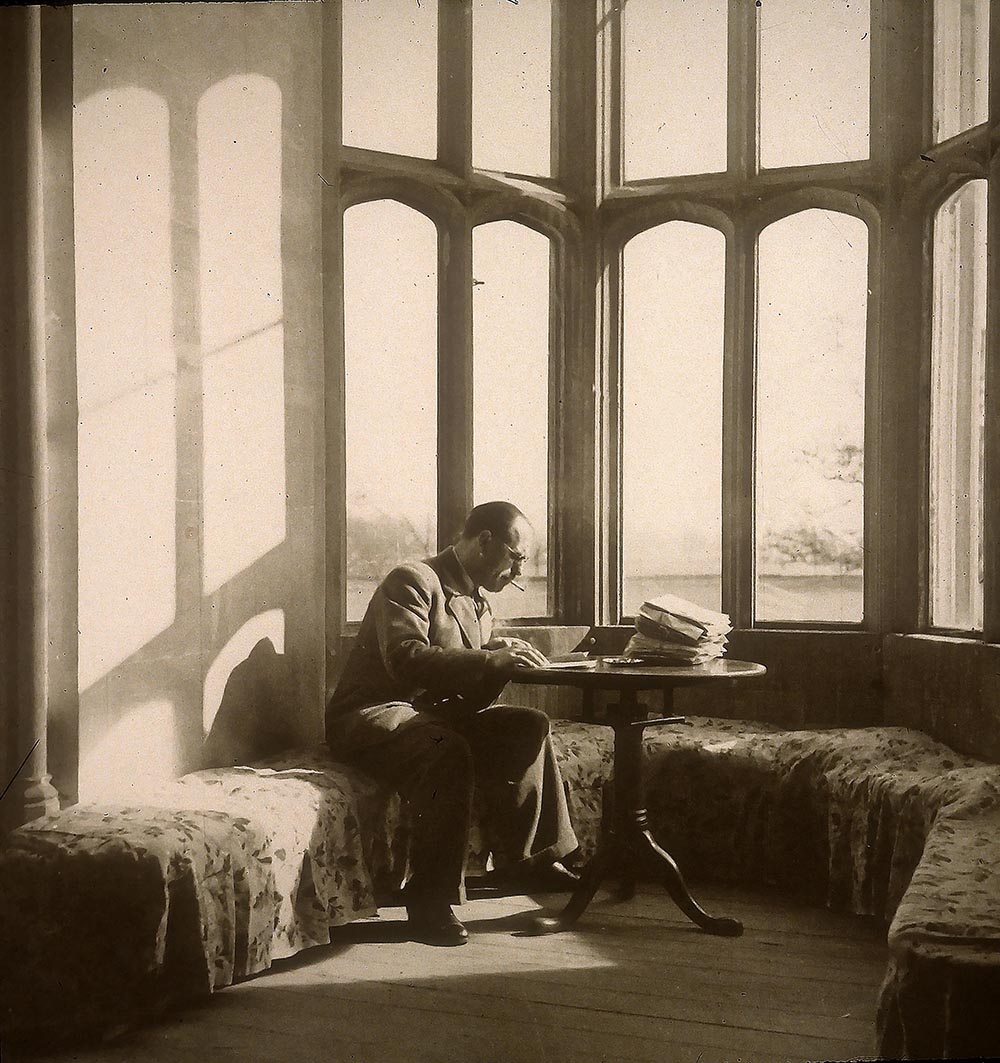

Harold White (1902-1983) was the foremost Talbot scholar of his generation and in many ways shaped subsequent research in this field. A highly accomplished professional photographer, his 1949 endorsement of the ‘Nebro’ tripod would have carried more than sixteen stones of weight with his colleagues and must have contributed to its sales. He was a man of good cheer, rarely observed without a smoke in his hand. Harold undoubtedly staged this ebullient self-portrait in the garden behind his house (subsequently airbrushed out by the BJP). He probably used one of his larger plate cameras since his later favourite Rolleiflex would not have benefitted as much from a tripod.

