We have already explored Henry Talbot’s first public exhibition of his photographs, displayed for one day on 25 January 1839 at the Royal Institution in London. It was a hastily prepared show in response to the surprise announcement by Daguerre. In the dark January weather and under pressure of time, Talbot had no choice but to pull together those examples he still had from earlier years. As 1839 progressed, in spite of miserable weather Talbot was able to expand on this portfolio. He was preparing for his second and what would be his largest exhibition. The forum was the annual meeting of The British Association for the Advancement of Science, which brought together up to 1500 amateur scientists from throughout the country. It was time to properly present his new art.

The annual meeting was an important one and gave the host city not only a tremendous influx of visitors but also the chance to showcase their strengths. There was tremendous incentive to create exhibitions and other supplementary events. Birmingham was the host for 1839 and one of its major events was an ‘Exhibition of the Illustrations of Manufactures, Inventions and Models, Philosophical Apparatus’. Popularly called The Model Room, it was held in the New Department, a large room at the front of King Edwards School on New Street. Designed by Charles Barry, originally planned as a library but instead used as a teaching area, the room accommodated over 200 exhibits including Talbot’s Photogenic Drawings. It was an enormously ambitious undertaking. However, not all was well, for in the summer leading up to the event there were Chartist uprisings in the area. In July, Talbot wrote to Sir John Herschel that “I am afraid our Birmingham meeting will be greatly discouraged by these events, if indeed it takes place at all. A Chartist irruption … would put fly to all the sciences.” We don’t know precisely how many delegates braved the political unrest, but the turnout was better than expected.

Talbot made arrangements for glass cases to show the examples of his work. His mention in the published Catalogue was short and minimally informative. Once the initial shock was over, Henry had the time to consider the relative advantages of his photogenic drawing and the daguerreotype. Reports coming back from Paris gave him a good idea of the strengths and limitations of Daguerre’s use of silvered copper plates. Consequently, Talbot put together a substantial exhibit – 93 items in all – designed to demonstrate the versatility of his work on paper.

