It is certainly confusing that there is a photoLondon and a Photo London. Although one died recently, Lazarus-like it has just been resuscitated. The second is a relative youngster, but is alive and well and is hosting a fascinating Talbot reincarnation next week.

But first, on this day in 1792, John Frederick William Herschel was born. Henry Talbot met him for the first time in Munich in 1824 (although to be fair, Herschel spent his time then talking to Lady Elisabeth and Captain Feilding, recalling only that he met their son, “A Cambridge man”). But the two men first became regular correspondents and eventually close collaborators. Herschel was thirty-seven when this miniature was painted. So, happy 226th birthday, Sir John – we’ll have to do a blog on you some day.

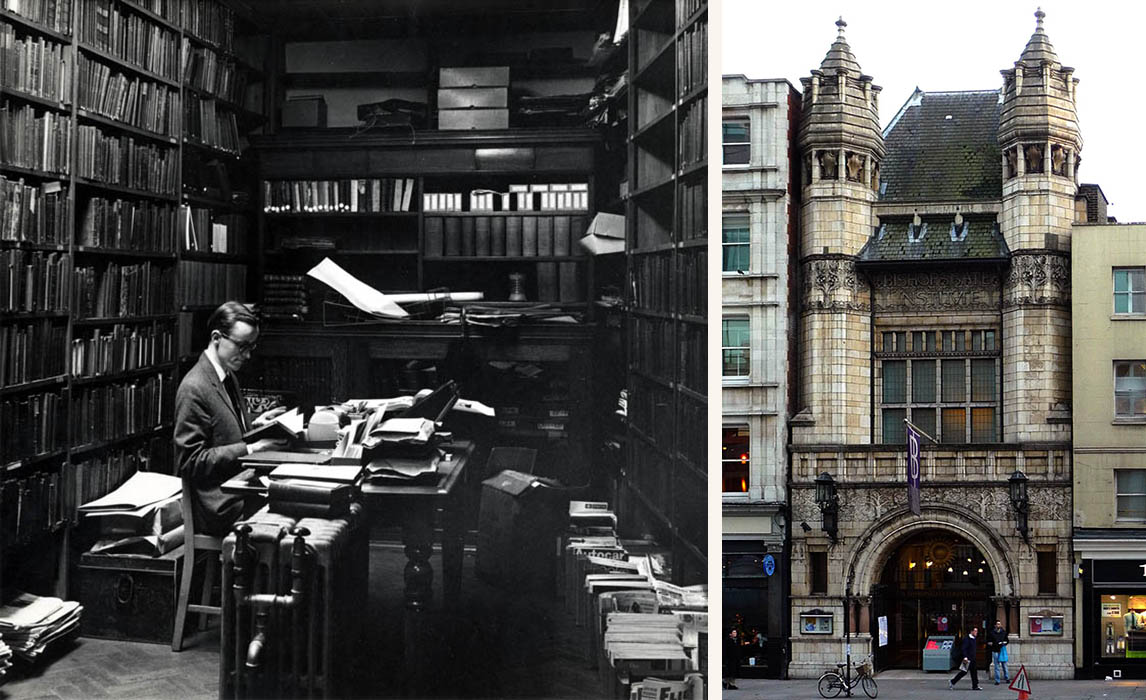

Especially in the internet age, one person’s passion can give a huge helping hand to untold researchers. Sadly, just before Christmas, David Richard Webb passed away at the age of eighty. For many years he was the ‘go-to’ librarian of the Bishopsgate Institute, a marvelously preserved building near the Liverpool Street Station in London. The building is far more than a visual treat, for it embodies the spirit of free education for the public which started in the mid-19th century. This concept was supported by hard-hearted capitalists such as Andrew Carnegie and George Peabody, philanthropic not only because they personally felt that it was the right thing to do, but more importantly because they believed that society (as well as their own pockets in the long run) would be enriched by a better-educated and better-informed populace. Why have we wandered off that perceptive path today? But I digress. Amongst some photohistorians, David’s work was legendary, for he worked up detailed reports on more than 8500 photographers who based themselves in London and freely published this in his alphabetised photoLondon.