It was in his capacity as a photographer that White first visited the village of Lacock in 1944, on assignment in a propaganda effort to depict an English village doing just fine, thank you, during the war. Matilda Talbot, the inventor’s granddaughter, was making her own contributions to the war effort, additionally taking the precaution of hiding the Lacock copy of the Magna Carta under the flagstones in Sherington’s Tower, just in case the threatened invasion came to pass. White was obviously captivated by Miss Talbot and the stories of her grandfather (as am I, and we’ll be returning to look at her in more depth in a future blog). After the war White began to visit Lacock Abbey regularly, often bringing his wife and daughter along for extended stays. It was during one of these visits that they unearthed Talbot’s plaster cast of Patroclus, long abandoned in a shed and caked with mud. White’s wife Edith and his young daughter Patricia spent some time cleaning him up using toothbrushes. His somewhat softened features today may have resulted from this. Miss Talbot had been seeking someone to write a biography of Henry Talbot and in 1946 Beaumont Newhall approved of her choice of Harold White. By 1950 she and White had agreed to co-author the text. It was a book that was never to be completed but the process of preparing for it was to have enormous influence on the organization and preservation of the Lacock Abbey collection. This has affected Talbot studies ever since.

Part of what sets Harold White apart from more casual researchers (then and now) was his dedication to anchoring his conclusions by reference to the abundant original documents. In a self portrait from around 1950, he has staged himself in the South Gallery of Lacock Abbey, in the bay just west of the famous Oriel Window. Little did he know that the sight of the copious sunlight, the teetering stack of original letters and the dangling ash of his cigarette would prove uncomfortable for later conservators. It is a cinematic view, its lighting mimicking films of the period. The stack of letters symbolizes hard work and the cigarette serious intent on the part of the researcher. A very intelligent, creative and hard-working individual, White had no formal training in research or writing. He adopted an empirical approach, trusting that by absorbing the massive amount of information contained in the documents he would learn the truth about Talbot. Sir John Herschel would have approved of this inductive reasoning.

Part of what sets Harold White apart from more casual researchers (then and now) was his dedication to anchoring his conclusions by reference to the abundant original documents. In a self portrait from around 1950, he has staged himself in the South Gallery of Lacock Abbey, in the bay just west of the famous Oriel Window. Little did he know that the sight of the copious sunlight, the teetering stack of original letters and the dangling ash of his cigarette would prove uncomfortable for later conservators. It is a cinematic view, its lighting mimicking films of the period. The stack of letters symbolizes hard work and the cigarette serious intent on the part of the researcher. A very intelligent, creative and hard-working individual, White had no formal training in research or writing. He adopted an empirical approach, trusting that by absorbing the massive amount of information contained in the documents he would learn the truth about Talbot. Sir John Herschel would have approved of this inductive reasoning.

One frequently overlooked influence that White had on subsequent scholarship stems from this sorting of letters and documents. Facing tens of thousands of sheets of paper, he began to develop a story line and started winnowing out the original documents that to him appeared duplicative or not essential to his story. Which pile a particular document wound up derived less from a qualitative evaluation so much as from a practical one. I’ve touched on this story in an earlier blog: The Big Dig at Lacock Abbey. When Eugene Ostroff came from the Smithsonian in the 196os to catalogue the collection, he applied ‘LA’ numbers to the chronological sequence of letters; LA39-14, for example, was the 14th letter from 1839. He examined the letters that Harold White was reserving for use in his biography but was unaware of an equally large number that White had designated as of ‘Doubtful Use’. Matilda Talbot was gone by then and White’s efforts toward writing the biography were floundering. His visits to Lacock become infrequent. Since Ostroff enjoyed full cooperation from her successor, Colonel Burnett-Brown, this group was probably stored in a remote corner of the Abbey’s attic and long forgotten. I believe that Doug Arnold was the first to re-discover these and Anthony Burnett-Brown very generously made them available to me in the late 1970s. They form an essential part of the Correspondence Project.

