I trust that you hoisted a wee dram this Wednesday to accompany your haggis at the Burn’s Night Supper. Wednesday was also the anniversary of Henry Talbot’s first public display of photographs on 25 January 1839. Struggling through the poor weather that summer and even more pathetic reception of the formal scientific community in Britain, he finally brought his photogenic drawings before the hundreds of serious amateur scientists at the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Birmingham in August. Rounding out the year was to be an ‘accidental’ exhibition in Edinburgh starting on Christmas Eve, eleven months after that initial showing. Within three years that city would witness the partnership of Robert Adamson with David Octavius Hill using Talbot’s process in an extraordinary expression of the photographic art.

Henry Talbot’s work had entered Scotland almost from the beginning through the channel of his enthusiastic colleague and close personal friend Sir David Brewster (yes, we must do a blog on him some day). Brewster had shown the photogenic drawings sent to him on a regular basis at local meetings in St Andrews and had shared them with colleagues throughout Scotland, but always in a private setting. The public had little chance to see what the fuss was all about.

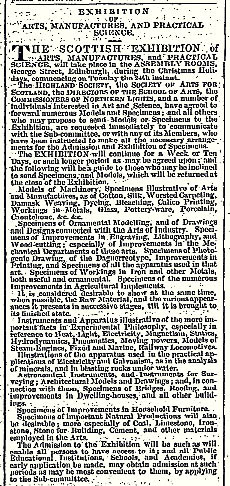

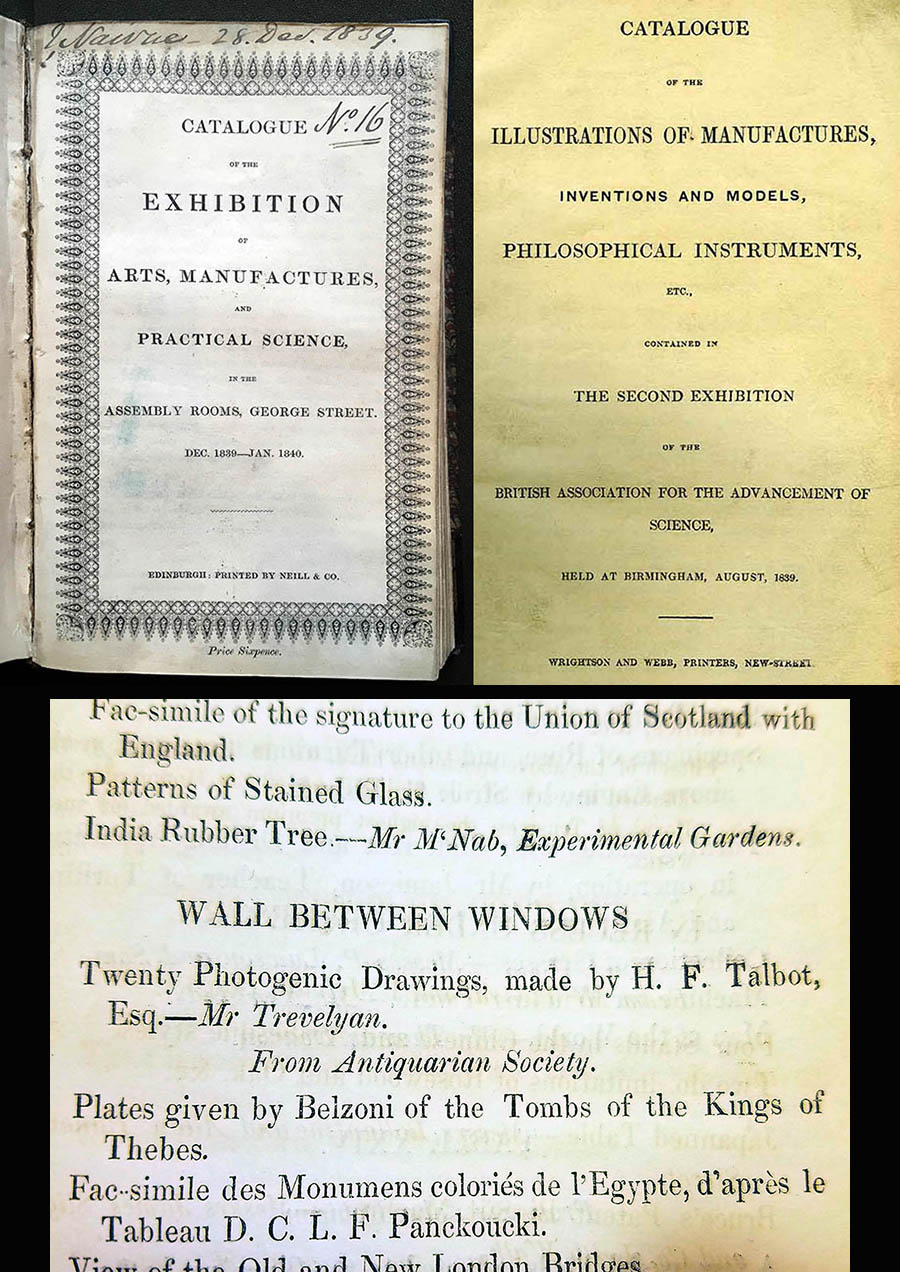

The chance to reach a wider audience came at the end of 1839, when Dr David Reid organised the Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Practical Science in Edinburgh. The twenty Talbot photogenic drawings hung on the walls had made their way up north from the Birmingham display. We have no way of knowing how many of the more than 50,000 visitors to this show stopped to examine the first fruits of Talbot’s magic but the opportunity was substantial. And it almost didn’t happen.

The Scotsman, 14 December 1839

