dominant. His colleagues were initially somewhere between sceptical and derisive, but the public loved it.

In February 2013, Dr Cornelia Kemp took the pioneering step of organising the first conference that I am aware of whose central subject was the negative. Unikat, Index, Quelle. Erkundungen zum Negativ in Fotografie und Film – Unique, index, source: Investigations of the negative in photography and film was an interdisciplinary conference held at the Deutsches Museum in cooperation with the German Society for Photography (DGPh). It was memorialized by a catalogue.

This excellent conference was personally memorable, for it was the last time that I succeeded in using real slides. Dr Kemp was most sympathetic to my arguments that there was nothing like the theatrical aspects and sheer visual joy of excellent 35mm slides, well projected in a properly darkened room. When I arrived (well in advance) the technicians balked a bit in meeting a dinosaur but were most cooperative. But I broke out laughing when the superb quality projector and the various cords all had “removed from museum display” tags. They worked perfectly and were promptly returned to their historical exhibits immediately after the performance. Perhaps I should have been as well.

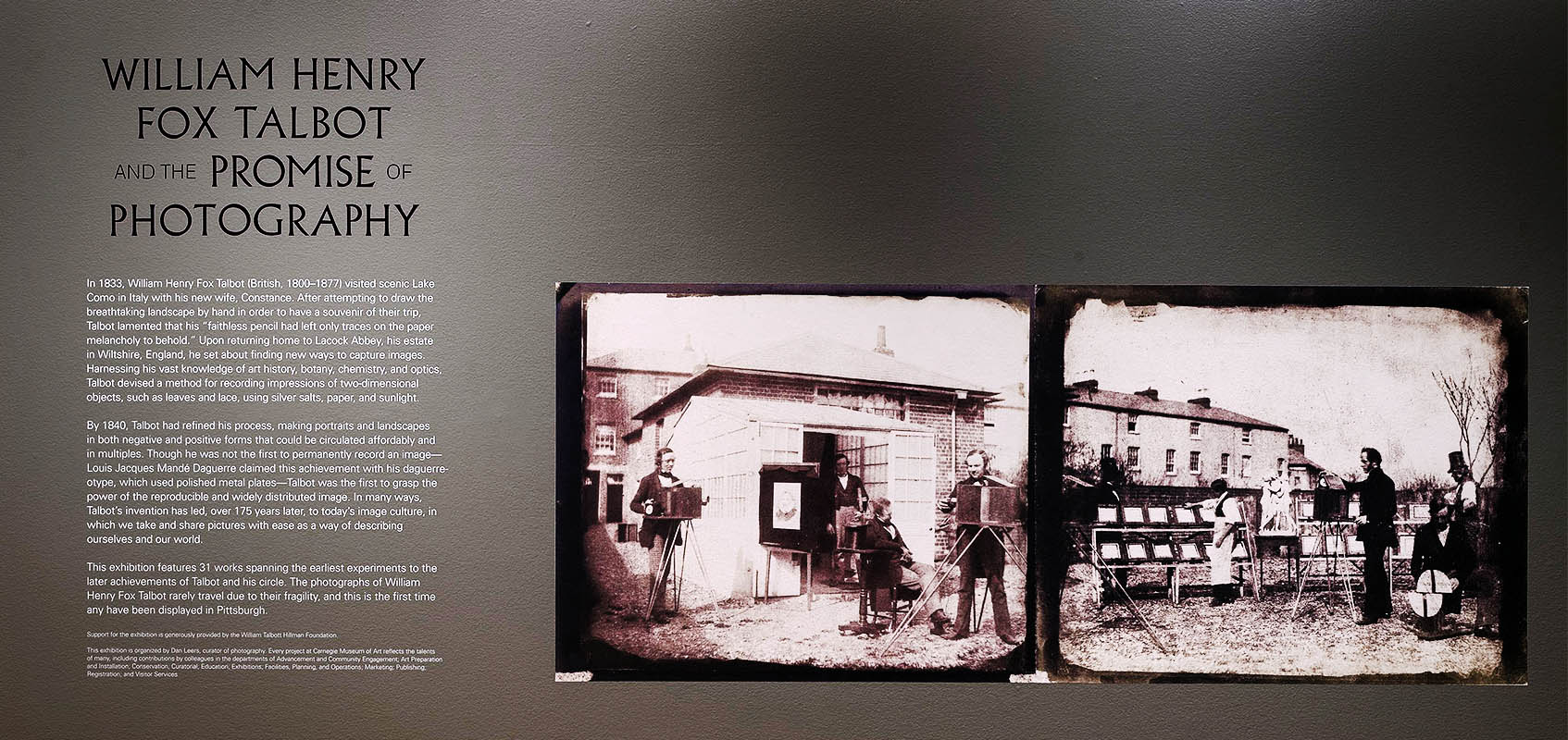

Elizabeth and I had the honor of attending the opening of an exciting new exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. Curated by Dan Leers, William Henry Fox Talbot and the Promise of Photography is accompanied by a small but exquisite catalogue under the same title.