David had studied languages at Oxford and was an avid historian of East London. He was fully comfortable in genealogical sources and this talent for detail shows in his entries.

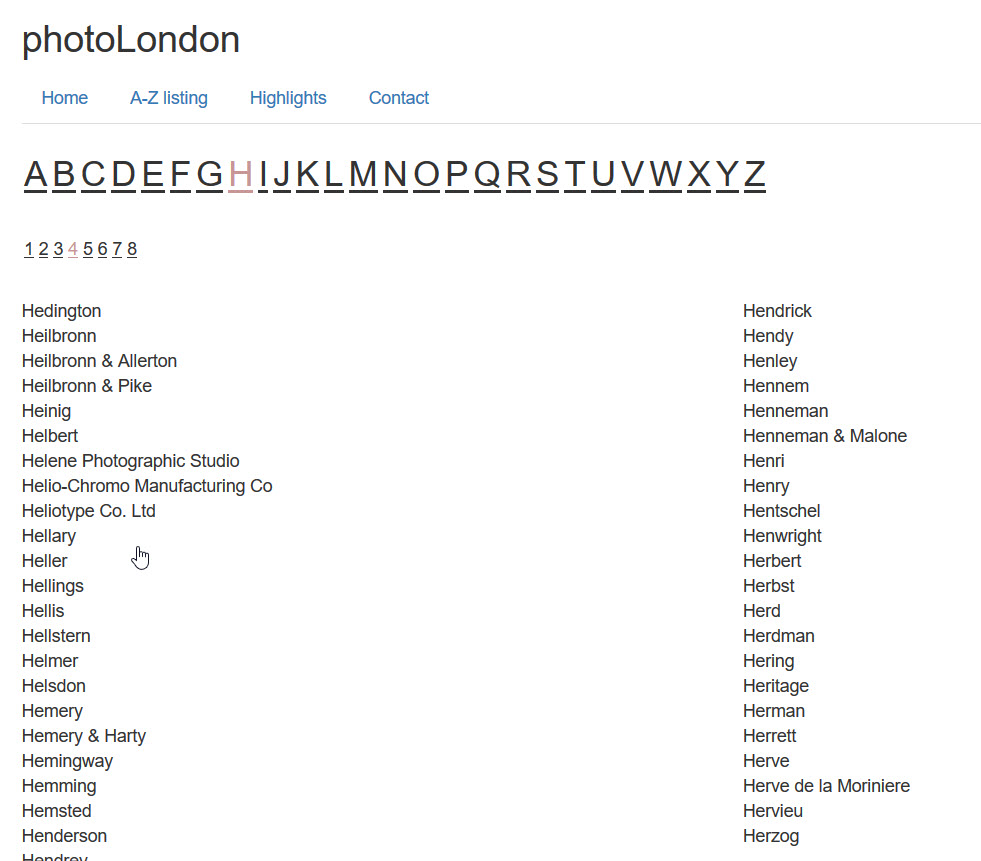

Using this list, or the search mechanism, you could bring up details on a wide range of people who contributed to photography in London in the 19th century, not only photographers, but their assistants and their suppliers and in some cases their distributors.

We never got to debate the proper spelling of Nicolaas’s name but otherwise it is this type of detailed information compiled by David that was so valuable. You can see that the information gathered goes beyond the bounds of London, for David included as much as he could find on the previous and subsequent careers of the photographers, wherever that may have been.

Perhaps some of my readers will recall card catalogues and printed encyclopedias and will be familiar with the concept of serendipity (egged on by poor discipline) where you always looked at the cards before and after your quarry or the pages adjacent in the encyclopedia just to see what was there. David’s alphabetical listing encouraged that – how else would I have known to look into the work of Charles Stanley Herve de Morinaire?