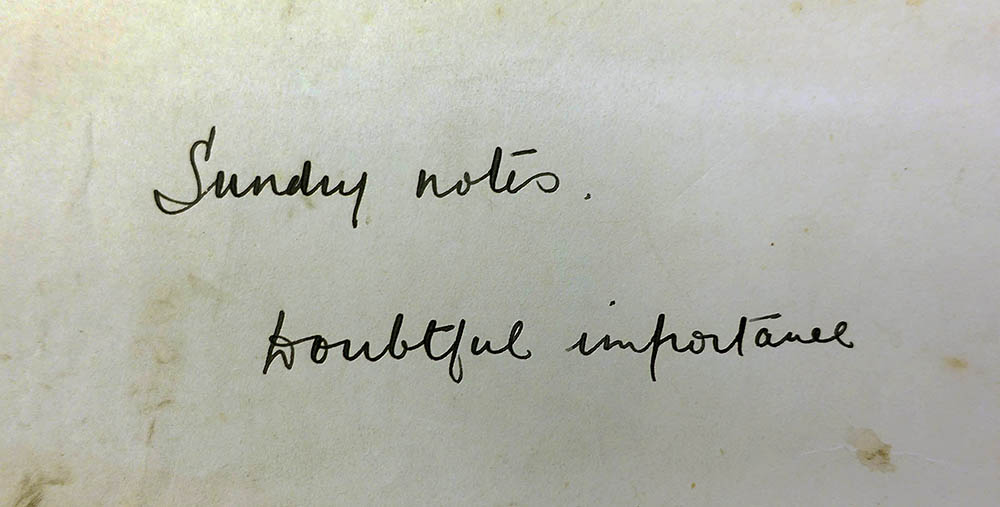

One frequently overlooked influence that White had on subsequent scholarship stems from this sorting of letters and documents. Facing tens of thousands of sheets of paper, he began to develop a story line and started winnowing out the original documents that to him appeared duplicative or not essential to his story. Which pile a particular document wound up derived less from a qualitative evaluation so much as from a practical one. I’ve touched on this story in an earlier blog: The Big Dig at Lacock Abbey. When Eugene Ostroff came from the Smithsonian in the 196os to catalogue the collection, he applied ‘LA’ numbers to the chronological sequence of letters; LA39-14, for example, was the 14th letter from 1839. He examined the letters that Harold White was reserving for use in his biography but was unaware of an equally large number that White had designated as of ‘Doubtful Use’. Matilda Talbot was gone by then and White’s efforts toward writing the biography were floundering. His visits to Lacock become infrequent. Since Ostroff enjoyed full cooperation from her successor, Colonel Burnett-Brown, this group was probably stored in a remote corner of the Abbey’s attic and long forgotten. I believe that Doug Arnold was the first to re-discover these and Anthony Burnett-Brown very generously made them available to me in the late 1970s. They form an essential part of the Correspondence Project. White gathered up the segregated letters and bundled them in paper wrappers. Those bundles that did not make the cut for his planned writing were labeled ‘Doubtful Use’ or simply ‘DU’ and the above example in the British Library is similar to these. I recall them well but sometime in the 1980s the original wrappers seem to have dropped by the wayside. They are not in British Library nor the Fox Talbot Museum. Since the family vacated Lacock Abbey fairly recently and the contents were thoroughly examined, it seems unlikely that any are lurking there. It may be difficult to understand in these days of the ubiquitous auto-focus highly sensitive mobile phone camera, but not too many years ago taking snapshots of ‘trivial’ things was both challenging and expensive. I cannot even find a photograph of one of these ‘DU’ bundles. After rooting through all my own files I asked quite a few colleagues, but so far nobody has turned up such a record photograph. If anybody who researched at Lacock Abbey in the 1980s has a snapshot of one of these wrappers, please get in touch. Surely some visual record of them survives somewhere and the wrappers are/were valuable historical evidence.

White gathered up the segregated letters and bundled them in paper wrappers. Those bundles that did not make the cut for his planned writing were labeled ‘Doubtful Use’ or simply ‘DU’ and the above example in the British Library is similar to these. I recall them well but sometime in the 1980s the original wrappers seem to have dropped by the wayside. They are not in British Library nor the Fox Talbot Museum. Since the family vacated Lacock Abbey fairly recently and the contents were thoroughly examined, it seems unlikely that any are lurking there. It may be difficult to understand in these days of the ubiquitous auto-focus highly sensitive mobile phone camera, but not too many years ago taking snapshots of ‘trivial’ things was both challenging and expensive. I cannot even find a photograph of one of these ‘DU’ bundles. After rooting through all my own files I asked quite a few colleagues, but so far nobody has turned up such a record photograph. If anybody who researched at Lacock Abbey in the 1980s has a snapshot of one of these wrappers, please get in touch. Surely some visual record of them survives somewhere and the wrappers are/were valuable historical evidence. Harold White never finished his biography. Several sets of drafts survive but they all represent various stages of about the first eighty pages of manuscript. This text is a competent and smoothly written survey but lacking in any great insights or analysis. White made detailed lists and extracted many notes. You can tell from his correspondence that he was very perceptive and thoughtful, but this manuscript falls far short of what he really understood. Is it possible that he was too careful, too conservative in putting his thoughts down on paper? In any case, it is clear that in setting the goal of reading all of Talbot’s letters and research notes Harold had set an impossible goal for himself. Especially in the pre-computer days, the process of trying to digest so much material was beyond his reach. There were other frustrations. As part of her efforts to establish the reputation of her grandfather, Matilda Talbot had generously donated more than 6,000 photographs and documents from Lacock Abbey to the Science Museum in 1934. She was shocked when their curator, Alexander Barclay, came to treat this like his personal collection. In turns, Beaumont Newhall, Helmut Gernsheim and Harold White were all denied access to the collection. In 1937, Barclay responded to a request from Newhall that his museum (ie, himself) “reserves to itself the right of research into, and publication of, any original material which it has acquired for its collections. After this has been done the collection will become generally available to students and to the general public.” Today such an attitude is considered to be decidedly unprofessional and a clear violation of ethics and trust, but in the mid-20th century it was not uncommon. Indeed, it was Barclay’s successor, Dr David Thomas who first opened up the collection to the public, encouraging, amongst other things, the major biographies of Talbot by Doug Arnold and Gail Buckland (the latter particularly). It was Dr Thomas’s youthful assistant, John Ward, who finally allowed Harold White into the collection in the 1970s, long after the possibility of White ever completing his biography had passed.