This is the first dedicated Talbot exhibition in the United States in many years. Its impetus was the generous donation by William Talbott Hillman of a significant part of his personal collection of original Talbots (more on Mr Hillman in a moment, and yes, there are indeed three Ts in his middle name). It is a just-right sized exhibition in a just-right sized gallery. There is enough variety to interest just about anybody and ample opportunity to study these rare originals closely. Judging by when I was there and the reports that I have received since, the Museum was a bit surprised and very pleased that the number of visitors has been substantial. I suspect that most of these have never seen an original Talbot before, much less a grouping of this significance. I wonder how many of the visitors were surprised to find themselves deeply intrigued by funny coloured little sheets of paper with images that date back nearly eighteen decades.

The exhibition opened at the Carnegie Museum of Art on 18 November and is up until 11 February 2018. There is a substantial amount of information in the entry panels and wall labels, not so much as to frighten the horses, but enough to guide both new and experienced viewers in what they are seeing.

Max Campbell titled his piece on the exhibition in The New Yorker , “Looking at William Henry Fox Talbot’s Pioneering Photographs—Without Causing Them to Disappear,” and that gets right to the heart of one of the most substantial aspects of this exhibition.

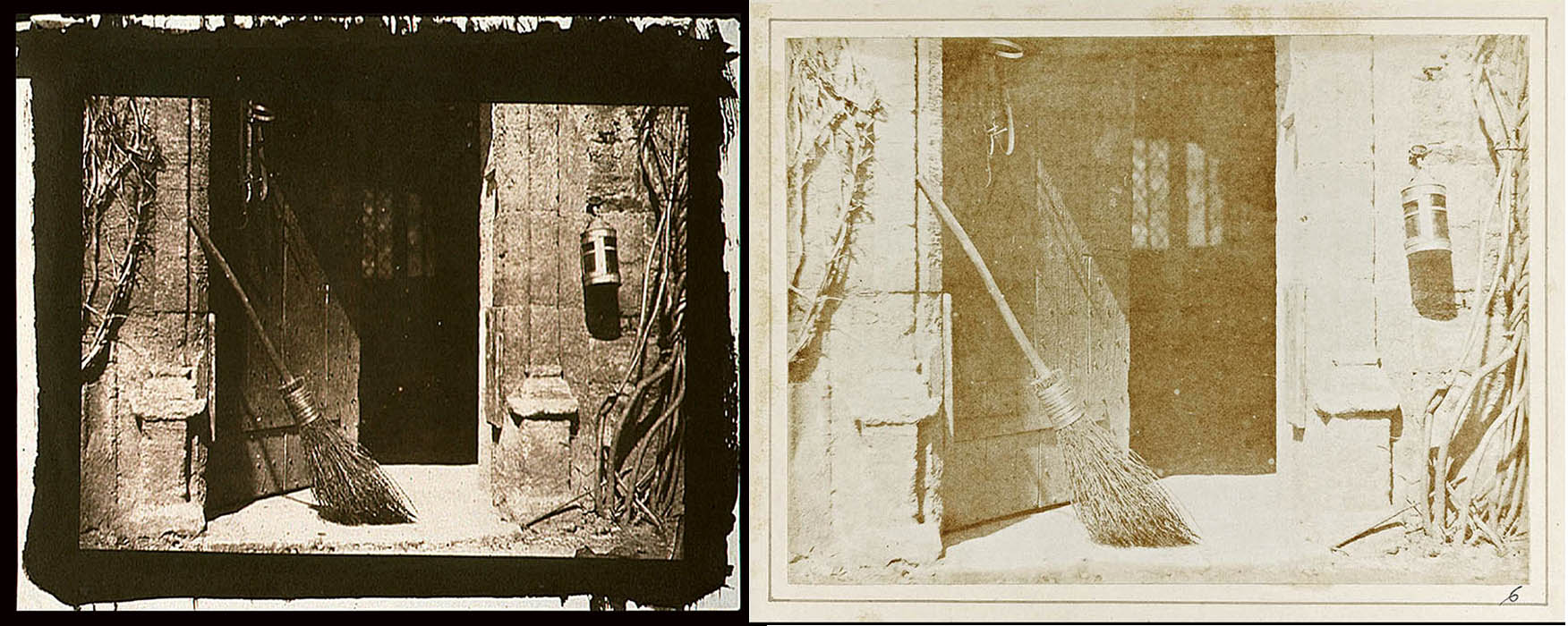

As we have discussed before, a major cause of the collapse of Talbot’s pioneering Pencil of Nature publication was the unexpected instability of the prints once they ventured forth into the real world. When a print was properly made, fixed in fresh chemicals and fully washed it was off to a good start. The untrimmed example on the left was probably kept in a drawer or a portfolio for much of its early life and has come down to us today with apparently the same vigour as when it was made. The print on the right probably started out looking just like the one on the left. Perhaps it was washed less well, perhaps the fixer was exhausted by the time this print hit it, but potentially the most destructive turn came when it was mounted onto a board and bound into a published copy of The Pencil of Nature. Once there it faced a host of hostile forces, including the micro-climate of the boards and the binding, the interaction with other prints within its binding, and the coal-smoke laden atmosphere in which it likely spent its early life. Equally critically, since it was in a book rather than a desk drawer, the temptation was to look at it, often in brightly sunlit rooms.

I won’t repeat here the old joke that to get three different opinions on conservation you need to ask two conservators, but the generally accepted wisdom is that either of these can be safely exhibited today under carefully controlled conditions. A strong print like the one on the left can probably withstand low light levels in controlled humidity and temperature under modern light conditions for any reasonable length of exhibition. Less certain is the vulnerability of the print on the right, but many would agree that time and the elements have taken their toll and that it is now in a relatively stable state.

