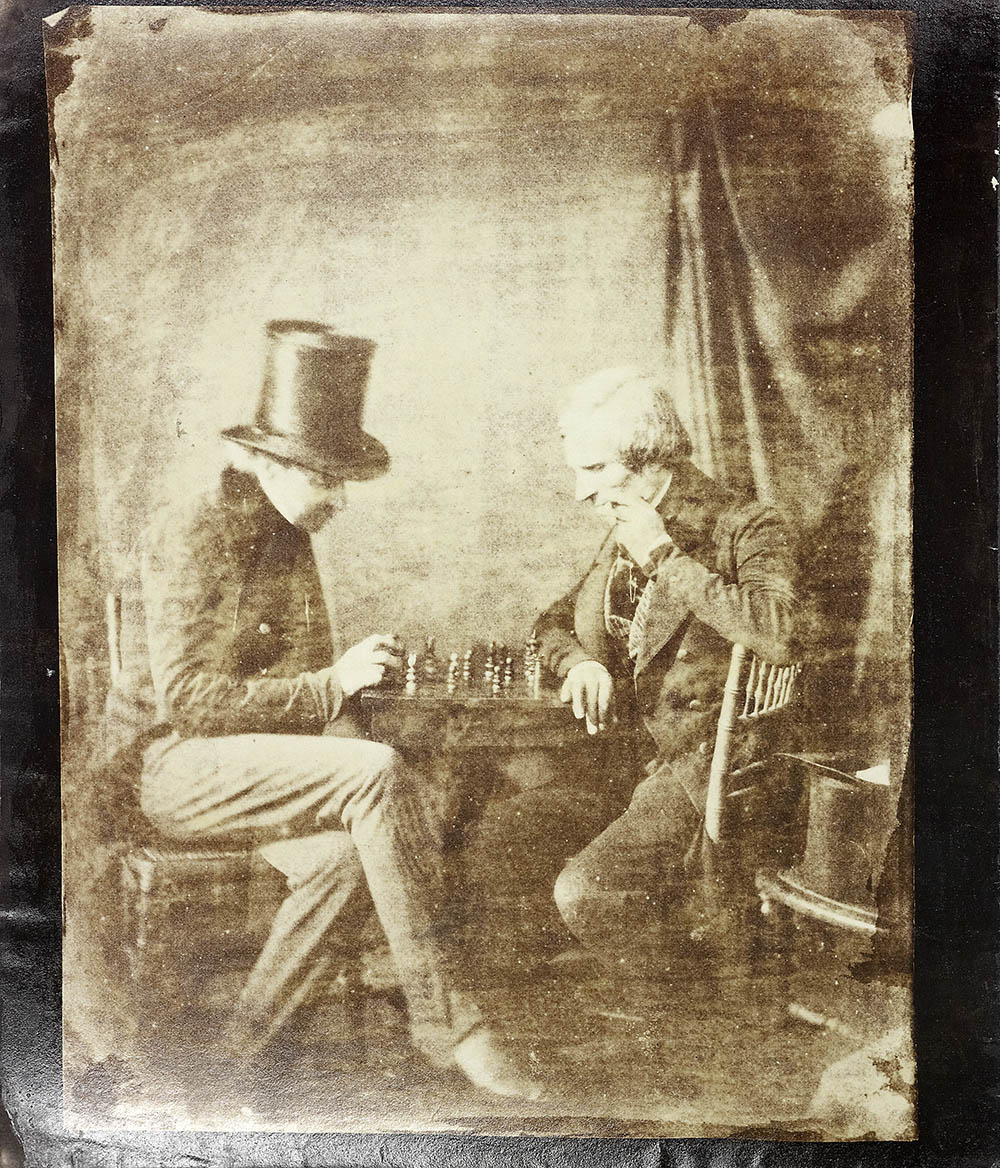

Some of the most widely-reproduced and universally admired ‘Talbot’ photographs are this brace of The Chess Players. The silver-haired scientific friend of Talbot, Antoine Claudet, faces off against a yet to be identified opponent (more on that person in a moment). The studio setting is simple, the lighting dramatic, the expressions believable and real. These are lively and authentic-looking portraits, worthy comparison to the best spontaneous portraits by Hill & Adamson.

I offset ‘Talbot’ in quote marks because as much as I would like these to have been taken by Henry, I just don’t see any way to justify this attribution. In addition to photographs provably taken by Talbot, the Catalogue Raisonné incorporates images made by his close circle as well as those traditionally associated with him. There remains considerable ambiguity about the attribution of many ‘Talbot’ images, some of which we hope to resolve by the intersections created within the project and by crowd-sourcing fresh information. And to be fair, the attributions published in the past, correct or not, still have guided the course of scholarship and criticism over the years and must be recognised.

One aphorism from the great chess master Savielly Tartakower was that “some part of a mistake is always correct.” So in that spirit, what do we actually know about these images?

One confirmed data point comes from Nicolaas Henneman’s 1847 Talbotypes or Sun Pictures, where the final print is the Chess Players. So far as is known, this is a unique copy of this folio, a proof copy for a publication never realised. However, it gives us half of a set of bookends in the form of a late date and it firmly establishes the connection between this image and Henneman. Even if Talbot had not seen The Chess Players previously, surely Henneman shared this ode to The Pencil of Nature with him.