One of Talbot’s oldest friends was Sir Walter Calverley Trevelyan (1797-1879), a geologist, naturalist and dour teetotaler. The two boys had attended Harrow School together in 1811, remaining friends into adult life, especially through a shared passion for botany. In 1835, Trevelyan had married Pauline Jermyn, a brilliant and outspoken much younger woman that fittingly he first met at a BAAS meeting. More on her in a moment. The Trevelyans had already seen photogenic drawings produced in Glasgow by Allen Machonochie but then Sir Walter received a 5 July 1839 letter from Talbot: “the other day your father & Dr Buckland favoured me with a call to see my photographs … I send you one as a specimen & if you would like to have any more I should have much pleasure in sending you a packet of them. The magnified images obtained by the Solar Microscope are particularly interesting.” The reply was immediate and enthusiastic for the “specimen of your photographs which I found here on my return a few days ago from a trip to the Highlands – it is one of the best I have yet seen. I am very much obliged to you for your offer of more & should much like to have a specimen of a view taken thro’ the Camera & of a magnified image if you have such to spare.”

But at the opening, he and Pauline noticed that something was missing from both the catalogue and the walls. The inventor of the art, their friend Henry Talbot, was not represented.

Sir Walter rectified this immediately. In his diary entry for Christmas Day, he proudly recorded that he “placed in the exhibition a number of Talbot’s Photogenic drawings.” In his diary entry for Christmas Day, he proudly recorded that he “placed in the exhibition a number of Talbot’s Photogenic drawings.” So unexpectedly high was the attendance for the exhibition that a second edition of the catalogue was rushed out – Talbot’s photogenic drawings were among the new entries included in this edition. A pdf of a more complete story about the Edinburgh exhibition is in the notes below.