Like many individual-driven projects, this site went down from time to time – just like the Talbot Correspondence Project with its more than 10,000 Talbot letters has teetered on the brink many a time (and is not out of the woods yet). English Heritage’s National Monuments Record (now more or less Historic England) first hosted the site and when they found this no longer possible the Museum of London picked it up. But like the Correspondence and many other projects, David’s work was preserved in an increasingly-archaic digital file structure. I can wander into the Bodleian and within minutes (if I had the language skills) be reading a 14th century manuscript, but as many of you know, that stuff on your ten year old floppy disks may no longer be readable at all. Late last year, around the time of David’s death, the site went dark, itself the victim of old age.

Michael Pritchard and the regular readers of his British Photographic History site (and you are one of them, aren’t you?) immediately took up the cause for many of us were literally left in the dark by this loss. Happily, David Lowe had previously captured many (but not all) of the entries for his fascinating New York Public Library site – Photographer’s Idenity Catalog, something that partially filled the gap, but David Lowe even lamented his previously too-enthusiastic winnowing of the data.

The King is Dead! Long Live the King! I am happy to report that thanks to the efforts of Michael and especially of Anna Sparham, curator at the Museum of London, Lazarus-like the site has been brought back to life. The search mechanism has yet to be revived, but the alphabetical listing is back in all its glory. My personal thanks to everyone who was involved in bringing David’s legacy back to life. If you haven’t been using it (but after completing reading this blog), head over to photoLondon and do some fishing.

