Here in Baltimore this week, the near-frost conditions of the last day of April have miraculously morphed into the warmth of May. We should celebrate that with some of Henry Talbot’s photographs. But first, two of our Research Affiliates have filled our pages the past three weeks with fascinating studies of their respective home towns of Paris and Oxford. Last week, Édouard de Saint-Ours responded to some of the feedback he had received on his two previous posts. I don’t know if Simon Murison-Bowie has had lawyerly training, but he pointed to this as a precedent for supplementing his last. Both gentlemen have added greatly to our understanding of certain categories of Talbot’s photographs, so I am more than happy to yield the stage.

Place and time

My post last week about ‘’An Ancient Door” drew attention to the fact that my approximation had the wrong kind of shadow. With the helpful guidance of Dr Charlotte Berry, archivist at Magdalen College, and her assistant Ben Taylor, I have found out that there were indeed substantial changes to the Porters’ Lodge—the building that casts the shadow—in the mid-1880s, as part of the substantial new building programme that resulted in St Swithin’s Quad. This extended the College to the west, taking in all the land along the High Street up to Long Wall Street. A ‘casualty’ of this development, so described in the 1000+ pages of Magdalen College, Oxford: A History published by the College in 2008, was the gate designed by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin.

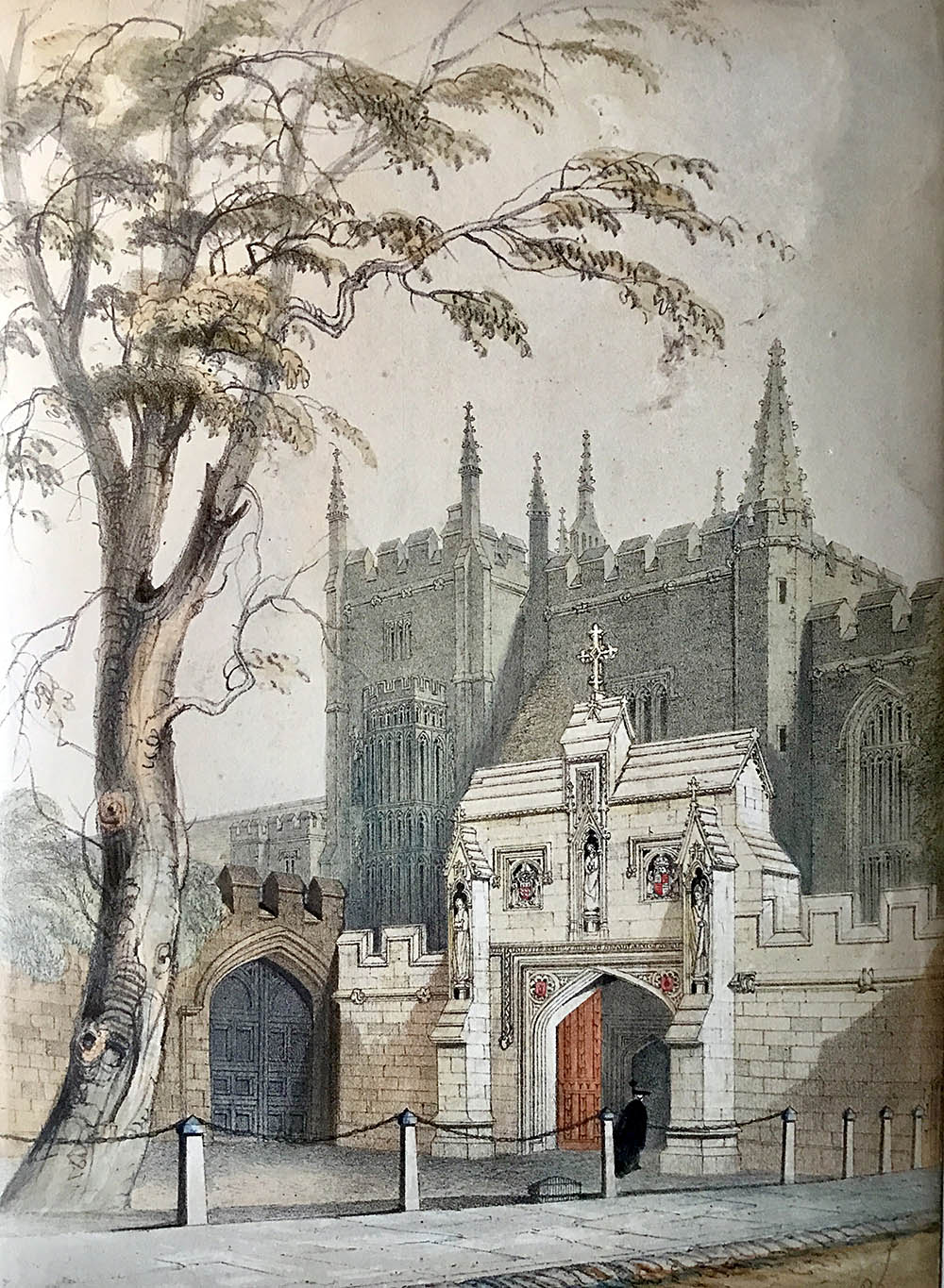

This was the gate photographed by Talbot: ‘New Entrance Gate, Magdalen College, Oxford’:

Pugin (1812–1852), designer of many neo-gothic churches, the interior of the Palace of Westminster and of the Elizabeth Tower (better known as Big Ben) was a friend of John Bloxam, a Fellow of Magdalen. He was responsible for Pugin’s gate commission. From our point of view there are two matters to consider: the position of the gate and its date of completion.

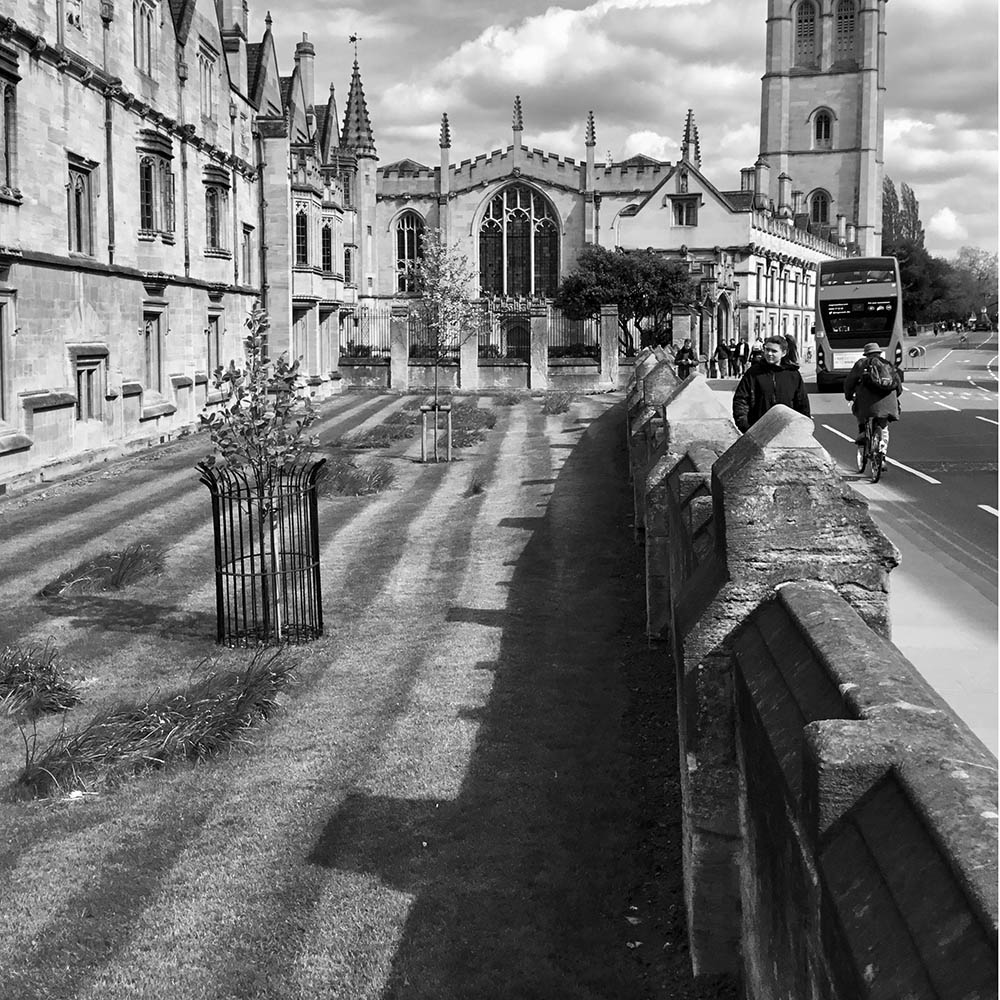

The first is easier to deal with. In the 1840s the main entrance to the College faced west (or rather NNW) towards the city centre and was approached by the ‘Gravel Walk’ that ran parallel to the High Street. It would have been approximately in the centre of the pillars and the railings at the end of the lawn in this photograph.