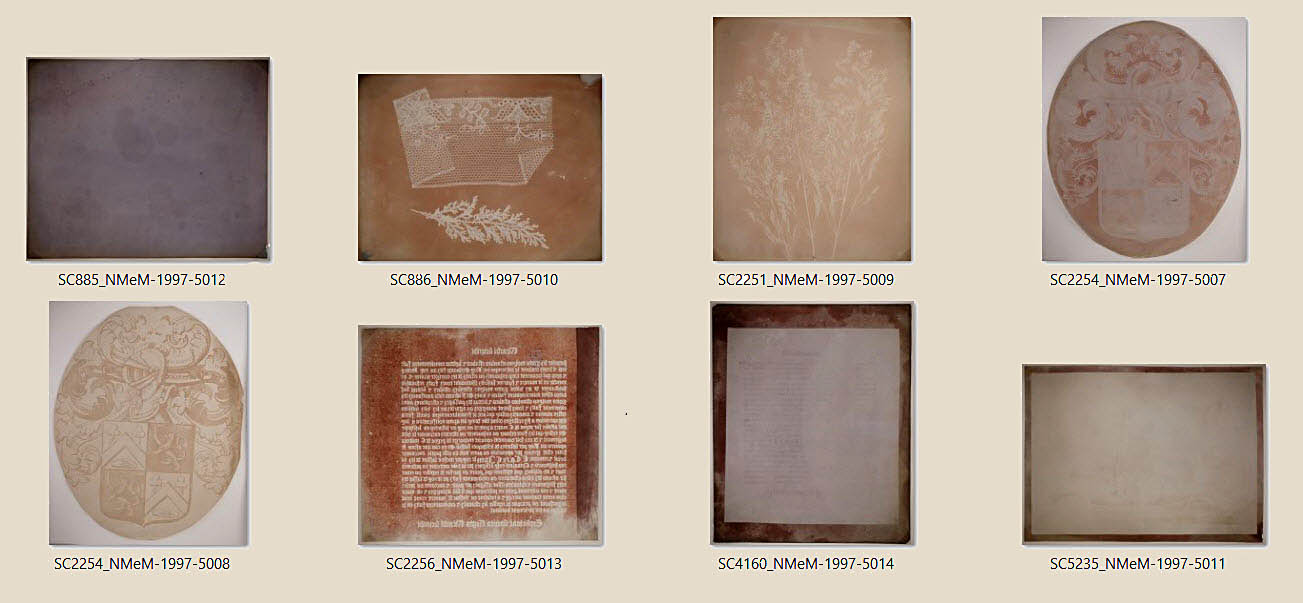

Miraculously, in 1995 eight items from the Trevelyans’ Talbot collection were discovered, some drastically faded, some pretty good. Through a special public appeal they were acquired by the National Media Museum in Bradford. Considering that they were displayed in Birmingham and then in Edinburgh and subsequently in Durham, it is a tribute to Talbot’s success that they survive at all.

Folded Lace and Botanical Specimen (digitally enhanced)

Folded Lace and Botanical Specimen (digitally enhanced)

At Birmingham Talbot had displayed a number of categories of photogenic drawings. A large proportion were direct copies of flat objects placed directly on the photographic paper – photograms as we would now style them – visible on this example is a pencil X, designating the sensitive side.

Coat of arms, “from an old painted glass” – negative and print (digitally enhanced)

Antique painted glass not only provided an interesting and transparent subject for photography to replicate, but its colours also demonstrated the spectral response of the photogenic material. The negative for this pair was titled by Talbot and he noted on the verso that it was a five minute exposure, fixed with bromine.

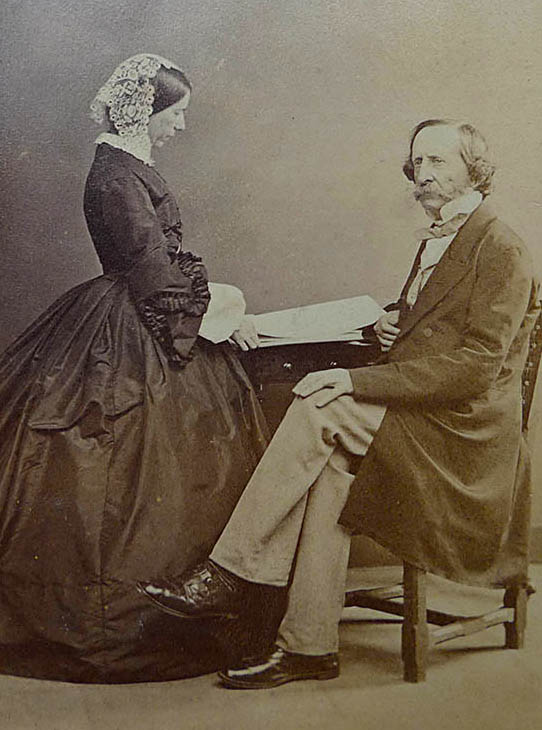

I must admit that I find the stuffy Sir Walter to be a tough read, but the contrast could not be more dramatic with his wife, Lady Pauline, née Jermyn (1816-1866). A vicar’s daughter, she was slight of build with striking hazel eyes, precocious, independent minded and “the despair of her stepmother.” In her youth she avoided other children, instead wandering the Cambridge fens to chat with the gypsies and the sedgecutters. Her proud and supportive father educated her at home, giving her free run of his library, where she was a compulsive reader of Sir Walter Scott. Pauline became a close friend and confidant of John Ruskin. The Pre-Raphaelite artist William Bell Scott, recalled “Pauline, my never-to-be-forgotten good angel; small, quick, with restless bright eye that nothing in heaven or earth or under the earth escaped; appreciative, yet trenchant; satirical, yet kindly; able to do whatever she took in hand, whether it was to please her father in Latin or Greek, or herself in painting and music; intensely amusing and interesting to the men she liked, understanding exactly how much she could trust them in conversation on dangerous subjects, or in how far she could show them she understood or estimated them. This was intensified by the want of humour and imagination in Sir Walter, which must have been a grievance, but was only perceptible as a secret amusement to her.” Although primarily interested in science, Pauline was an accomplished artist and an etcher of her own works.