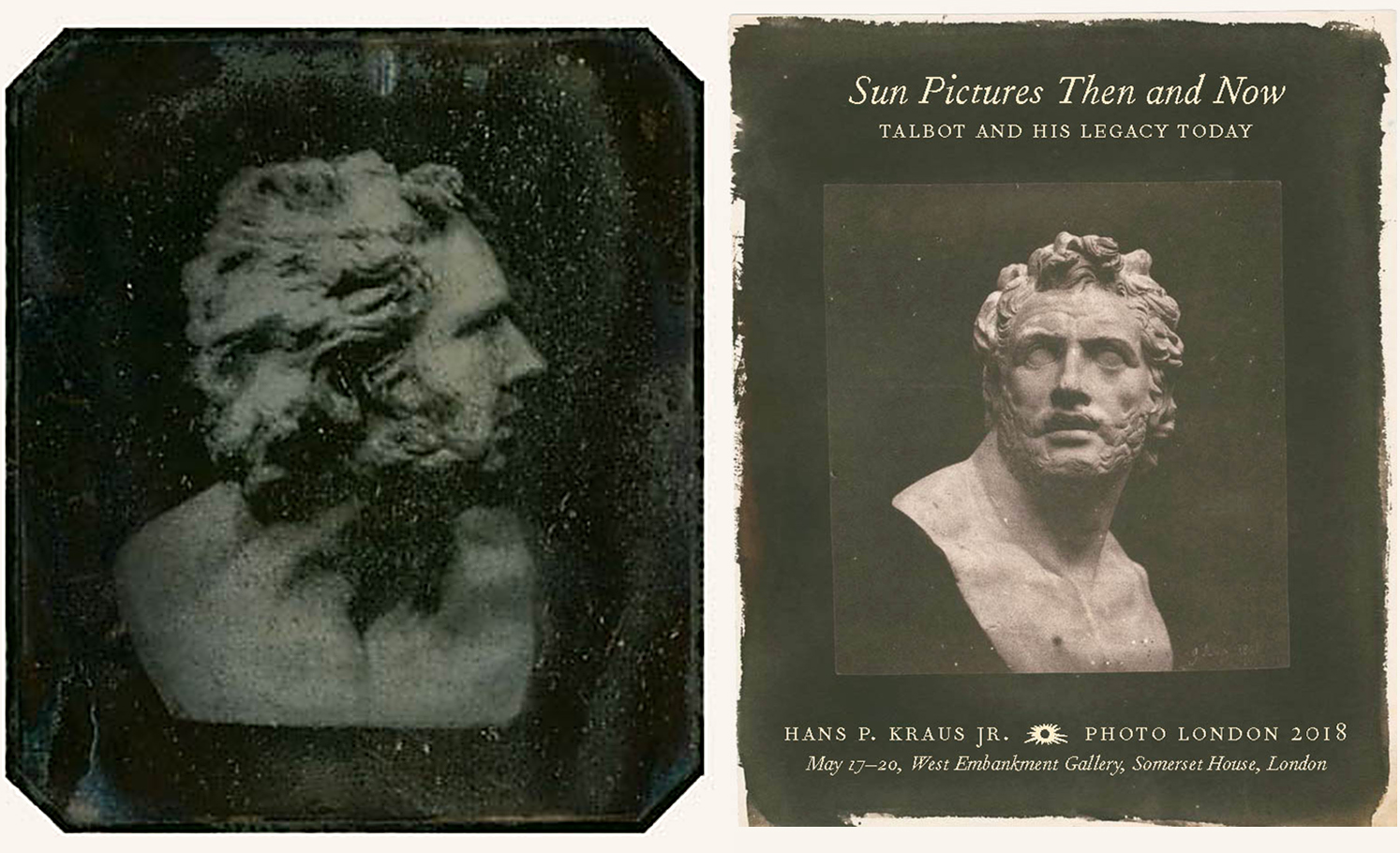

Near the end of a previous posting, I mentioned the special exhibition that is going to be held at the other Photo London, this one the sprawling international photographic fair that will be held at Somerset House in London for the too-brief period of Thursday 17 May through Sunday 20 May. It was within these rooms that Talbot’s first paper on photography was read before the Royal Society on 31 January 1839. And now, 179 years later, Henry is making a big return visit. The New York gallery of Hans P. Kraus, Jr., Inc. is mounting a very special exhibition that you should see if at all possible. Sun Pictures Then and Now: Talbot and His Legacy Today has been curated by Mr. Kraus himself. One aspect of it will be a very significant showing of rarely exhibited Talbot originals, more than thirty in number, along with other Talbot artefacts, mostly drawn from Kraus’s own holdings. These originals will be played against a series of works by contemporary artists who have reacted viscerally to Talbot’s originals. If there is any way for you to get to London next week, it is an exhibition that should not be missed.

I showed some of Grant Romer’s ‘Io-types’ in a previous post and at least some of these will be on display – although nobody knows how they will morph over the course of several days of exposure. Known as a daguerreotypist, conservator and phrenologist, Grant has also contributed an io-type Talbotroclus to this exhibition.