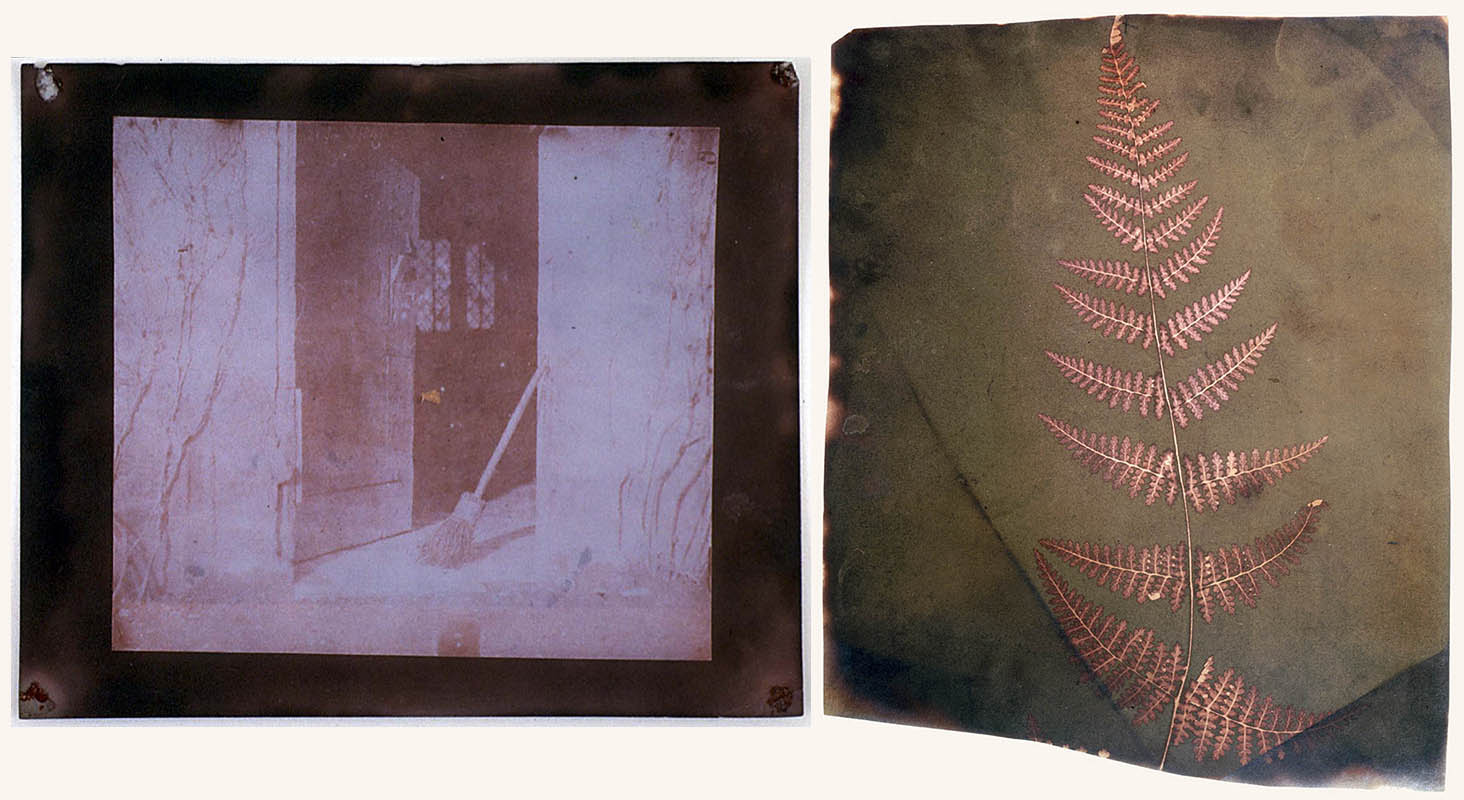

Now, personally I think that it is a miracle that we can see any image left after 175 or so years, but photographs like the above pose a problem. A halide-stabilized print like The Soliloquy of the Broom on the left retains light-sensitive chemicals in its makeup. Even though fairly strong, we can reasonably expect that any exhibition risks damaging it. The lovely fern on the right is an even more miraculous survivor. Whatever practise may have been in the past, it should never be considered for exhibition. Bill Hillman courageously chose to add these to his collection, recognizing a responsibility to protect them for future generations. But what was Dan Leers to do for his exhibition? To hang these would been irresponsible, no matter how low the lighting nor carefully controlled the conditions. But what does one owe to the public? You cannot excise these from the timeline of history, nor should you deprive the public of the experience of seeing them that a few privileged individuals might have had.

