Earlier this week, on 25 January, Burn’s Night was celebrated worldwide and I trust that everyone sought out their favourite haggis. In all of Talbot’s writings there is no evidence that he ever got a chance to enjoy this Scottish delicacy (but none to the contrary either). The 25th of January has a special significance not only for the Scots and gourmands, but also for photohistorians. It was the date of Talbot’s first public exhibition of photography. Some may come to feel that the haggis is the last pretty picture in this post, but for the below I must agree with the photographer and early historian, Vernon Heath, who upon seeing Talbot’s primitive works at this first exhibition “was from that moment in heart and spirit a disciple of the new science – Photography.”

The new art of photography was born into a world of inescapable tension. In January 1839, sketchy accounts reached Britain that the Parisian artist and showman, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, had devised a seemingly magical means of capturing the images in a camera obscura. François Arago communicated this to the Académie des Sciences on 7 January and Talbot seems to have first learned of it from the January 12th Literary Gazette. Nothing about Daguerre’s process was disclosed save for the hint that the images had been preserved on plates of copper: “Views of trees, the Boulevards of Paris, a dead spider seen in the solar microscope – in short, anything motionless could be depicted with the utmost fidelity.” Talbot had no way of evaluating Daguerre’s achievement, but it sounded exactly like what he had conceived of in 1833 and realised by 1834. He hurried to put on record his own approach to image making, not in competition with Daguerre, but rather to establish his independent priority solely for what he had done.

Talbot felt that he had been “placed in a very unusual dilemma (scarcely to be paralleled in the annals of science): for I was threatened with the loss of all my labour, in case M. Daguerre’s process proved to be identical with mine, and in case he published it at Paris before I had time to do so in London.” His mother, Lady Elisabeth, was typically scathing: “I shall be very glad if M. Daguerre’s invention is proved to be very different from yours. But as you have known it five years à quoi bon concealing it till you could by possibility have a competitor? If you would only have made it known one year ago, it could never have been disputed, or doubted.”

January 25th provided Talbot with his earliest opportunity to approach the scientific public. He turned to his friend Michael Faraday, who addressed the more than 300 people who had assembled at the Royal Institution for the popular Friday evening lecture. After the lecture, Faraday announced the parallel discoveries of Daguerre and Talbot. It was customary for him to mount a temporary exhibition in the library, and that evening he invited the audience to inspect diverse curious objects such as papier maché ornaments, specimens of `artificial fuel,’ and a collection of 16th c. engravings. He was also able to show examples of Henry Talbot’s black magic. Surprised by the new invention himself, Faraday could only observe that “no human hand has hitherto traced such lines as these drawings display; and what man may hereafter do, now that Dame Nature has become his drawing mistress, it is impossible to predict.” We don’t have any precise record of what Talbot exhibited that night – they had to be photographs leftover from his experiments from 1834-1836. One possibility is a mounted piece of lace that we have seen in an earlier post. Another is the well-known presentation above, clearly meant for an audience and clearly early.

Talbot wanted to establish the wide-ranging possibilities of his invention and he recorded that he showed images of “flowers and leaves; a pattern of lace; figures taken from painted glass; a view of Venice copied from an engraving; some images formed by the Solar Microscope, viz. a slice of wood very highly magnified, exhibiting the pores of two kinds, one set much smaller than the other, and more numerous. Another Microscopic sketch, exhibiting the reticulations on the wing of an insect. Finally: various pictures, representing the architecture of my house in the country; all these made with the Camera Obscura in the summer of 1835.”

We cannot know precisely what images Talbot exhibited, nor if they survive, but below is a mini-gallery of such artefacts that I am personally confident date to this pre-1839 period and are typical of what he described. Bear in mind that these are all approaching two centuries in age and were certain to be stronger and more harmonious in tone when they were first seen in 1839. Also, in an era when we are not at all surprised with the daily drumbeat of new inventions and improved technology, of OLED television and incredibly detailed digital representations, we have to adjust our eye to the more innocent and uncluttered mindset of a 19th century person.