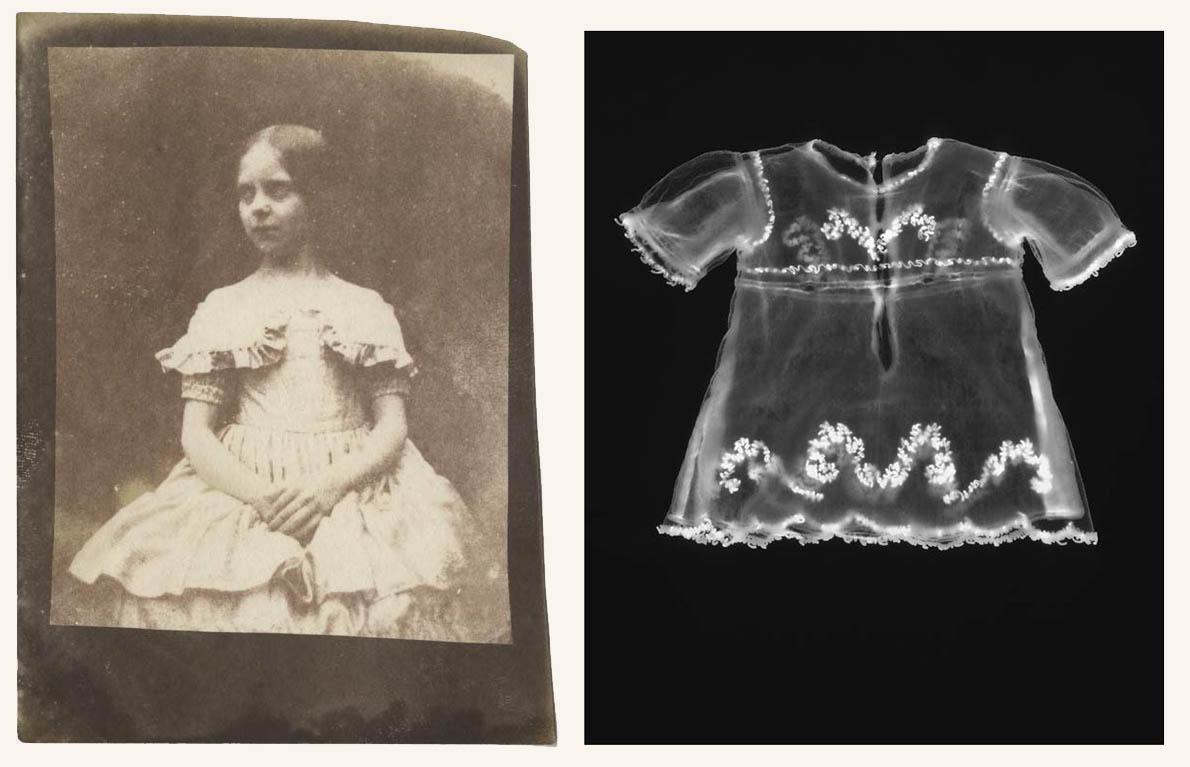

WHFT, The photographer’s daughter, Ela Theresa Talbot, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 1843–1844; Schaaf 4610. Adam Fuss, from the series My Ghost, silver gelatin photogram, 1997. Adam took his first series of pinhole camera images in 1984 and this led him to explore camera-less photographic techniques. Much of his work is now centred on daguerreotypes and photograms.

WHFT, The photographer’s daughter, Ela Theresa Talbot, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 1843–1844; Schaaf 4610. Adam Fuss, from the series My Ghost, silver gelatin photogram, 1997. Adam took his first series of pinhole camera images in 1984 and this led him to explore camera-less photographic techniques. Much of his work is now centred on daguerreotypes and photograms.