Harold White never finished his biography. Several sets of drafts survive but they all represent various stages of about the first eighty pages of manuscript. This text is a competent and smoothly written survey but lacking in any great insights or analysis. White made detailed lists and extracted many notes. You can tell from his correspondence that he was very perceptive and thoughtful, but this manuscript falls far short of what he really understood. Is it possible that he was too careful, too conservative in putting his thoughts down on paper? In any case, it is clear that in setting the goal of reading all of Talbot’s letters and research notes Harold had set an impossible goal for himself. Especially in the pre-computer days, the process of trying to digest so much material was beyond his reach. There were other frustrations. As part of her efforts to establish the reputation of her grandfather, Matilda Talbot had generously donated more than 6,000 photographs and documents from Lacock Abbey to the Science Museum in 1934. She was shocked when their curator, Alexander Barclay, came to treat this like his personal collection. In turns, Beaumont Newhall, Helmut Gernsheim and Harold White were all denied access to the collection. In 1937, Barclay responded to a request from Newhall that his museum (ie, himself) “reserves to itself the right of research into, and publication of, any original material which it has acquired for its collections. After this has been done the collection will become generally available to students and to the general public.” Today such an attitude is considered to be decidedly unprofessional and a clear violation of ethics and trust, but in the mid-20th century it was not uncommon. Indeed, it was Barclay’s successor, Dr David Thomas who first opened up the collection to the public, encouraging, amongst other things, the major biographies of Talbot by Doug Arnold and Gail Buckland (the latter particularly). It was Dr Thomas’s youthful assistant, John Ward, who finally allowed Harold White into the collection in the 1970s, long after the possibility of White ever completing his biography had passed. The story is necessarily fuzzy, but over time by whatever means White came to possess some incredible photographs. Given their warm relationship, I am sure that he was honest in his dealings with Matilda and that she freely gave him originals. It is possible that he purchased some later from Colonel Burnett-Brown. However, some, like this marvelous 1835 negative of the Oriel Window that he sold to the Rubel Collection, could only have come from the Abbey, not the villagers. Others he may have found distributed elsewhere in Britain, for in the 1950s and 1960s there was almost no market for Talbot originals and they would have been quite affordable.

The story is necessarily fuzzy, but over time by whatever means White came to possess some incredible photographs. Given their warm relationship, I am sure that he was honest in his dealings with Matilda and that she freely gave him originals. It is possible that he purchased some later from Colonel Burnett-Brown. However, some, like this marvelous 1835 negative of the Oriel Window that he sold to the Rubel Collection, could only have come from the Abbey, not the villagers. Others he may have found distributed elsewhere in Britain, for in the 1950s and 1960s there was almost no market for Talbot originals and they would have been quite affordable.This is one of Talbot’s large format negatives taken with his original photogenic drawing method, a print-out process where no development was involved, just solar energy. As miserable as the weather had been in photography’s first public year of 1839, it was brilliant in 1840. Talbot enjoyed fine sunlight starting in the early spring and by summer he was advancing rapidly both technically and aesthetically. The iodide fixing of his negatives made them susceptible to lightening rather than darkening with continued exposure to light, but Talbot and later Harold White knew that the image was still there, just not in a form that our eyes could perceive. White used a modern Metol-Quinone developer to redevelop this negative, recording in a typewritten label that this was based on Talbot’s discovery in September 1840, just as he was inventing the Calotype. In his Notebook Q for 23 September 1840, Talbot found that his ‘exciting liquid’ – his newly discovered gallic acid developer – “restores or revives old pictures on Waterloo paper which have worn out, or become to faint to give any more copies.” As a photographer (lapsed) myself, even over the course of making thousands of prints I never lost the excitement and anticipation of watching the image on a piece of printing paper slowly but steadily gather strength in the pan of developer (go watch the classic film Blow Up if you have never had this experience yourself). One can imagine Harold White’s sense of triumph and satisfaction when he took a blank or nearly so Talbot original and brought it back to life. He must have felt that he had been transplanted into Talbot’s body of more than a century earlier as he watched the image form.