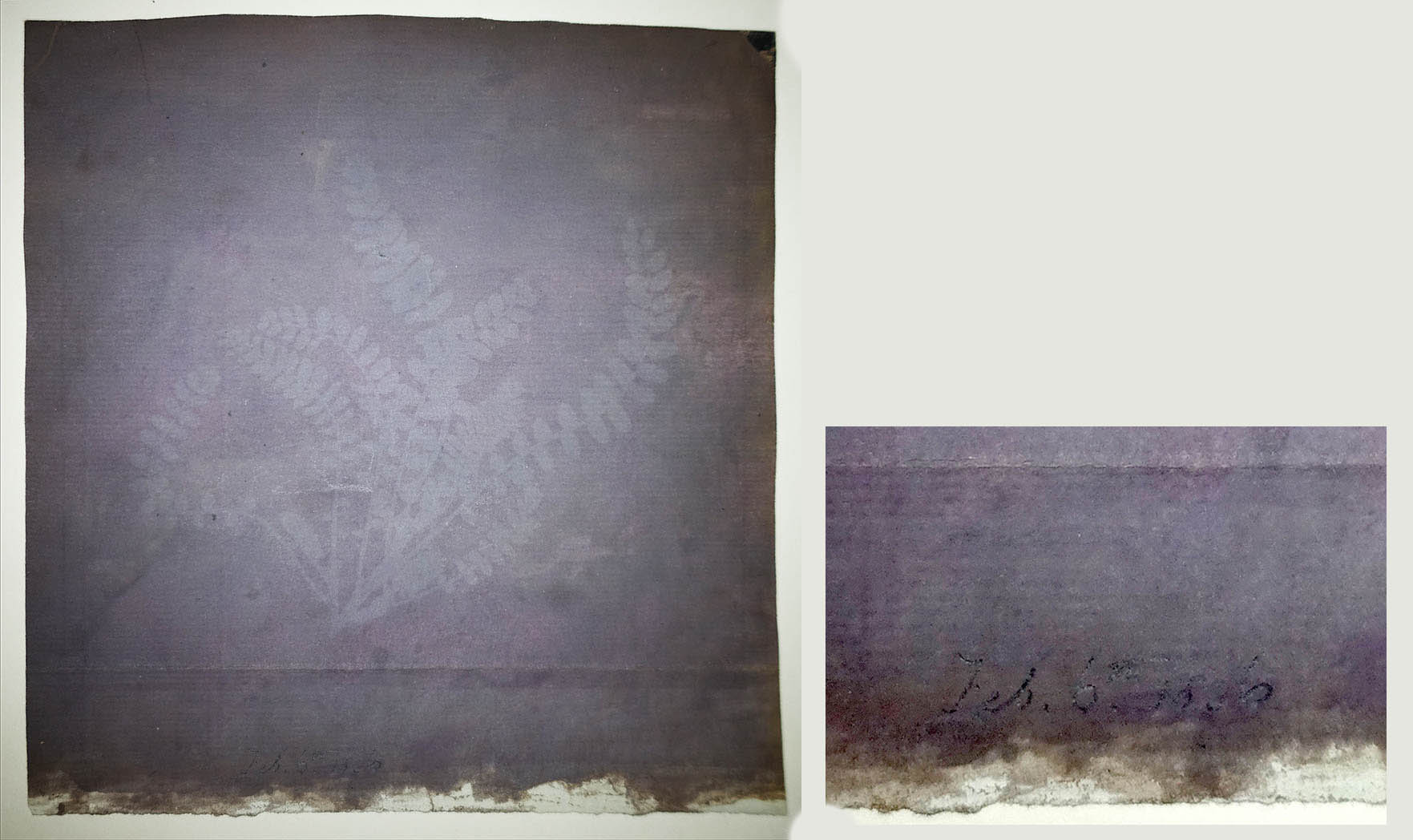

Like the previous example, Talbot made the dating of this easy – he inscribed the date in pencil, 6 February 1836, and this image must at least be similar to the ‘flowers and leaves’ that he showed. Although it is not apparent in these reproductions, the paper was made by J Coles and is a laid paper – Talbot would soon avoid the grid structure that this imposed on his images.

