This week’s guest author is Ann Compton, who has published extensively on sculpture and British art. Her idea, to develop and deliver an online resource dedicated to British sculpture, resulted in the wonderful ‘Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951’.

This week’s guest author is Ann Compton, who has published extensively on sculpture and British art. Her idea, to develop and deliver an online resource dedicated to British sculpture, resulted in the wonderful ‘Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951’.

Ann has been incredibly helpful in regard to many of the lesser-known sculptures and statuettes that were the quarries of Henry.s camera. Most of these sculptural works remained unidentified until Ann cast her expert eye over Talbot’s photographs of them, and for that we thank her. Today she gives us some added insight into one of those pieces, and why Talbot might have taken the time and trouble to photograph it.

Brian Liddy

Guest post by Ann Compton

Guest post by Ann Compton

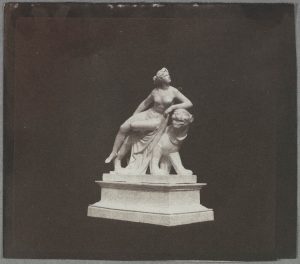

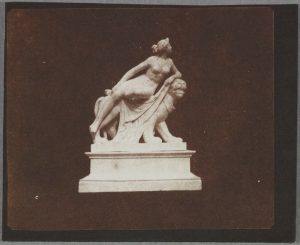

In 1812, Henry first wrote his mother about the Greek tale of Ariadne, describing his current readings at Harrow. In Greek mythology, Ariadne was the daughter of Pasiphae and granddaughter of the sun god Helios. She played a pivotal role in the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. On 10 December 1845, Constance Talbot wrote to her husband to say she would ‘touch up the Ariadne & send them back to you tomorrow.’ This is the first known reference to Talbot’s multiple photographs of Johann Heinrich von Dannecker’s (1758–1841) celebrated sculpture, Ariadne on a Panther (1803–1814).

While Constance’s work on these photographic prints provides a useful fixed point, we cannot be sure that all of the thirty-one surviving images of this work (comprising 24 prints and 7 negatives) were completed by December 1845. Nor can we rule out the possibility that Talbot was printing up negatives made at an earlier date. But whatever the exact chronology for their production, this exchange of letters tells us that Henry was printing from calotypes of Ariadne on a Panther during the same period he was publishing The Pencil of Nature (published between 24 June 1844 and before 23 April 1846) and Sun Pictures in Scotland (1845). Since both of these ambitious projects were highly demanding and presented several ultimately insuperable technical challenges, the timing of work on Ariadne on a Panther invites speculation.

Indeed, it raises the intriguing possibility that as Talbot ruminated on how many more instalments of The Pencil of Nature would be issued, he was evaluating Ariadne on a Panther as a potential subject even though this work does not appear in the list of potential future plates. Certainly, the inclusion of an alternative to Patroclus, famously the only sculpture Talbot in the end featured, would have added weight to his remark in the text accompanying plate 5, that ‘statues, busts, and other specimens of sculpture, are generally well represented by the Photographic Art.’ Out of the large number of sculptures Henry ultimately photographed (more than seventy-five are documented in the Catalogue Raisonné), there are many reasons why Ariadne on a Panther would have been given serious consideration.

In the first half of the nineteenth century this statue was one of the most famous sculptures in Europe, and by far and away the most celebrated work by a German sculptor. The statue had been bought by Simon Moritz von Bethmann, a wealthy banker, for his private museum in Frankfurt from Johann Heinrich von Dannecker’s studio in 1814. Following the end of the Napoleonic wars there was a rapid expansion in European travel, and over the next forty years the statue of Ariadne became one of the most popular destinations for tourists visiting Frankfurt. The statue’s fame spread to Britain via Murray’s and Baedecker’s guidebooks, and attracted many famous writers, artists, and politicians, including Benjamin Disraeli, Mary Shelley, and George Eliot, as well as numerous anonymous visitors.

We can be sure Talbot was aware of these developments because his favourite uncle, William Fox Strangways (later 4th Earl of Ilchester), held the position of Britain’s Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the German Confederation in Frankfurt between 1840-49. Strangways’ diplomatic posting meant he entertained numerous distinguished visitors to the city, and as an art collector himself, would certainly have directed guests to the Bethmann museum. Strangways also hosted visits from many members of the family including Henry, who spent a few days in the city in March 1842, and Henrietta Gaisford (Talbot’s half-sister) who had passed through the previous summer. These particular visits are mentioned here because around this time interest in the Ariadne was further intensified by the news of Johann Heinrich von Dannecker’s death on 8 December 1841.