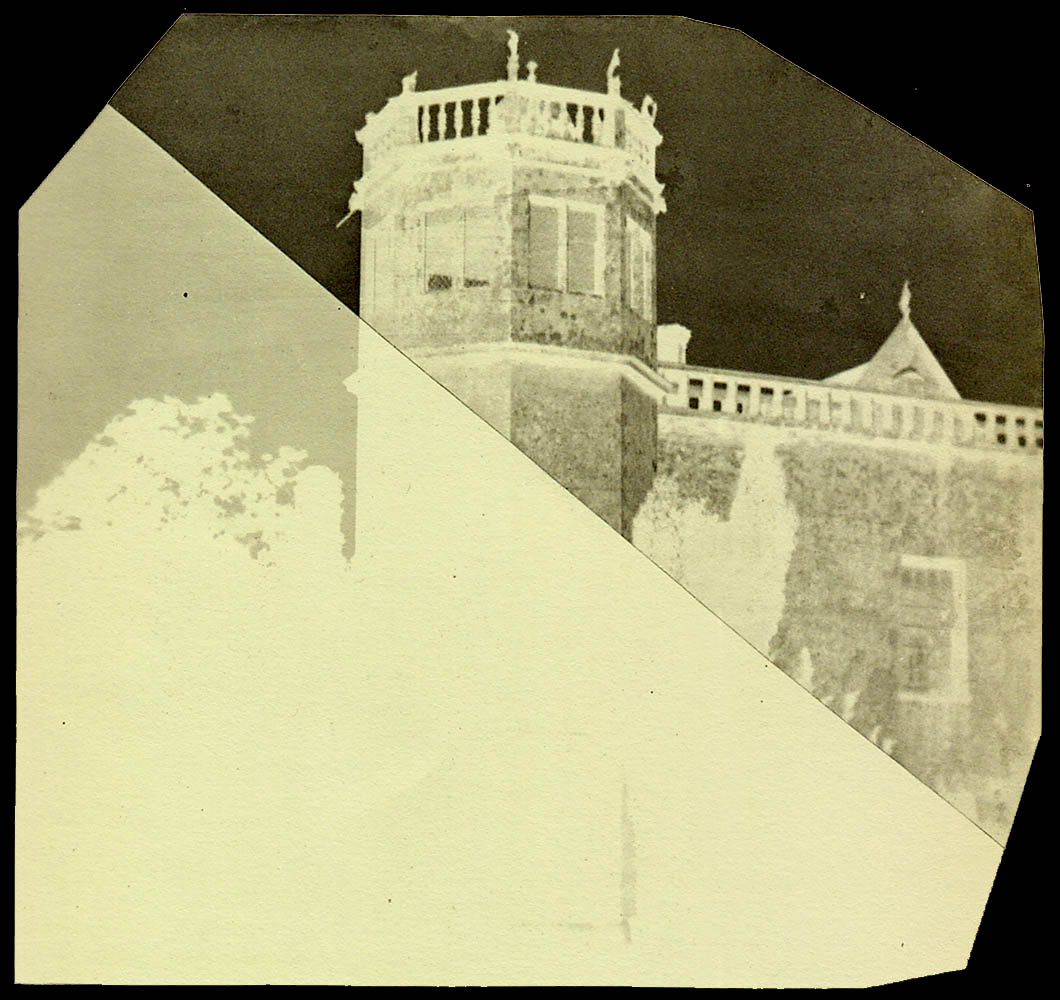

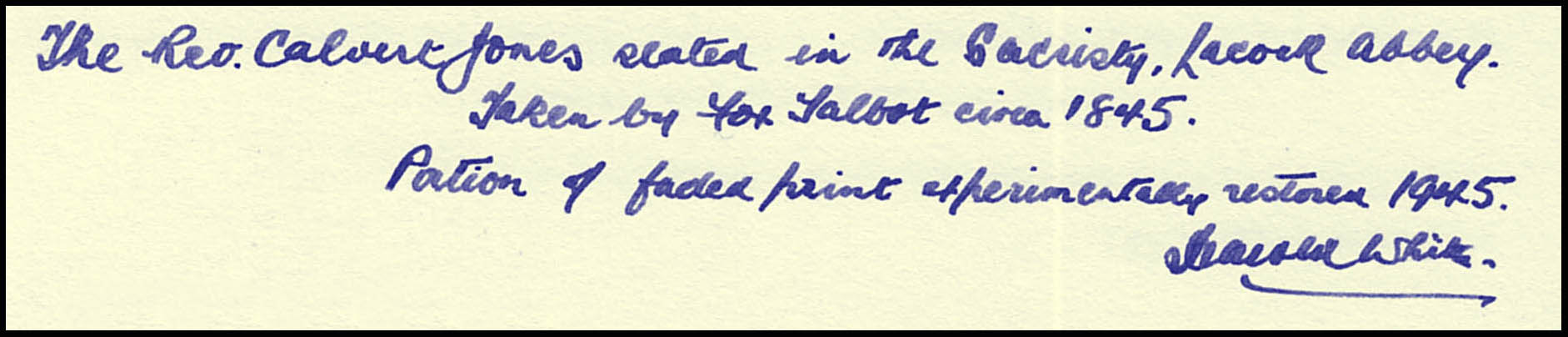

White worked to retrieve prints as well. A century after Talbot made this salted paper print, he proudly claimed to have ‘experimentally restored’ it. This print and the negative above actually started out physically and chemically the same. Talbot could have cut the same sheet of sensitive paper in half and made the negative on one portion and this print on another. The difference came in fixing – the negative was stabilized with potassium iodide and this print was fixed with hypo. The causes for fading were different in these two cases, something White understood very well, so he adopted a different approach here. He appended a typewritten note to this example explaining that he used Kodak’s IN-5 Silver Intensifier (a common solution that just might be familiar to some of our older readers) and suggested that “it will be seen that this method was quite successful.” And it remains so to this day, more than seventy years later.