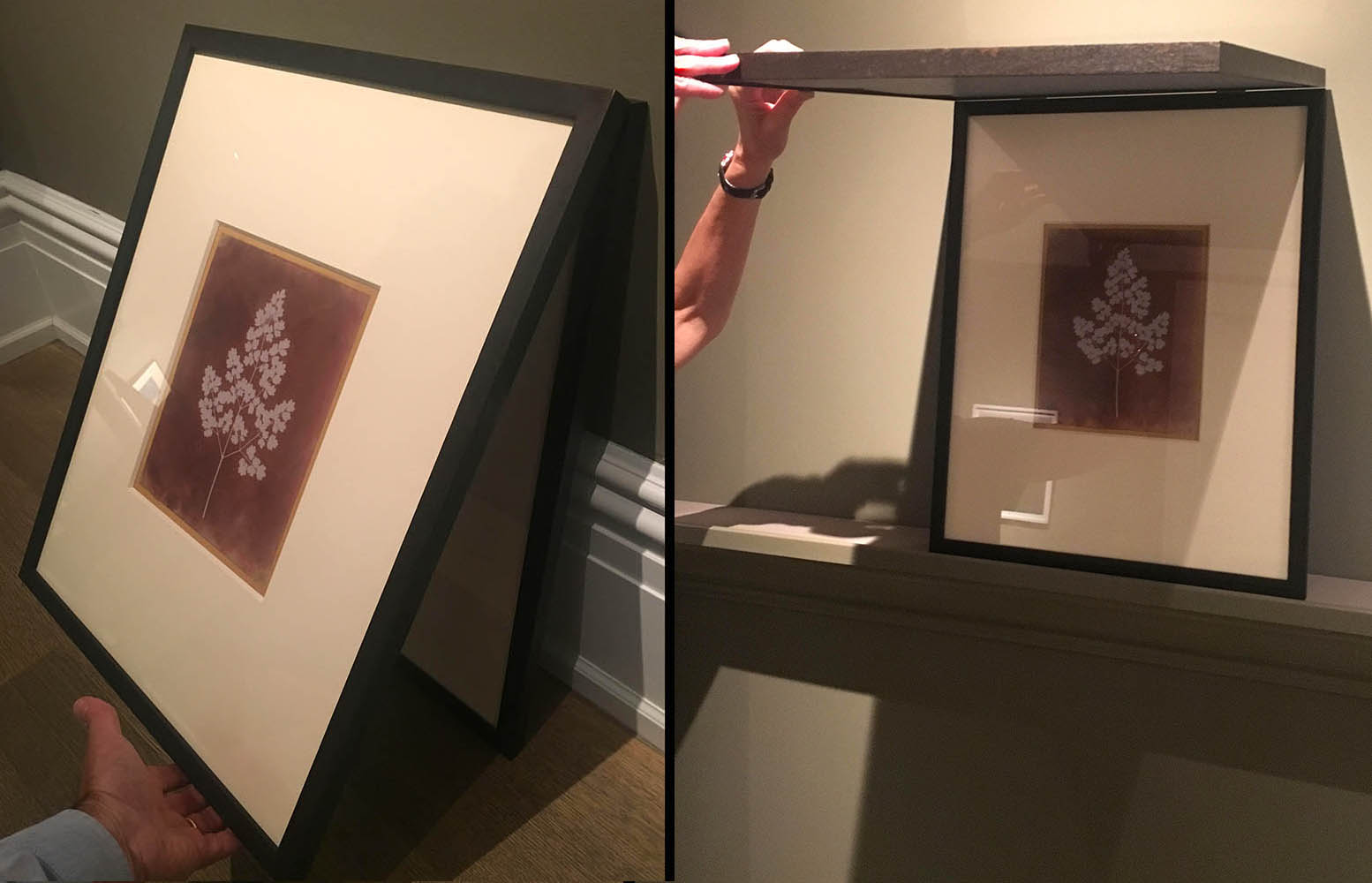

And that is where the Fayum comes in. Once these originals are taken off display the Museum will want to make them available responsibly to bonafide researchers. The Kraus gallery pioneered a special type of framing that addresses many of these concerns. An exacting facsimile is mounted in an outer frame and can be used for preliminary assessment of the image. When it becomes necessary to examine the actual object, the frame can be lifted to reveal the original. The accuracy and any shortcomings of the facsimile can be immediately judged by expert comparison.

These specially framed pieces minimize handling of the original while allowing full examination. They should not be used for public exhibition, of course, but they are an approach to be considered in archival settings.

I want to finish by returning to William Talbott Hillman. Fair disclosure, it was his insight and the backing of his Foundation that made this Catalogue Raisonné possible. It was his perceptive collecting that made possible the current exhibition at the Carnegie. And it was his family’s long history of philanthropy that prepared him to offer his precious Talbots to the permanent collection of the Carnegie Museum of Art. As a result, Pittsburgh is now a regional powerhouse in Talbot studies.

As a photographer, one of William T Hillman’s projects has been a serious of massive photograms, echoing what Henry Talbot produced many decades before – Bill once told that he had “tried to respectfully push that other William’s venerable and essential discovery and legacy forward.” In his photographs, his collecting, and his philanthropy, Mr Hillman is accomplishing that. By the way, the above might not seem so striking on your monitor (or even less so on your tiny phone screen), but Hillman’s photogram is nearly four meters long, about 135 times the surface area of Talbot’s!