The reason why the gate was a casualty of the new building in the early to mid-1880s was because the architects Bodley and Garner decided the entrance should be repositioned to where it is now, facing directly on to the High Street, a gateway they designed. Pugin’s gate was demolished there are some fragments from the gate preserved at the base of the Great Tower—two statues (John the Baptist and S. Mary the Virgin) and two shields (according to a plaque on the wall of London and Exeter). All four pieces come from the inside of the gate (an image of which has not been found) and do not therefore appear in either the engraving or Talbot’s photograph.

An understanding of this earlier positioning of the gate and of how it was approached explains the very different backgrounds in Talbot’s photograph and in the Bodley and Garner gate photographed today. It also explains why a convincing approximation of Talbot’s ‘High Street, Oxford’ is impossible today.

The date of the erection of Pugin’s gate is significant in that it could enable us to date Talbot’s photograph. Larry has shared with me a 2012 exchange of emails he had with Dr Robin Darwall-Smith, then archivist of Magdalen—now at University College, where he has been very helpful to me. Larry cites Litvack’s “An Auspicious Alliance: Pugin, Bloxam, and the Magdalen Commissions” ‘in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, v. 49 no. 2, June 1990, pp. 154-160. He claims the gateway was assembled in August 1844, from components constructed in London’. The Magdalen College archives present a , though not necessarily contradictory view. Robin Darwall-Smith records that the agreement for the construction of the gate wasn’t signed until April 1844. Robin continues: ‘We also have several letters here from Pugin to John Bloxam … [that] … show that he is still discussing the final details of the gate even in July 1844. Then on 8 September 1844 he writes to Bloxam saying that “I am very anxious to see you & inspect the progress of the gateway”. In November he is writing to Bloxam to say that he thinks that the images for the gateway will be “very good”, that the shields are finished and that “in a month all will be compleat [sic]”. Belcher adds a note here that on 12 December Pugin visited Oxford and wrote in his diary “Gateway finished”. Going back to the papers in our archives on the gate, I see that Pugin was still settling bills for it until December 1845. I have also seen a minute from a meeting of the Building Committee that suggests that it was only in December that they finally agreed to the design. Does Pugin’s statement that ‘it is finished’ mean that the planning business is finished and that finally the construction can go ahead? Despite the various assertions that the gate dates from 1844 (including the aforementioned plaque on the wall in the Great Tower), everything else points towards a structure completed in 1845 and that being the date of HT’s photograph. But when in 1845? We know from the correspondence that he was in Oxford in January 1845 but that would have been too early for the gate to have been completed. I have no evidence of a later visit. The search goes on …

Simon Murison-Bowie

And now, a quick look at the first four days in May, as seen through Henry’s eyes

