Now that the days are shorter, and the nights are drawing in, it is time to put the Summer Pleasure posts away and return to larger portions about Talbot and his work. Perhaps this is the blog equivalent of moving from summer salads to autumnal comfort food. Our first big helping of the season comes from Professor Geoffrey Batchen. In this post, Geoff’s third contribution to the Talbot project blog, he discusses a French photographer better known for his daguerreotypes, Antoine François Jean Claudet. This week we learn about Claudet’s photographs on paper, and his business relationship with Talbot. How did they get on? Over to you, Geoff.

Now that the days are shorter, and the nights are drawing in, it is time to put the Summer Pleasure posts away and return to larger portions about Talbot and his work. Perhaps this is the blog equivalent of moving from summer salads to autumnal comfort food. Our first big helping of the season comes from Professor Geoffrey Batchen. In this post, Geoff’s third contribution to the Talbot project blog, he discusses a French photographer better known for his daguerreotypes, Antoine François Jean Claudet. This week we learn about Claudet’s photographs on paper, and his business relationship with Talbot. How did they get on? Over to you, Geoff.

Brian Liddy

Guest post by Geoffrey Batchen

Guest post by Geoffrey Batchen

A number of professional photographers approached Talbot in the 1840s about the possibility of purchasing a license to practice calotypy. Of those, Antoine Claudet may have been the most accomplished.

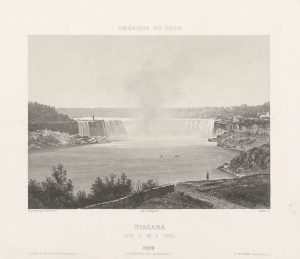

Born in France, Claudet moved to London in 1827 to establish a retail outlet for imported French glass sheets and glass ware. He soon became co-proprietor of ‘Claudet and Houghton,’ a shop at 89 High Holborn. By 1840, that shop was selling copies of the first six fascicles of Lerebours’s Excursions Daguerriennes as well as a number of daguerreotypes made for it.

Always interested in scientific discoveries, Claudet was present at the announcement of the details of Talbot’s calotype process on 10 June 1841 at a meeting of the Royal Society. In that same month Claudet opened his own daguerreotype studio in the Royal Gallery of Practical Science, or Adelaide Gallery, as it was known. Claudet soon approached Talbot about the possibility of making calotype portraits too. But Claudet was already familiar to Talbot, even before they first met. In a letter to John Herschel dated July 1, 1841, Talbot had issued an imaginary challenge to the Frenchman: “It is a nice point to determine which is the most sensitive to light, my Calotype paper, or the Daguerreotype improved by Claudet’s process. I am sensitive to simple moonlight; he has not yet made the trial, which I throw out as a challenge to all photographers of the present day: viz. that I grow dark in moonlight before they do.” Whether or not he ever heard this challenge direct from the calotype’s inventor, five years later, in March 1846, Claudet sought to meet it by making the first daguerreotype image generated by contact printing.

SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERIES. The London correspondent of the Boston Atlas, describing a scientific soiree, says:

What seems to cause the greatest astonishment, is an impression of black lace upon a daguerreotype plate, by the light of the stars! M. Claudet, in referring to this phenomenon, observed, that he considered it as proof of the chemical power of star-light. He said that he had prepared a plate in the usual manner, covered it with a piece of black lace, and exposed it to the then brightest part of the sky, the constellation Ursa Major, nearly at the zenith. It was left to the influence of these, and the surrounding stars, for about fifteen minutes, which sufficed to impress the black lace upon the plate [Footnote 1].

Whereas Beard’s letters to Talbot are formal and focus on questions of business, the tone of Claudet’s correspondence is quite different. Beginning in January 1842 and continuing until Claudet’s death, he and Talbot regularly exchanged sometimes-lengthy letters. The Frenchman almost always wrote in his native language—the language of both science and diplomacy, but also a choice that signaled a shared level of education. They corresponded, in other words, as peers. Their earliest exchanges concerned an electrotype facsimile process that Claudet was experimenting with, apparently again to make a copy of a daguerreotype of lace

By August 1842, Claudet was buying a camera (“Goudin’s model”) from Lerebours on Talbot’s behalf. In October, after a visit by Talbot to Claudet’s studio, they began to more seriously negotiate a licensing arrangement, with Claudet quite sensibly pointing out that “1/3 of the takings would be far more than 3/4 of the profits,” suggesting instead that Talbot be satisfied with “1/3 of the net profits.” More impressive than Claudet’s business acumen might have been the addition of this sentence, carefully calculated to appeal to any anxious inventor: “I assure you that I would devote myself to it wholeheartedly, and that your invention would receive the honour it deserves.