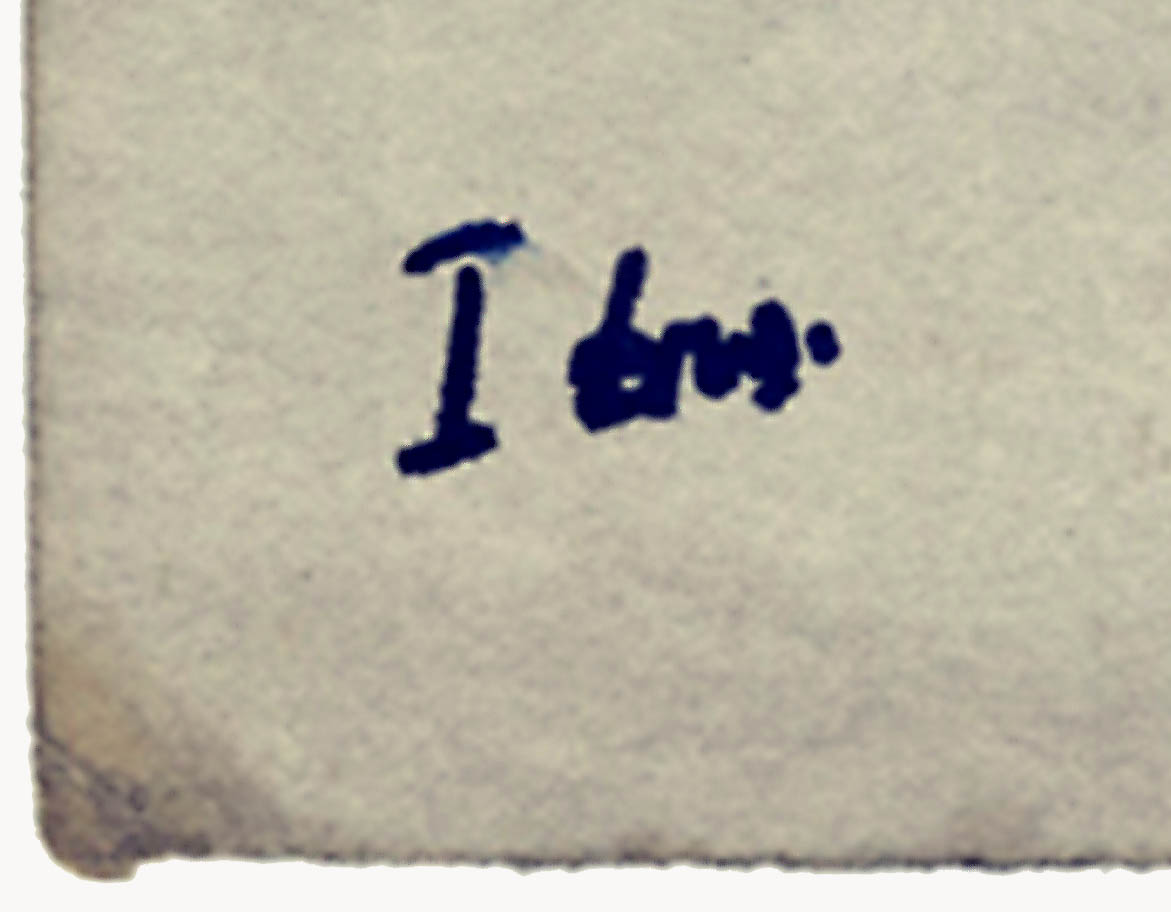

Perhaps because he was proud of his work, perhaps because he was a collector who knew that future market values could be affected by his transformations, White was absolutely scrupulous about permanently marking the originals that he had worked on. The ‘I HW’ in indelible ink helps to identify these. Similar markings occur on these three examples and on every other one that I have seen. Harold White was a complicated figure, working in a period when there were no established customs or rules. In his restoration work, he had the good fortune of being unaffected by market forces that had yet to evolve.

Perhaps because he was proud of his work, perhaps because he was a collector who knew that future market values could be affected by his transformations, White was absolutely scrupulous about permanently marking the originals that he had worked on. The ‘I HW’ in indelible ink helps to identify these. Similar markings occur on these three examples and on every other one that I have seen. Harold White was a complicated figure, working in a period when there were no established customs or rules. In his restoration work, he had the good fortune of being unaffected by market forces that had yet to evolve.