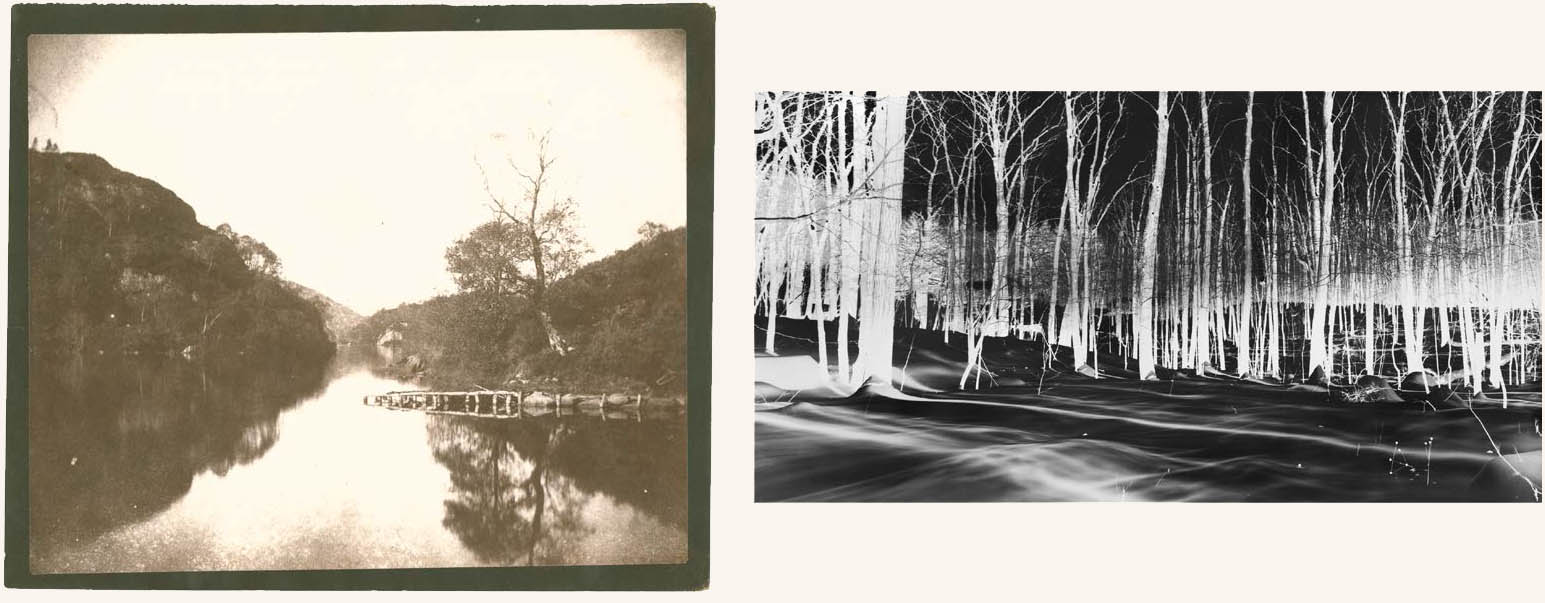

WHFT, Loch Katrine, salted paper from a calotype negative, October 1844; Schaaf 2787. Vera Lutter, Cold Spring, IX, 17 February 2014, unique gelatin silver negative. Lutter’s negative is more than twelve times as long as Talbot’s image and nearly a hundred times the surface area.

WHFT, Loch Katrine, salted paper from a calotype negative, October 1844; Schaaf 2787. Vera Lutter, Cold Spring, IX, 17 February 2014, unique gelatin silver negative. Lutter’s negative is more than twelve times as long as Talbot’s image and nearly a hundred times the surface area.