By August 1842, Claudet was buying a camera (“Goudin’s model”) from Lerebours on Talbot’s behalf. In October, after a visit by Talbot to Claudet’s studio, they began to more seriously negotiate a licensing arrangement, with Claudet quite sensibly pointing out that “1/3 of the takings would be far more than 3/4 of the profits,” suggesting instead that Talbot be satisfied with “1/3 of the net profits.” More impressive than Claudet’s business acumen might have been the addition of this sentence, carefully calculated to appeal to any anxious inventor: “I assure you that I would devote myself to it wholeheartedly, and that your invention would receive the honour it deserves.

Subsequent letters discuss further details, with Claudet pointing out, for example, that his daguerreotype studio costs included “between £8 and £10 for newspaper advertisements” per week, an acknowledgement that a photography studio’s viability depended on constant promotion as well as demonstrated technical expertise. Some of these letters were sent by Claudet from Paris, a frequent destination in 1842, 1843 and 1844. In one he offers to examine (and if possible procure) examples of the direct positive paper photographs of Hippolyte Bayard, one of Talbot’s potential rivals, and to try and ascertain the best possible paper for use in the calotype process (various samples of which he goes on to test and describe in detail).

Claudet also showed some of Talbot’s own photographs to his French colleagues. By December 1842 they “are virtually in agreement” on a contract, but this agreement proved to be a mirage, as they were still in fact haggling politely over details in January 1844. This despite Claudet’s assurance, in a letter dated January 18, 1843, that “I have written to Mr. Keates, my principal assistant at the Adelaide Gallery that you have granted me the right to use the Calotype procedure & I have given him the order to begin to carry out tests in order to familiarize himself with the procedure.” It’s a reminder that many of the photographs being issued by “Claudet” in these years were in fact being made in his absence by assistants.

By January of 1844, the situation had changed. Although Talbot and Claudet continued to negotiate terms, Talbot could now recommend that the Frenchman hire his “late” assistant Nicolaas Henneman to give him “full instructions in the art.” Talbot’s mother also seems to have been involved in the discussions, as evidenced by a letter she sent to Talbot on 13 September 1844: “I hope you are thinking of some arrangement by which Nicole [Nicolaas Henneman] can spend a Month chez Claudet on your return from Belgium. Claudet having the stimulus of his own interest will spread your Fame by his success.”

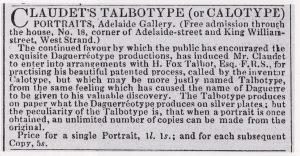

Despite the inability of Henneman to make a profit from calotypy, Claudet diligently went about mastering the process with a view to offering it as an option to his customers. A typically grandiose advertisement appeared in the Athenaeum of 6 July 1844 to inform the public that Claudet had entered into “arrangements with H. Fox Talbot, Esq. F.R.S, for practicing his beautiful patented process, called by the inventor Calotype, but which may be more justly named Talbotype, from the same feeling which has caused the name of Daguerre to be given to his valuable discovery.”

No wonder that Lady Elisabeth, always keen that her son brand his invention with his own name, was so fond of Claudet! As she told Talbot in a letter dated 7 April 1844: “I hope Claudet will see in the same light so many others do. a clear distinct name would be a positive benefit to the Art; Shakspear [sic] says what’s in a name? I answer a great deal, in modern times.” Based on references in his letters, Claudet took Talbot’s advice and sought not only the expert guidance of the calotype’s inventor but also the assistance of Henneman, Murray and Malone, all of whom also worked at one time at the Reading Establishment.