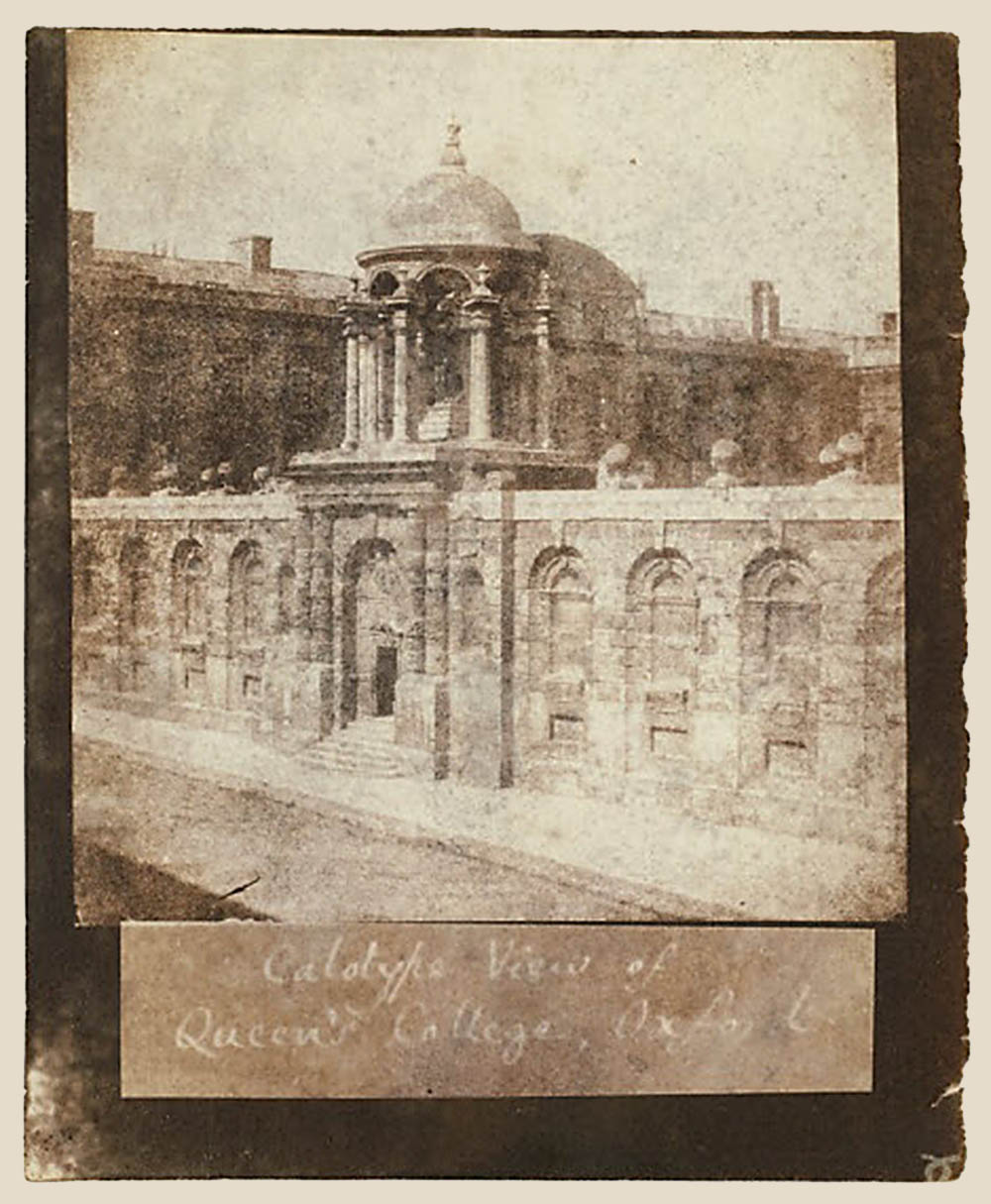

Finally, although it takes us away from Harold White long before this story is exhausted, it might be worth mentioning that there are a few examples of this photographic captioning similar to the rare example above.

In order to make these labels, Talbot wrote out the text in ink on a sheet of paper, then waxed it for transparency and used these in one of two ways. In the case of Queen’s above, he simply placed the ink label on the same sheet of paper as the photographic negative and printed them simultaneously. In the example on the right, he would have flipped the label over and created a photographic negative by printing it by contact on a sheet of photogenic drawing paper. This photographic negative could be used to make prints. which presumably would have been trimmed and mounted on the same board as the main photographic print. Although one might at first assume that these captions were done by Henneman for his print sales, they are written in Talbot’s hand. Were they an experiment? Were these done in the mid-1840s, contemporaneous with the photographic negative, or the early 1850s, whcn Talbot made up some small albums for personal use? Or were these labels made up for a special exhibition? I hope for the latter and for a review turning up some day of how people were reacting to this new art.

Larry J Schaaf

Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Paul Godfrey kindly contributed the tripod and camera self-portraits – see his ode to Harold White’s Lacock. Paul has closely examined his print and believes that the Rolleiflex dates from 1939-1949. It is badged ‘Franke & Heidecke’ and the focusing hood is of the early type lacking a sportsfinder. The Carl Zeiss lens is a 75mm f3.5 and is a double bayonet model, taking a filter on the viewing as well as the taking lens. These specs match the Rollei Automat model 2 (K4B), manufactured from 1939 to 1945, or the nearly identical Model 3 (K4B2) , produced from 1945 until 1949. Of course this provides only the earliest possible dating, for Harold might have had the camera a long time or may even have acquired a second hand one when the portrait was made. • An amalgamated transcription of Harold White’s various drafts, along with additional information on him and his collection, can be found in my Sun Pictures Catalogue Three: The Harold White Collection of Works by William Henry Fox Talbot (New York: Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, 1987). • Harold White, Matilda Talbot at Lacock Abbey, holding her copy of The Pencil of Nature, silver bromide print, ca. 1950, private collection. • Harold White, Self portrait at Lacock Abbey, silver bromide print, ca. 1950, private collection. • Harold White, Sundry Notes, Doubtful Importance, undated manuscript wrapper, Manuscripts Division, the British Library, London, Add MS 88942/9/1. • Harold White, Self Portrait with a Rolleiflex, silver bromide print (can some reader date this from the camera?). • WHFT, The Oriel Window, South Gallery, Lacock Abbey, probably 1835, Photogenic drawing negative, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Rubel Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee and Anonymous Gifts, 1997 (1997.382.1), Schaaf 1100. • WHFT, Tower from Urn, photogenic drawing negative, 31 May 1840, restored by Harold White; courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, New York; Schaaf 2438. • WHFT’s notebooks P and Q are in the National Media Museum, Bradford; their pages are reproduced in full facsimile and transcription in my Records of the Dawn of Photography: Talbot’s Notebooks P & Q (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). • WHFT, The Ancient Vestry: Calvert Jones in the Sacristy, Lacock Abbey, salt print from a calotype negative, 9 September 1845, restored by Harold White; courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, New York; Schaaf 1913. • WHFT, Queen’s College Oxford, with photographic label, salt print from a combination of a calotype negative and a photogenic drawing negative, 1843-1845; intensified by Harold White; Schaaf 220. Provenance unknown; this is currently being offered by Bernard Quaritch, Ltd, London, in their catalogue The Photographic Process; Creation, Dissemination and Conservation. • Harold White, I HW, ink inscription on the verso of an intensified salt print, private collection. • WHFT, Label for use as a negative, ink on paper, waxed, mid 1840s?, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-4459, Schaaf 3885. • WHFT, Photographic label, salt print from a manuscript master, mid 1840s?, Photographic History Collection, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1908-A; Schaaf 4782. In addition to being unusual, this is one of their earliest Talbot holdings, having been donated by Charles Henry Talbot in 1908.