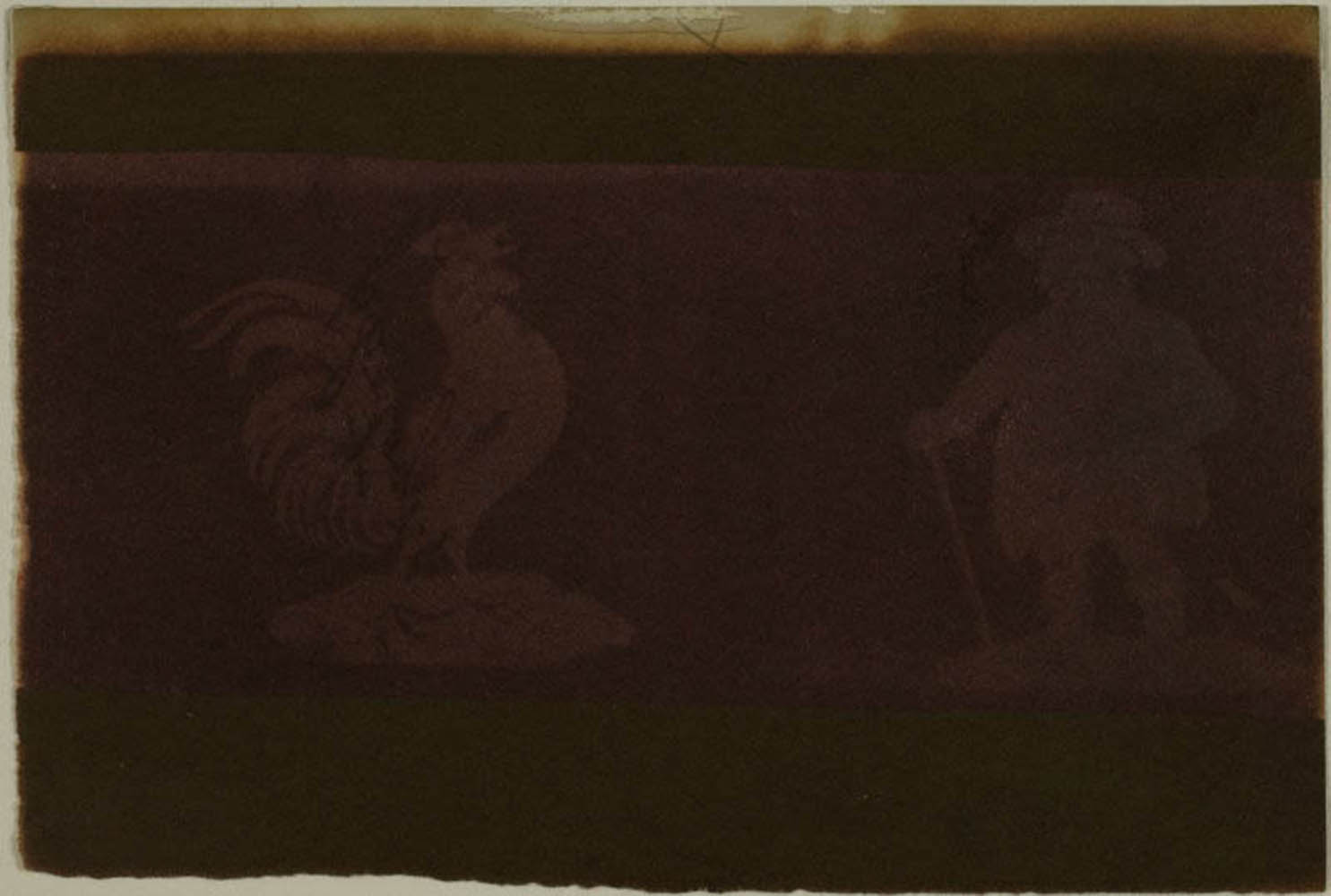

The ‘coloured glass’ might have been from a window, such as the example for an earlier post, but more likely at this stage was from a more convenient object such as this glass lantern slide. Note the pencil X at the top, designating the sensitised side of the paper. Since there was no emulsion – just silver compounds trapped within the fibrous structure of the paper – once dried it was very difficult to tell which side was coated.