Despite constant efforts to improve the process, outlined in periodic reassuring letters to Talbot (“I took on the Talbotype with the intention of making it prosper & I will spare neither expense nor effort in achieving this aim. I would be ashamed if anyone could accuse me of the contrary”), Claudet was nevertheless unable to make a profit on it and soon returned to the daguerreotype as his primary portrait medium. As he explained to Talbot in a letter dated 24 August 1844:

Until we have succeeded in operating on a surface as even & as perfect as a silver plate, I will say that the Daguerreotype produces more delicate, better finished and more perfect images than the Talbotype. Until we have succeeded in making the Talbotype operate within a few seconds & as a quickly as the Daguerreotype, I will say that, in this respect, the Daguerreotype has an advantage when it comes to obtaining an acceptable impression. But I will also say that the Talbotype has charms which the other lacks, that the prints are more portable and can be circulated more easily, sent by post or put into albums &c.&c. Finally, an unlimited number of copies can be obtained, which is not possible with the Daguerreotype.

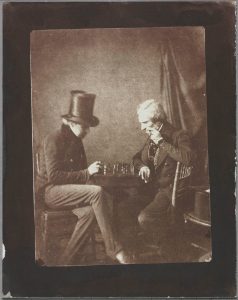

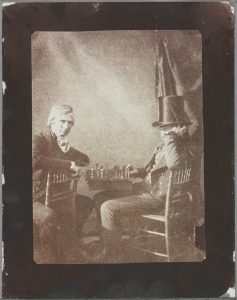

Despite his reservations, Claudet did continue to experiment with paper-based photography, finding it conducive to the making of a kind of picture he had long aspired to. As early as 17 July 1841, the Literary Gazette and Journal of the Belles Lettres had recorded that its reporter had seen “several good specimens” of daguerreotype group portraits at Claudet’s studio, including “players at the chess and lookers-on, company at table variously engaged, etc.” As Larry Schaaf has discussed in an earlier blog entry, Claudet was involved in the making of a number of calotype genre pictures of this same sort in collaboration with Henneman and Talbot in 1844 and 1845.

Talbot mentions one such collaboration in a letter to his mother dated April 18, 1845, telling her “Today I made a picture of a boy with a cage and a grey parrot at Claudet’s – It will make a very pretty tableau Flamand. The parrot sat beautifully, evidently understanding what we were doing.” The parrot, being stuffed, had no choice but to sit still, and did so uncomplainingly in a number of later interior daguerreotypes taken in Claudet’s studio. But Talbot’s reference to Flemish genre pictures is a reminder that this kind of art was in fashion in mid-nineteenth century Britain, a fashion that perhaps both Talbot and Claudet were keen to exploit.

A useful selection of Claudet’s calotype-based portraits, not many of which have survived, is to be found in a fascinating album of photographs put together by Calvert Jones in about 1844 [Footnote 2]. The album contains eleven photographs by Talbot, some of them photogenic drawings from 1839 and some of them later salt prints from calotype negatives, sixteen salt prints by Claudet, a few of them painted, and two early direct positive prints by Hippolyte Bayard, whom Jones had met in Paris on 30 July 1841. It therefore represents a joining of the two premiere inventors of paper-based photography, one English and the other French, literally linked in the pages of this album by the work of a man who was both. The images by Talbot range from a contact print of a piece of lace to a portrait of Henneman, basically covering his entire range of subjects. The two photographs by Bayard consist of a still life of plaster casts and a view over the rooftops of Paris. In other words, the album provides a comprehensive history of paper photography up to that point.

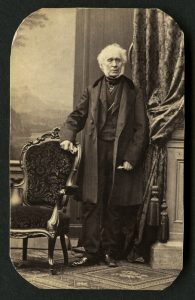

Claudet continued to run one of London’s premier photography studios until his death in 1867, always remaining in convivial contact with Talbot. In February 1862, for example, Claudet sent Talbot some glass positives to convert into photoglyphic engravings, including one derived from a carte-de-visite portrait of David Brewster. The year before he had written to Talbot to point out the commercial potential of this process: “I will be moved to see how the portraits which I sent you turn out with your engraving, because if there was a way to make them perfect with a little retouching, it would be of great importance for the sale of cartes de visite.”

Talbot did indeed produce a photoglyphic engraving of Claudet’s portrait of Brewster, with the Scotsman shown from a distance, standing in Claudet’s studio with his hand on a chair and beside a rectangular-based column, with a picturesque landscape painting on the wall behind him. Having invented paper-based photography, the system of representation that dominated the nineteenth century, Talbot now introduced photomechanical reproduction, which would similarly dominate the twentieth. And how fitting that, in this instance, two of his closest photographic allies, Antoine Claudet and David Brewster, should both be featured!