However, it would not just have been these familial connections to Frankfurt which directed Talbot’s attention to this famous sculpture. Long before this he was tuned into the larger currents in sculptural practice and, particularly, the prime importance of Italy for artists and collectors. This is evident in his correspondence from the 1820s onwards, and later through his decision to photograph works by some of the most prominent European sculptors who had lived in Rome at the turn of the century, including Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828), Antonio Canova (1757-1822), and Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844).

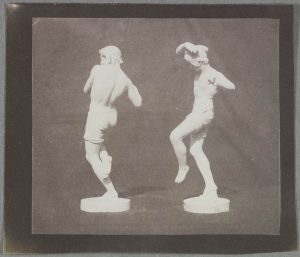

Talbot was also aware that Italy remained important to the careers of younger artists like Francisque Jospeh Duret (1804-1865) who achieved fame in the 1830s with his bronze statuettes of dancing Neapolitan fishermen (1833 and 1838). These inspired the ever-inventive Denis Pellerin to construct Talbot anaglyphs.

Dannecker belongs firmly within this group, having joined Antonio Canova’s circle of friends during his studies in Paris, Rome, Bologna and Mantua between 1780 and 1790. Henry’s appreciation of the attractions of Rome and mythological subjects for sculptors meshed with his own precocious interest in the classics. Indeed, at the age of twelve, the youthful Talbot listed ‘Ariadne abandoned by Theseus on the desert island, found by Bacch’, the very subject of Dannecker’s sculpture, as one of the tales he was studying at Harrow.

While Talbot’s awareness of Europe’s cultural landscape merely affirms what might be expected of someone of his class and education, it is notable that several of the works he chose to photograph were renowned for the setting in which the originals were displayed. This is true, for example, of Canova’s Three Graces, which the sculptor presented on a turntable so that the viewer could easily experience the work in all its dimensions, and was later sited by the 6th Duke of Bedford in a specially designed Temple of the Graces at Woburn Abbey. The use of carefully staged techniques to present Ariadne on a Panther were also well-known.

While Talbot’s awareness of Europe’s cultural landscape merely affirms what might be expected of someone of his class and education, it is notable that several of the works he chose to photograph were renowned for the setting in which the originals were displayed. This is true, for example, of Canova’s Three Graces, which the sculptor presented on a turntable so that the viewer could easily experience the work in all its dimensions, and was later sited by the 6th Duke of Bedford in a specially designed Temple of the Graces at Woburn Abbey. The use of carefully staged techniques to present Ariadne on a Panther were also well-known.

In 1814, when Dannecker sold the sculpture to Bethmann he hoped the sculpture would be displayed on a turntable (as his friend Canova had done with the Three Graces). Bethmann did not implement this request but he did pay some attention to the artist’s other wish, which was to install a red curtain near the Ariadne so that the marble would be bathed in a warm reflected light. The pink glow, which suffused the nymph and her panther, was an important part of the visitor’s experience at the museum in Frankfurt. Some considered it a great success, while others, like Anna Jameson, the Irish author of many widely circulated books on art and artists, judged the roseate hue a kind of trickery that interfered with the purity of marble as a sculptural medium.

We do not have a direct record of Henry’s thoughts on this subject but its setting offers an obvious dialogue with his commentary on plate 5 of Patroclus in The Pencil of Nature. Here Talbot directs his reader, whose vision as a proponent of the photographer’s art is assumed to be particularly keen, to the relationship between the viewer and the work, and to the subtle interplay between the materials and the technique of lighting. He particularly dwells on the unlimited variety of ‘delineations’ offered by turning a three-dimensional object through three hundred and sixty-five degrees. Talbot also discusses the different effects of the angle of the sun’s rays on our perception of form, and offers specific advice about taking photographs of sculpture on a cloudy day and using a white cloth to reflect a gentle light onto the work. In other words, the issues Henry urged novice photographers to address in the practice of photographing sculpture were broadly the same as those addressed by the artist in the presentation and appreciation of the Ariadne.

Where we step on to less secure ground (a puzzle that surrounds many of Talbot’s photographs of sculpture) is where where Henry sourced the version of Ariadne on a Panther that he used to make these images. It is true we can be pretty certain he was working from a reduced scale copy after the original because during Dannecker’s lifetime there was an embargo on making full-scale replicas. There is a small possibility that the version Talbot photographed was made from marble or alabaster, since both materials were often used for reproducing such prestigious works as Ariadne, but it is more likely that he had access to a plaster copy. We know from some surviving reproductive plaster casts that belonged to Talbot, and from several photographs showing groups of statuettes arranged on shelves or ornamental brackets that this was his common practice.