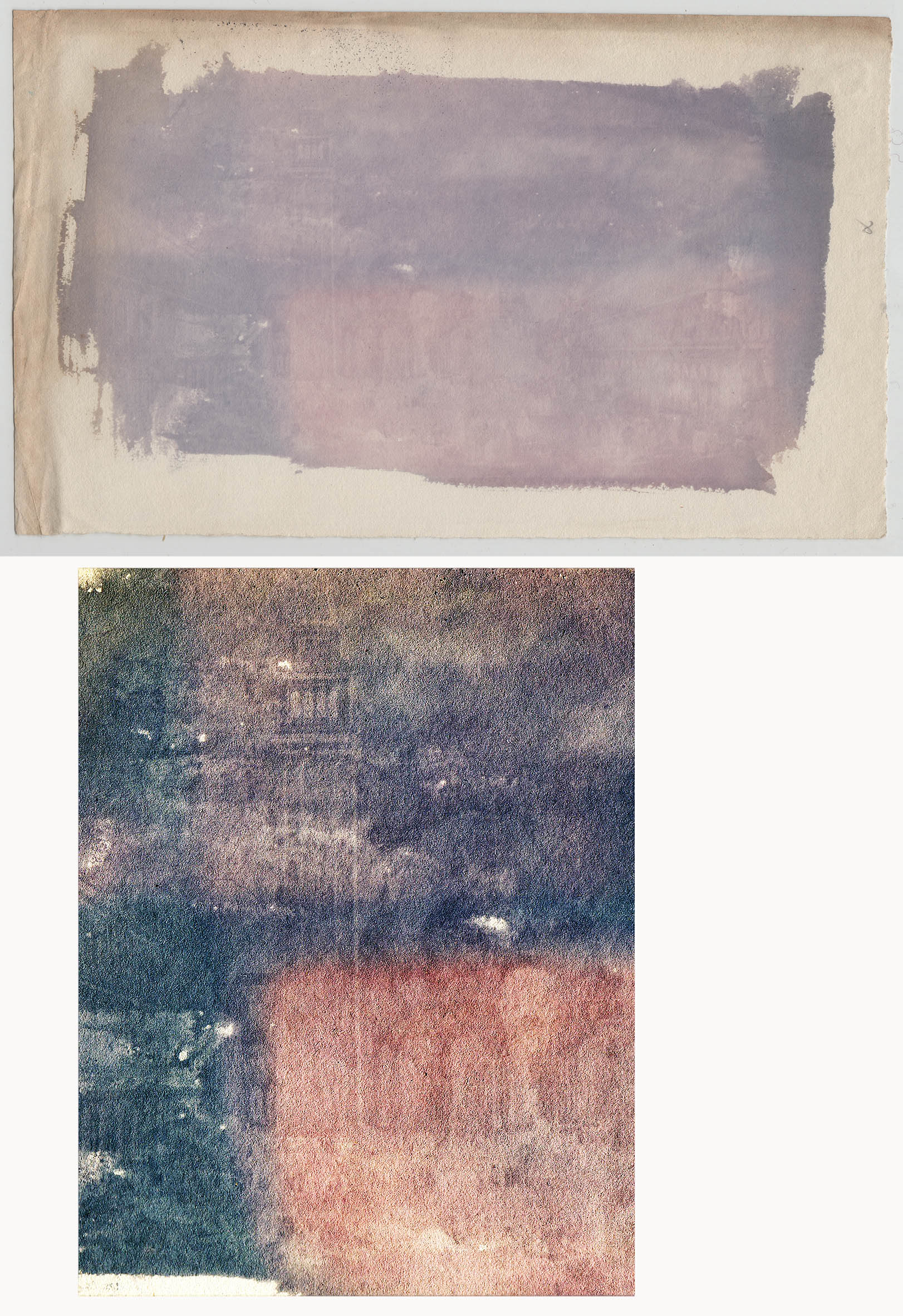

The ‘view of Venice’ was almost certainly this one of St Marks Square, showing the original tower that none of us has ever seen – I’ve enhanced a detail here to make the image more identifiable. This is on an unusually thin paper, another indication that it was made in the early period before he settled on Whatmans and other papers with more substance.