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Attributed to Nicolaas Henneman, Part of Queens College, Oxford, calotype negative, ca. 1844, William T Hillman Collection, the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Schaaf 1584. • Installation photographs by Bryan Conley, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art. • WHFT, The Open Door (two variants), salted paper prints from a calotype negative, April 1844, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, New York; Schaaf 2772 and Schaaf 2821. • WHFT, The Soliloquy of the Broom, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 21 January 1841, Private Collection, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, New York; Schaaf 2541. • WHFT, Buckler Fern, photogenic drawing negative, 1839, William T Hillman Collection, the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Schaaf 154. • For an excellent understanding of Talbot’s challenges with fixers, consult Dr Mike Ware’s Mechanisms of Image Deterioration in Early Photographs: the sensitivity to light of W.H.F. Talbot’s halide-fixed images 1834-1844 (London: Science Museum, 1994). • Mummy with an Inserted Panel Portrait of a Youth, Roman Period, A.D. 80–100, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acc. 11.139. • Hinged frame photographs courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, New York, Fine Photographs. • William T Hillman, Sweet Blessing, three panel photogram, 2001, 77 x 141 inches = 196 x 358 cm. The numerous Hillman Family Foundations support a wide range of cultural and other activities. A good understanding of the values of philanthropy can be gained in the story of the matriarch of the family, Elsie Hillman, in Never a Spectator.