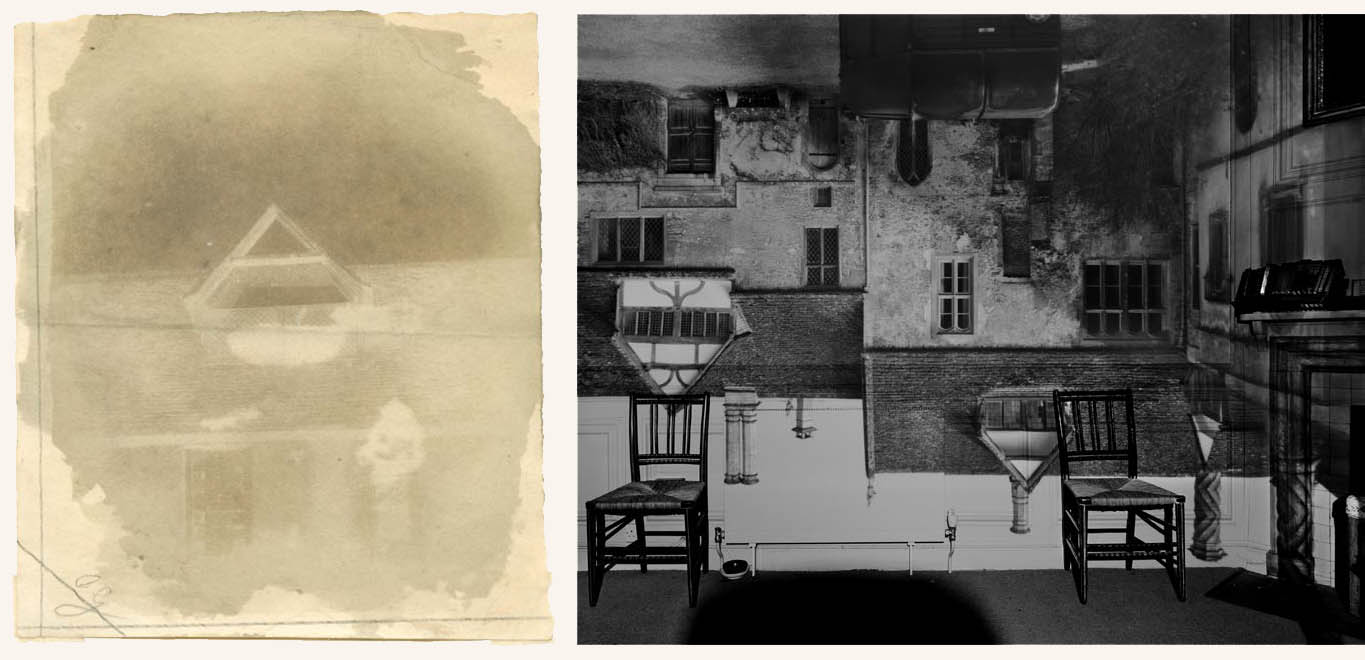

WHFT, Dormer window inside the Cloisters of Lacock Abbey, calotype negative, most likely 1842; Schaaf 3392. Abelardo Morell, Courtyard Building, Lacock Abbey, pigment print from a camera obscura projection, 2003. Abe blacks off a room and then sets a lens in a small opening in a window, forming a camera obscura image which he then photographs on film. One wonders if Talbot himself accidentally observed such an effect from an imperfectly closed shutter, either providing part of his inspiration for conceiving of photography, or something that he observed for the first time after he started working with his new art.

WHFT, Dormer window inside the Cloisters of Lacock Abbey, calotype negative, most likely 1842; Schaaf 3392. Abelardo Morell, Courtyard Building, Lacock Abbey, pigment print from a camera obscura projection, 2003. Abe blacks off a room and then sets a lens in a small opening in a window, forming a camera obscura image which he then photographs on film. One wonders if Talbot himself accidentally observed such an effect from an imperfectly closed shutter, either providing part of his inspiration for conceiving of photography, or something that he observed for the first time after he started working with his new art.