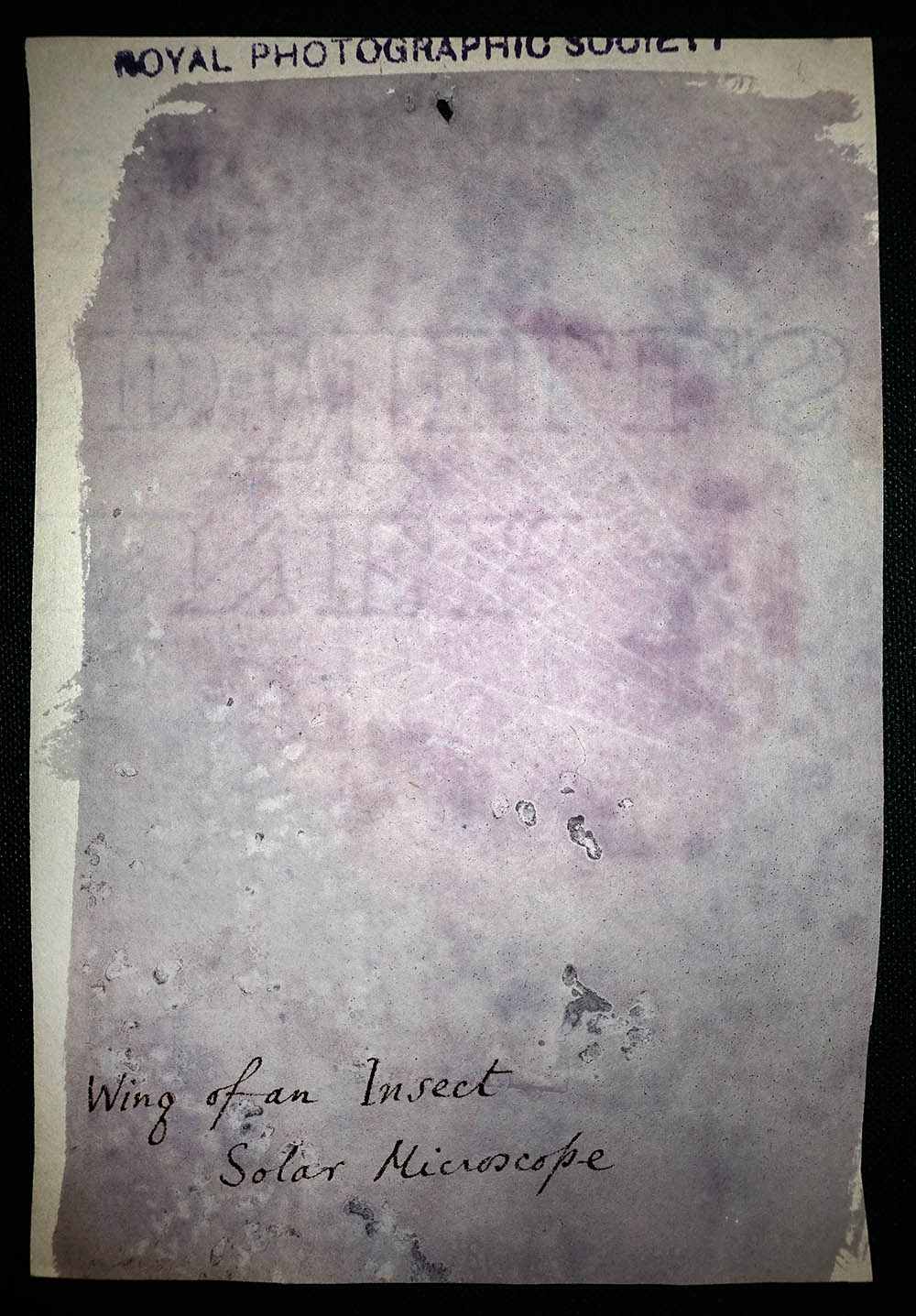

The ‘Wing of an insect’ is now slightly less clear than an early collection stamp (no living soul nor friend of ours was responsible for this) but you can still make out a fan structure. The titling is in Talbot’s hand. The partial watermark is that of Turner Chafford Mills 1834. While watermarks were unavoidable in good paper, Talbot would soon learn to cut his sheets so that the blank portions were reserved for negatives and the watermarked portions for prints.