1 May 1840

Three Statuettes sunning themselves on the Lawn of Lacock Abbey

2 May 1843

Nicolaas Henneman

3 May 1840

basket under a larch, Lacock Abbey

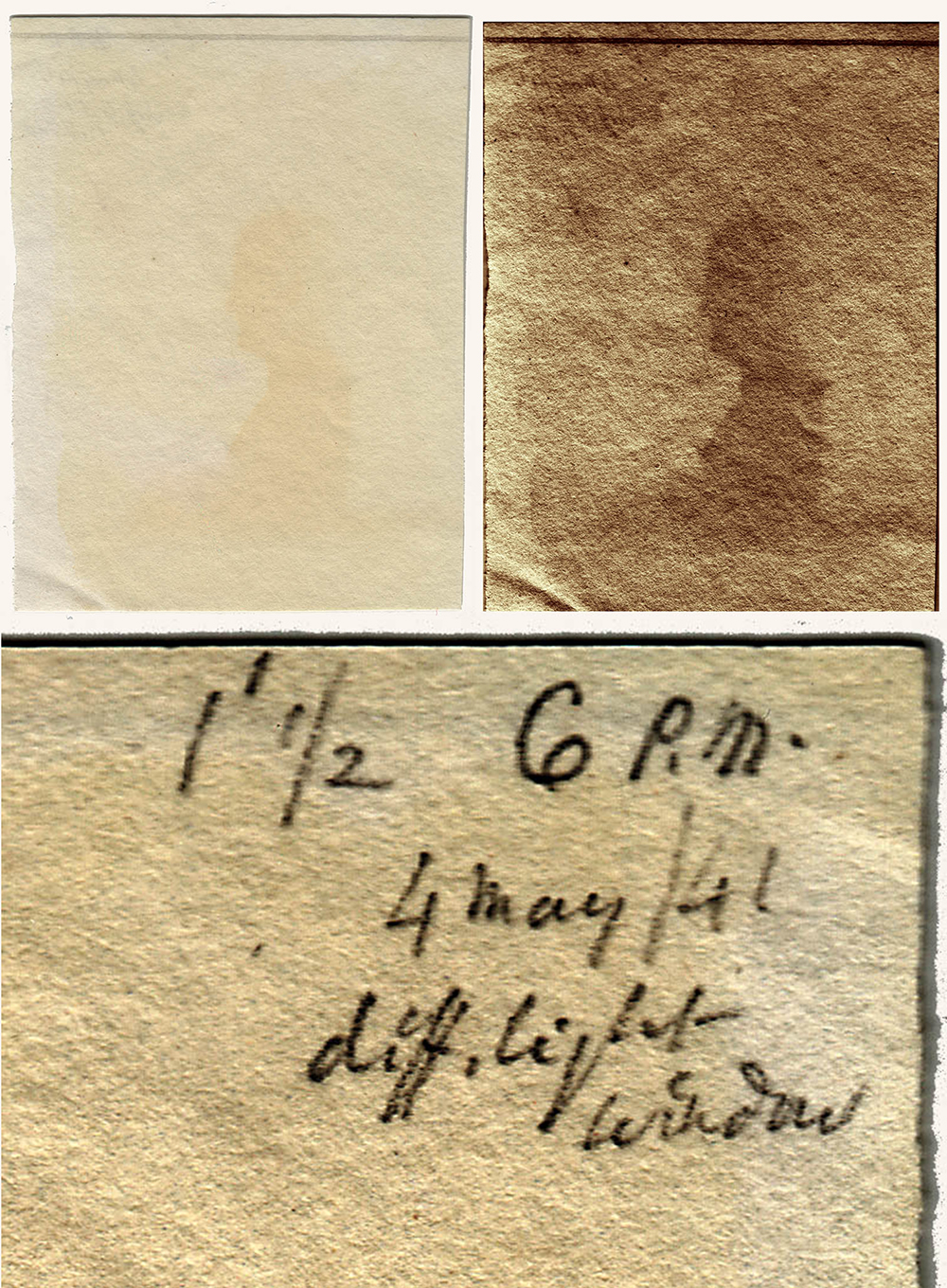

4 May 1841

experimental negative of a silhouetted bust

The negative is largely faded so it is presented here with an augmented version. Talbot inscribed on the verso that he took this with a minute and a half exposure at 6 pm on 4 May 1841, using diffused light from a window. The calotype process was less than a year old and this was around the time that his patent was granted – perhaps it was a demonstration of the extraordinary powers of the new negative process.

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • The New Pugin Gate at Magdalen College, Oxford, etching by an unidentified artist. This and the photographs of the fragments in the Great Tower are reproduced here by kind permission of the President and Fellows of Magdalen College (the photographs of the fragments were viewed by appointment and are not on public display). • WHFT or Rev Calvert R Jones, The New Pugin Gate at Magdalen College, Oxford, salted paper print from a calotype negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1709-1; Schaaf 1443. • WHFT, The New Pugin Gate at Magdalen College, Oxford, salted paper print from a calotype negative, Private Collection, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, NY; Schaaf 3572. • WHFT, The High Street, Oxford, salted paper print from a calotype negative, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2005.100.73; Schaaf 1005. • WHFT, Three Statuettes on the Lawn at Lacock Abbey, salted paper print from a photogenic drawing negative, 1 May 1840, British Library, London, LA2249, Schaaf 2415. • WHFT, Nicolaas Henneman, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 2 May 1843, Art Institute of Chicago, 1975-1055: Schaaf 2725. • WHFT, Basket Under a Larch Tree, salted paper print from a photogenic drawing negative, 3 May 1840, British Library, London, LA2288, Schaaf 3839. • WHFT, Silhouette of a Bust, calotype negative with pencil inscription on verso, 4 May 1841, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1995-206-222; Schaaf 2596.