Her diaries, mostly at the University of Kansas with some in the Newcastle University Library, are fascinating (water damaged and written in an enthusiastic hand, they are also quite a challenge). Mentions of photography are buried within them, from when she saw her first photogenic drawing in May 1839 through to when she started taking calotypes herself. Her birthday happened to be on 25 January, and in 1845, by chance the sixth anniversary of Talbot’s first exhibition at the Royal Institution, Sir Walter presented her with her own calotype camera.

Pauline Trevelyan, ‘Part of Quadrangle Leicesters Hospital Warwick’, March 1845, salt print from a calotype negative.

Pauline Trevelyan, ‘Part of Quadrangle Leicesters Hospital Warwick’, March 1845, salt print from a calotype negative.

Alexander Munro, Lady Trevelyan, 1855 in the central hall of Wallington.

Virtually none of her photographs are known to have survived; the above example was tipped into one of her diaries. She became gravely ill and in April 1866 John Ruskin joined her and Sir Walter on a Continental tour, hoping for recuperation. In Neuchâtel on 13 May, she went into spasms with Sir Walter holding her hands and Ruskin steadying her feet. Years later Ruskin returned to make a drawing of her gravesite there. More about her reactions to photography can be found in the pdf in the notes below.

Edinburgh later would be the residence of the Talbot family for extended periods, most importantly when Henry Talbot conducted many of his photoglyphic experiments there. During the Christmas period in 1839 it was the scene of perhaps his most widely-visited exhibit. Somewhere there should be diaries or notes by people who attended Dr Reid’s exhibition and within these just might be recorded early reactions to the new art. I hope that our readers can trace these. Do let me know.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Unknown photographer, Pauline and Sir Walter Trevelyan, albumen cdv, ca. 1863, Wallington, Northumberland, National Trust. • Letter, WHFT to Sir Walter Trevelyan, 5 July 1839, Talbot Correspondence Project Document no. 03901. • Letter, Trevelyan to WHFT, 25 July 1839, Talbot Correspondence Doc. no. 03910. • Sometimes Talbot listed what he sent his colleagues, but unfortunately here recorded only the total number in his notebook Memoranda June 1838, the British Library, London. • Sir WC Trevelyan, diary entry for 12 September 1839; WCT260, Newcastle University Library. • Pauline Trevelyan, diary entry for 26 December 1839; MSC133 v.12, Spencer Research Library, the University of Kansas. • Sir WC Trevelayan, diary entry for 25 December 1839; WCT260, Newcastle University Library. • It is unknown at present the exact dates of issue of the first edition and second one (and they were called editions, not printings). The first shown here is in the Sackler Library of the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford; the second is in the National Art Library in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. • WHFT, Folded Lace and Botanical Specimen, photogenic drawing negative, 1839, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1997-5010, Schaaf 886. • WHFT, Coat of arms, taken ‘from old painted glass’, photogenic drawing negative and salted paper print, 1839, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1997-5007 and 1997-5008, Schaaf 2254. • For more on the Edinburgh exhibition, see my “Henry Talbot’s First Exhibition in Scotland,” Studies in Photography, 1998, pp. 25-28 – you can download a pdf of this here. • Quoted from John Batchelor, Lady Trevelyan and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (London: Chatto & Windus, 2006), p. 2. • Autobiographical Notes of the Life of William Bell Scott, ed. William Minto (New York: Harper & Bros. 1892), p. 256. • Pauline Trevelyan, Part of Quadrangle Leicesters Hospital Warwick’, March 1845, salt print from a calotype negative, Newcastle University Library. • See my ” ‘Splendid Calotypes’ and ‘Hideous Men’: Photography in the Diaries of Lady Pauline Trevelyan,” History of Photography, v. 34 no. 4, November 2010, pp. 326-341 – you can download a pdf of this here.