Notes

- This account comes from the Salem Gazette 65: 35 (1 May 1846), as transcribed in http://daguerre.org/resource/dagnews/05-01-96.html.

- See Sotheby’s Photographic Images and Related Material, London 14 April 1989, 44-49, and Larry Schaaf, Sun Pictures: Catalogue Five (New York: Hans Kraus Jr., 1990), 17-29.

Geoffrey Batchen

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, ‘The Chess Players’, salt print from a calotype negative, National Museum of Science and Media, Bradford, 1937-2526/16, Schaaf 2820 • WHFT, ‘The Chess Players’, salt print from a calotype negative, National Museum of Science and Media, Bradford, 1937-2527/8, Schaaf 2819 • H. L. Pattinson, ‘Niagara’, from Nöel-Marie-Paymal Lerebours, Excursions Daguerriennes. Vues et Monuments Les Plus Remarquables du Globe, aquatint after a daguerreotype of 1839, published Paris, 1840-42 • Gaudin daguerreotype camera made by Lerebours, courtesy of Christie’s, London. • ‘Claudet’s Talbotype (or Calotype)’, Advertisement, Athenaeum of 6 July 1844 • Antoine Claudet, Boy with parrot, about 1856, Hand-coloreud stereo daguerreotype, 84.XT.1566.11, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles • Antoine Claudet, Self-portrait, 1844, salt print from a calotype negative, mounted on album page 9, #101985.32, illustrated in Hans P. Kraus Jr., ‘Sun Pictures Catalogue Five’. • WHFT, Portrait of Nicolaas Henneman, 1840, salt print from a calotype negative, mounted on album page 7, #101985.27, illustrated in Hans P. Kraus Jr., ‘Sun Pictures Catalogue Five’, Schaaf 3681 • Studio of Antoine Claudet, London, Portrait of Sir David Brewster, carte de visite (albumen print on card), after 1851, courtesy of the Haast family, ref. PA2-0501, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand • WHFT (engraver), Sir David Brewster, 1862, photoglyphic engraving, ink on paper from a steel plate, from a carte de visite portrait by the studio of Antoine Claudet, London, Private Collection, image courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and Hans P. Kraus Jr., New York. • Larry Schaaf has attributed both versions of ‘The Chess Players’ to Claudet and Talbot, jointly. He surmises on the photographer in The Puzzling Chess Players. • Correspondence: The following letters were cited in by Geoff Batchen in the above blog, sometimes more than once. We’d like to take this opportunity to thank ‘The Correspondence of William Henry Fox Talbot’, at de Montfort University, Leicester, for their support. • WHFT to J. F. W. Herschel, 1 July 1841, Doc. No. 4293 • A.F.J. Claudet to WHFT, 4 January 1842, Doc. No. 4414 • A.F.J. Claudet to WHFT, 18 August 1842, Doc. No. 4581 • A.F.J. Claudet to WHFT, 7 October 1842, Doc. No. 4624 • A.F.J. Claudet to WHFT, 10 October 1842, Doc. No. 4626 • A.F.J. Claudet to WHFT, 19 November 1842, Doc. No. 4649 • A.F.J. Claudet to WHFT, 18 January 1843, Doc. No. 4700 • A.F.J. Claudet to WHFT, 24 December 1842, Doc. No. 4679 • A.F.J. Claudet to WHFT, 25 January 1844, Doc. No. 4922 • WHFT to A.F.J. Claudet, 22 January 1844, Doc. No. 4921 • Lady Elisabeth Feilding, Talbot’s mother, to her son, 13 September 1844, Doc. No. 5066 • Lady Elisabeth Feilding to her son, 8 April 1844, Doc. No. 4980 • N. Henneman to WHFT, 21 September 1844, Doc. No. 5078 • WHFT to A.F.J. Claudet, 22 November 1844, Doc. No. 8594 • A.F.J. Claudet to WHFT, 25 January 1844, Doc. No. 4922 • R. Calvert Jones to WHFT, 6 October 1845, Doc. No. 5404 • W.H. Wyndham-Quin to WHFT, 12 February 1844, Doc. No. 4938 • WHFT to his mother, Lady Elisabeth Feilding, 18 April 1845, Doc. No. 5231 • A.F.J. Claudet to WHFT, 14 January 1861, Doc. No. 8286.