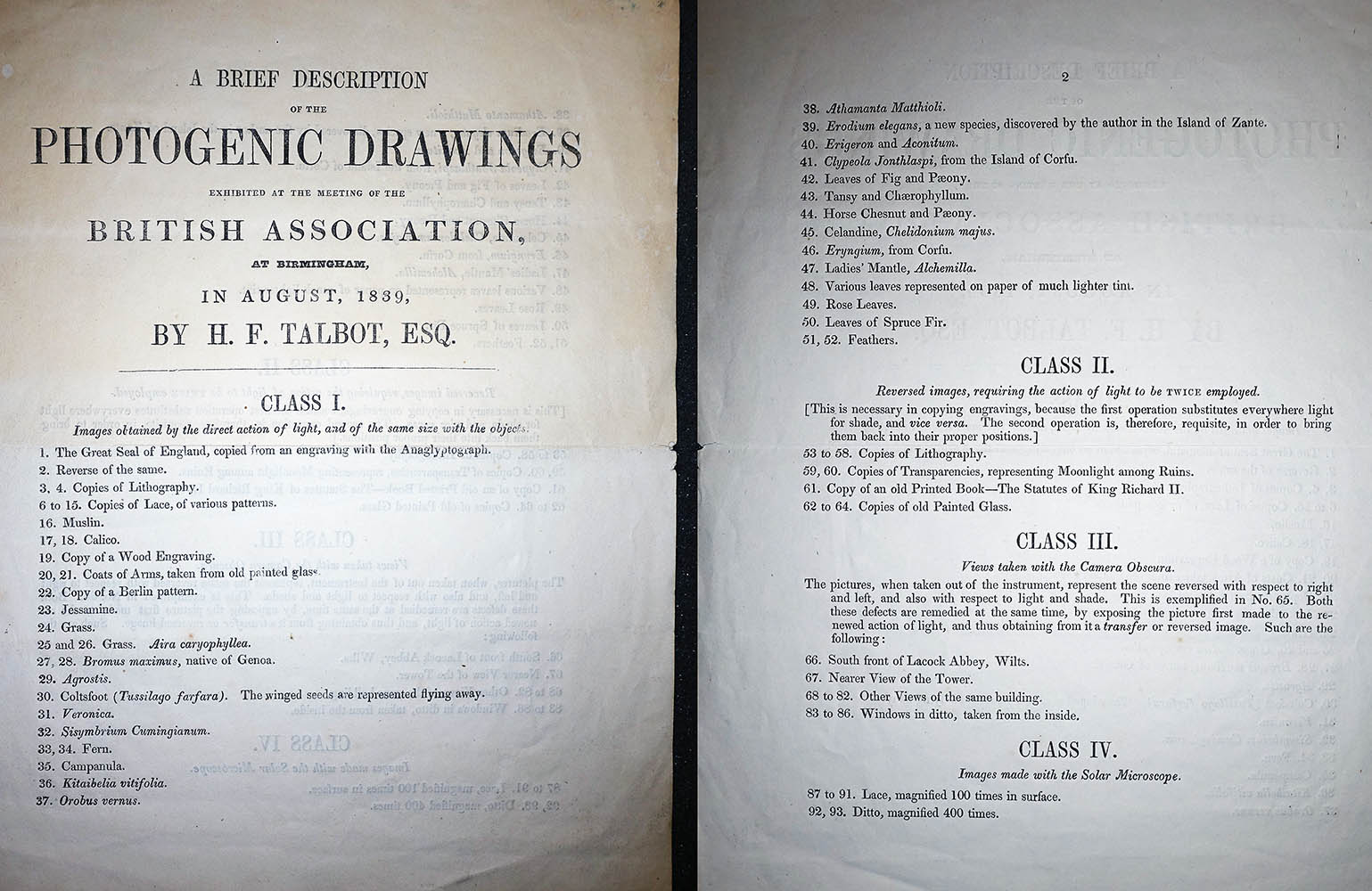

Fortunately he printed up a fairly detailed listing of what he exhibited, splitting his exhibits into four major classes. This illustrates his checklist – you can read the fully transcribed text here.

Although I cannot be absolutely certain of the specific prints and negatives that he showed I have selected examples below that all pre-date this August 1839 exhibition.

WHFT, The Great Seal of England [digitally enhanced version on the right]

WHFT, The Great Seal of England [digitally enhanced version on the right]

Class I. was for ‘Images obtained by the direct action of light, and of the same size with the objects.’ Today we would call these photogram negatives. At fifty-two examples, this was well over half the show. Part of the reason might have been that these were the easiest for Talbot to produce, especially with uncooperative light. But equally he never lost his admiration for these direct self-tracings of Nature’s hand. Many of the exhibits were representations of botanical specimens, along with copies of lace and muslin and importantly copies of lithographs and other examples of graphic art.  John Bate’s machine traced a needle over a three dimensional item such as a medallion. Through a complex mechanism, the contours were translated into curves and another needle cut into a printing plate. The result was a three-dimensional appearing intaglio engraving. Talbot then translated that into the photographic medium.

John Bate’s machine traced a needle over a three dimensional item such as a medallion. Through a complex mechanism, the contours were translated into curves and another needle cut into a printing plate. The result was a three-dimensional appearing intaglio engraving. Talbot then translated that into the photographic medium.

Realising that negatives were challenging visuals for most people to read, his Class II. was ‘Reversed images, requiring the action of light to be twice employed.’ In other words, prints from negatives. This not only returned the tones to their normal structure but also corrected the lateral reversal of the negative. We have already seen how the blue sensitivity of these early photographic materials distorted the colour arrangements, in this case of a transparent view on paper.

Talbot’s Class III was the one that he should have anticipated to be the most popular, ‘Views taken with the Camera Obscura.’ Apparently he showed only one negative here, item no. 65, but didn’t reveal the subject. A negative of his home of Lacock Abbey was the most likely.

Carrying on with Class III, Talbot showed numerous prints made from his in-camera photogenic drawing negatives. Four of them were of windows in Lacock Abbey, “taken from the inside.”

His final Class IV was for ‘Images made with the Solar Microscope.’ These were undoubtedly designed to appeal to the scientific audience. Above is a piece of lace magnified 400 times, sent by Talbot to his botanical friend Antonio Bertoloni at about the same time as when he was preparing for Birmingham.