Although Faraday’s lecture and the exhibition were noted in the weekly journals, audience reaction is difficult to judge (at least until some kind reader of these missives turns up the previously-unknown notebook or letter of someone who attended and had a reaction similar to Vernon Heath’s). The Literary Gazette briefly described a few of the pictures: “His copying of engravings (there is a sweet one of Venice), by first getting them with the lights and shades reversed, but then copying from the reversed impression, as before, is singularly ingenious. Figures painted on glass are exquisitely rendered; and an oriel window of many feet square is reduced to a picture of two inches, in which every line is preserved with a minuteness inconceivable until seen by the microscope.” A less sympathetic reaction came from the pen of the respected but aging surgeon, Sir Anthony Carlisle (who was to proclaim his own – undocumented – invention of photography): “At an evening meeting holden at the Royal Institution on Friday last, several specimens of shaded impressions were exhibited, produced by the new French Camera. The outlines, as well as the interior forms of the objects, were faintly pictured, and hence the application of this method of impressing accurate designs may become disregarded after public curiosity subsides.”

Henry Talbot, however, felt that he had finally shared with an audience “a little bit of magic realised: – of natural magic.” Just six days after this exhibition, on 31 January, his first paper on photography was read before the assembled members of They Royal Society of London. It seems to me that seven days from now we should consider Talbot’s first reflections on his new art.

Larry J Schaaf

Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Tessa Watson, Edinburgh, Split Haggis. • Vernon Heath, “On the Autotype and other Photographic Processes and Discoveries,” Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain, v. 7 no. 61, 20 February 1874, p. 220. • The Literary Gazette, no. 1147, 12 January 1839, p. 28. • WHFT, letter of 8 April 1839 to the editor of The Literary Gazette, no. 1160, 13 April 1839, pp. 235-236; Talbot Correspondence Document no 03857. • Lady Elisabeth Feilding to WHFT, 3 February 1839, Doc. no. 03787. • WHFT, Latticed Window (with the Camera Obscura), photogenic drawing negative, August 1835, Talbot Collection, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-361, Schaaf 2242. • Faraday’s comment was recalled in Vernon Heath’s Recollections (London: Cassell & Company, 1892), p. 49. • WHFT, “Photogenic Drawing,” letter to the editor dated 30 January 1839, The Literary Gazette, no. 1150, 2 February 1839, pp. 72-74; Doc no. 03782. • WHFT, Botanical Specimen, photogenic drawing negative, 6 February 1836, Talbot Collection, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-361, Schaaf 2243. • WHFT, Copy of a Coloured Lantern Slide, photogenic drawing negative, probably 1835, Art Institute of Chicago, Schaaf 3671. • WHFT, Copy of an engraving of St Marks Square, Venice, photogenic drawing negative, probably 1835; Photographic History Collection, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1995.206.169; Schaaf 425. • WHFT, Wing of an Insect, in the Solar Microscope, photogenic drawing negative, probably 1835, Royal Photographic Society Collection, National Media Museum, Bradford, 025083, Schaaf 2134. • “The New Art,” The Literary Gazette, no. 1150, 2 February 1839, p. 73. • Letter from Anthony Carlisle, dated 30 January 1839, “On the Production of Representations of Objects by the Action of Light,” Mechanics Magazine, v. 30 no. 809, 9 February 1839, p. 329. • WHFT, “Photogenic Drawing,” letter to the editor dated 30 January 1839, The Literary Gazette, no. 1150, 2 February 1839, p. 74; Doc. no. 03782.