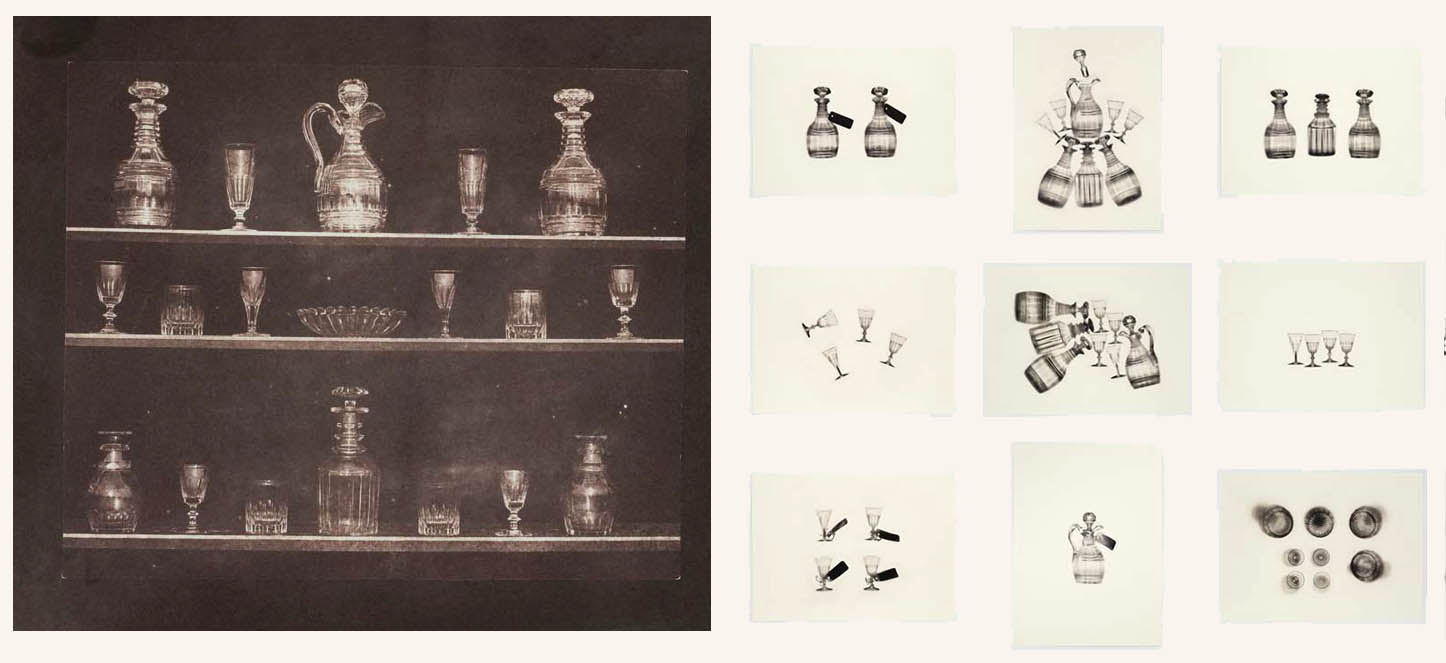

WHFT, Articles of Glass, salted paper print from a calotype negative ; Schaaf 69. Cornelia Parker, Fox Talbot’s Articles of Glass, Set of 9 polymer photogravure etchings, 2017. The Bodleian Library loaned this glassware originally from Lacock Abbey to the artist (did I ever drink out of one when staying at Lacock Abbey?). Some of these original glasses had previously been displayed in the Bodleian Library and two of them will be in this exhibit.

WHFT, Elm tree in winter, in the grounds of Lacock Abbey, calotype negative, 13 February 1843; Schaaf 2706. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Talbotized 013, gelatin silver print, 2012. Sugimoto collects original Talbot negatives, sometimes employing them directly in his photographs, sometimes drawing inspiration from them. Some time ago he borrowed Talbot’s electrical discharge wand in order to make some of his images, including this one. That wand, on loan from the Bodleian Library, will be on display in this exhibit.

WHFT, Elm tree in winter, in the grounds of Lacock Abbey, calotype negative, 13 February 1843; Schaaf 2706. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Talbotized 013, gelatin silver print, 2012. Sugimoto collects original Talbot negatives, sometimes employing them directly in his photographs, sometimes drawing inspiration from them. Some time ago he borrowed Talbot’s electrical discharge wand in order to make some of his images, including this one. That wand, on loan from the Bodleian Library, will be on display in this exhibit.

WHFT, South Terrace at Lacock Abbey, waxed salted paper print from a calotype negative, 1842–1843; Schaaf 1113. Mike Robinson, Lacock Abbey, Sharington’s Tower, half-plate daguerreotype, 2015. A premier daguerreotypist, scholar and teacher, Mike will be running a daguerreotype workshop at Lacock Abbey in June and another outside Rome at the conservation studio of our Advisory Board Member, Sandra Maria Petrillo. Mike’s thesis, The Techniques and Material Aesthetics of the Daguerreotype, is the most intensive and up to date treatise on the subject and can be read here.

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Alfred E Chalon, John Herschel, miniature painting, 1829; Herschel-Shorland Archive. • Adam Fuss courtesy of Cheim & Read, New York. • Vera Lutter courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, New York. • Abelardo Morell courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York & Zürich. • Cornelia Parker courtesy of Alan Cristea Gallery, London. • Hiroshi Sugimoto courtesy of Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo. • WHFT’s daughter and glass courtesy of the Wilson Centre for Photography, London.