On 19 August 1839, more than half a year after Talbot had freely disclosed the working details of photogenic drawing, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre finally secured his pension and disclosed his. Perhaps intimidated by the members assembled in the impressive chamber for the joint meeting of the Académie des Science and the Académie des beaux-arts, Daguerre’s voice failed him and François Arago had to make the presentation. Barely a week later, on 26 August, Talbot was called on to explain what he knew of Daguerre’s process. The details “reaching us during the meeting of the British Association, gave rise to an animated discussion … and I took the opportunity to lay before the Section the facts which I had myself ascertained in metallic photography.” His observations were based on “the hasty consideration which he had been able as yet to give.” Unfortunately, Talbot’s ‘Remarks on M. Daguerre’s Photogenic Process’ do not seem to have been preserved as a paper and given the circumstances he may have spoken off the cuff. However his observations were summarized by an unidentified attendee and published in the BAAS’s Report. Realising that Daguerre’s process was based on the light sensitivity of silver iodide, Talbot referred to his own earlier researches on the optical and chemical properties of that substance. He had considered using silver iodide but had found it “much inferior” to silver chloride in sensitivity. “Now, however, M. Daguerre has disclosed the remarkable fact, that this feeble impression can be increased, brought out, and strengthened, at a subsequent time, by exposing the plate to the vapour of mercury.” Talbot questioned Daguerre’s instructions on mercury fuming, “for who ever heard of masses of vapour possessing determinate sides, so as to be capable of being presented to an object at a given angle?” Daguerre had raised the possibility of colour reproduction, something both Talbot and Sir John Herschel had also noted in their work. But Talbot’s greatest puzzle was the fact “that it had been repeatedly stated in the Comptes rendus of the French Institute, that M. Daguerre’s substance was greatly superior in sensitiveness to the English photogenic paper. It now, however, appeared that this was to be understood in a peculiar sense, inasmuch as the first or direct effect of the French method was very little apparent, and was increased by a subsequent process.” It is unclear just how much Daguerre himself comprehended about the development of the latent image, but he readily understood its practical implications. Did Daguerre understand the special significance of the latent image or did he merely see this as one step in the totality of his process? Talbot struggled with the idea that the Daguerreotype and photogenic drawing had a similar initial sensitivity to light, but that Daguerre’s method then depended on an additional process. What did he understand of the latent image at the time? Little more than a year later, of course, this advantage would become clear to Talbot with the discovery of his developed calotype negative process. Henry concluded his summary with the statement, “these facts (he thought) serve to illustrate the fertility of the subject, and show the great extent of yet unoccupied ground in this new branch of science.” A transcription of the full text of Talbot’s observations can be read here.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT to Herschel, 19 July 1839, Talbot Correspondence Project Document no. 03908. • Advertisement, Birmingham Journal, 7 September 1839. • Catalogue of the Illustrations of Manufactures, Inventions and Models, Philosophical Instruments, etc., Contained in the Second Exhibition of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, held at Birmingham, August, 1839 (Birmingham: Wrightson and Webb, 1839); the British Library, London. • WHFT, A Brief Description of the Photogenic Drawings Exhibited at the Meeting of the British Association, at Birmingham, in August 1839; The George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY. • WHFT, The Great Seal of England, copied from an engraving with the Anaglyptograph, photogenic drawing negative, 1839; Fox Talbot Archive, the Bodleian Libraries, FT10021; Schaaf 3799. • The Great Seal of England, Engraved with Bate’s Patent Anaglyptograph, engraving, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid. • Reeve & Sons, Tintern Abbey, Transparent View, pigment on paper, Fox Talbot Archive, the Bodleian Libraries, FT11993; WHFT, Copy of a Transparency, representing Moonlight among Ruins, salt print from a photogenic drawing negative, 1839, Private Collection, Schaaf 1645. • WHFT, South front of Lacock Abbey with Sharington’s Tower, photogenic drawing negative, 16 August 1839. Royal Photographic Society Collection, the National Media Museum, Bradford, RPS025120, Schaaf 2307. • WHFT, Middle Window South Gallery, salt print from a photogenic drawing negative, April 1839. Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, LA2967; Schaaf 3694. • WHFT, Lace magnified 400 times in the solar microscrope, photogenic drawing negative, 1839. Bertoloni Album, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 36.37(14), Schaaf 2281. • WHFT, in a letter of 21 December 1842, published “On the coloured Rings produced by Iodine on Silver, with Remarks on the History of Photography,” Philosophical Magazine, 3rd series, no. 143, February 1843, p. 97.