Working from plaster casts offered a number of obvious advantages to the photographer. Gypsum’s comparative lightness as a sculptural material allowed him to move objects around, and leave them outside in the light until an exposure had been made. Talbot evidently valued the whiteness of plaster because works in this medium were more adaptable to different light conditions (an attribute that artists also valued). For these reasons, even if his uncle had been able to secure permission to photograph the original Ariadne at the Bethmann museum, Henry would have declined the opportunity because, the interior setting would not have suited his needs. Also, the rose-coloured light bathing Ariadne would not have suited the calotype process which was more sensitive to light from the blue end of the spectrum.

Looking back on all the reasons for photographing Dannecker’s sculpture, we might conclude that the memorialisation of the most famous work of a recently deceased artist was Talbot’s principal motivation. However, it was soon apparent that Dannecker’s death was not the start of a decline in interest. In 1847, two years after Constance was busy touching up her husband’s prints, the Minton factory created statuettes of the Ariadne in Parian ware. This recently developed material was a highly vitrified porcelain with a finish intended to imitate statuary in marble. Parian was an instant success, and so great was the anticipated demand for ceramic statuettes of ‘Ariadne on a Panther‘ that Minton reproduced the work in two different sizes. These works were modelled after the originals by the British sculptor, John Bell, who was also commissioned to make a companion composition entitled Una and the Lion. Minton’s Parian reproductions of the ‘Aridane‘ remained in production for nearly twenty years and copies were acquired by Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort for the Royal Collection. This was not the only attempt to bring Ariadne on a Panther to a London audience. Between October and December 1849 Madame Duval presented a tableaux vivant at the Minerva Hall on the Haymarket, which featured ‘a celebrated German artiste’ on an accurate model of a panther with novel red light effects.

Quite what Talbot would have made of this theatrical re-presentation of a modern sculpture we can only guess. But even if he dismissed it as merely popular entertainment, he would doubtless have been pleased to hear that the organisers of the Great Exhibition attempted to borrow the original marble from the Bethmann museum in 1851. Indeed all of this activity makes it clear that Talbot’s photographs of Dannecker’s work were extremely well timed, and may even have helped stimulate this fresh wave of interest in an iconic sculpture.

Ann Compton

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Constance Talbot to WHFT, 10 December 1845, The British Library, London, Doc. No. 5461. • Constance Talbot to WHFT, 18 December 1845, The British Library, London, Doc. No. 5484. • WHFT, The Reading Establishment, two salted paper prints forming a panorama, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2005.100.171.1, Schaaf 1595, and 2005.100.171.2, Schaaf 1596. • WHFT, Statuette of Ariadne and the Panther, after Heinrich Dannecker, Calotype negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2809, Schaaf 1764. • Johanna Roethe, ‘Dannecker’s Ariadne: from Neoclassical Temple to Victorian Mantelpiece’, Sculpture Journal, 26(2), pp. 141-158 • WHFT, Statuette of “Ariadne and the Panther”, after Heinrich Dannecker, salted paper print, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2794/3, Schaaf 1763. • WHFT, Two Statuettes of “Dancing Fishermen” after Francisque-Joseph Duret, salted paper print, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2841/2, Schaaf 2030. • WHFT, Two Statuettes of “Dancing Fishermen” after Francisque-Joseph Duret, salted paper print, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2840/1, Schaaf 2031. • WHFT to Elisabeth Theresa Feilding, 27 January 1812, The British Library, London, Doc. No. 555. • WHFT, Statuette of “The Three Graces” after Antonio Canova, salted paper print, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2013.159.59, Schaaf 1844. • David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, Mrs. Anna Jameson, carbon print, 1843-47, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, (gift of the Edinburgh Photographic Society Collection), PGP-EPS-288 • WHFT, Two Statuettes of “Dancing Fishermen” after Duret with “Statuette of Ariadne and the Panther” after Dannecker, four Calotype negatives printed on a single salted paper print, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2841, No Schaaf number. • WHFT, Eight Classical statuette on sculpted brackets, salted paper print, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2847, Schaaf 814. • After John Bell, Ariadne and the Panther, Parian-Ware, 1847-69, Royal Collection Trust, RCIN-52319 • The online resource, Mapping the Practice and profession of Sculpture in Britain & Ireland 1851-1951 was conceived and developed by Ann Compton around the same time as another important online scholarly resource, The Correspondence of William Henry Fox Talbot. Both of these sites were created at a time before the internet was image friendly (or as ravenous for images as it is now). Both websites are highly recommended and well worth a visit.