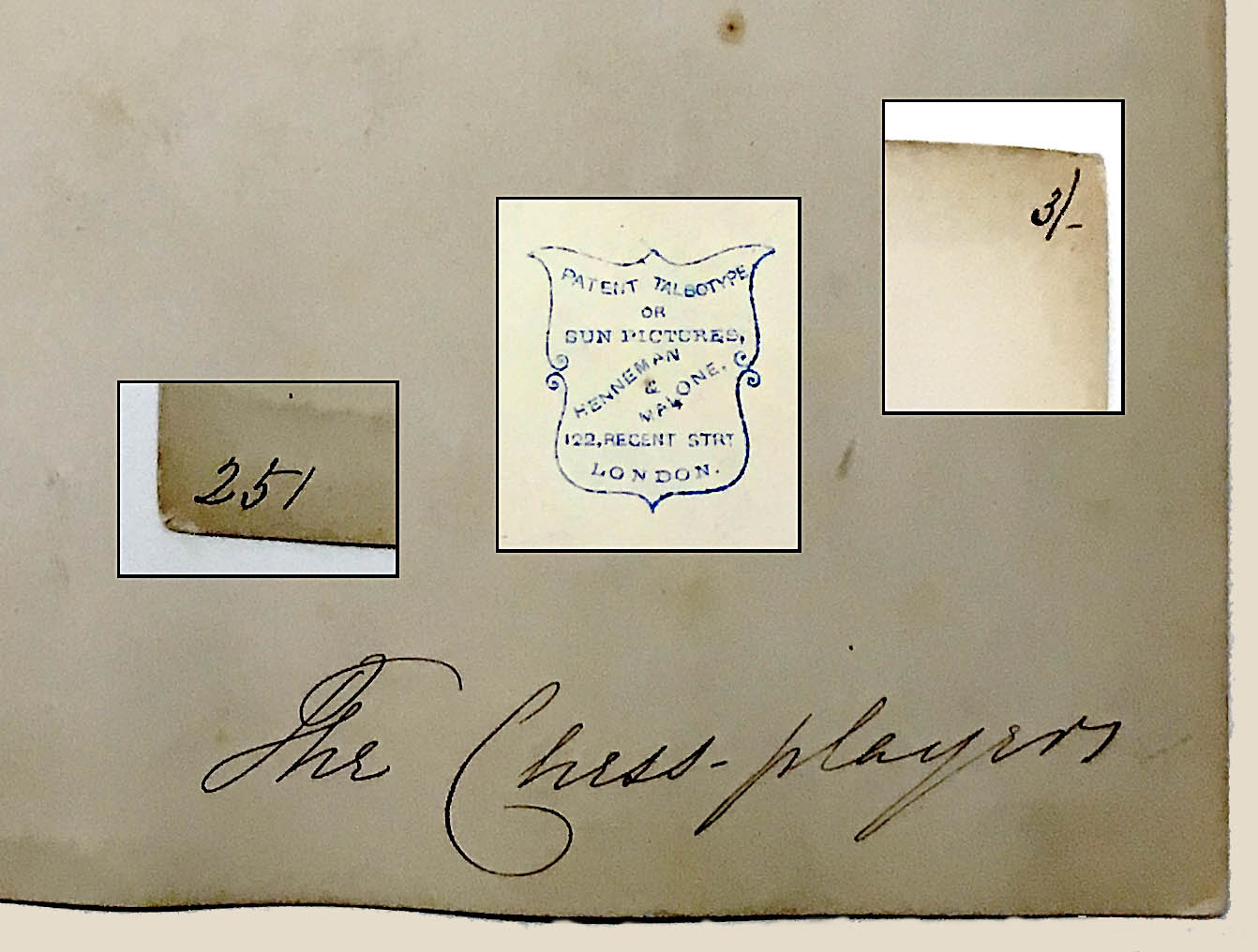

A few of the Chess Players prints have stamps or markings on the mount, more typically on the verso, that establish that they were ones that Henneman or a bookseller offered for sale. The ‘251’ here was Henneman’s inventory number, 3/ the price of three shillings, and the Henneman & Malone stamp establishes this as a print offered for sale during their formal partnership in London from 1847-1851. And that just about exhausts our definite knowledge. Neither of these negatives is known to have survived and of the numerous prints of these two photographs preserved worldwide, none has any reliable inscription or early provenance. None that I know of has any links to a collection during Talbot’s lifetime, or indeed any provenance before Matilda Talbot started her distributions in the 1930s.

A few of the Chess Players prints have stamps or markings on the mount, more typically on the verso, that establish that they were ones that Henneman or a bookseller offered for sale. The ‘251’ here was Henneman’s inventory number, 3/ the price of three shillings, and the Henneman & Malone stamp establishes this as a print offered for sale during their formal partnership in London from 1847-1851. And that just about exhausts our definite knowledge. Neither of these negatives is known to have survived and of the numerous prints of these two photographs preserved worldwide, none has any reliable inscription or early provenance. None that I know of has any links to a collection during Talbot’s lifetime, or indeed any provenance before Matilda Talbot started her distributions in the 1930s.There is one more fly that we can land in this ointment. Many of these prints are not on the Whatman’s paper typical of Talbot’s and Henneman’s printings, but rather on a noticeably thicker unwatermarked paper. In addition, many have wide white bands on the edges (similar to those created by print easels, for the dwindling number of us who remember the darkroom days). One immediately thinks of the possibility that some of these prints were made later, perhaps after Talbot’s lifetime and sometime before Miss Talbot began distributing them in the 1930s. In fact, one example has been cut apart for what appeared to be some sort of testing and then re-assembled. When I first saw the face of this I got all excited, thinking that surely somebody must have been researching the heavy paper. But upon turning it over, I saw that they were testing the effects of intensification (this specimen was not handled by Harold White).

So what about the image idea itself? While there are numerous references to chess playing in Talbot’s correspondence, nothing is useful for tying him to these particular images. Not including the famous two above, there are at least a dozen Talbot portraits of chess players, the earliest dated September 1841 (the day was lost in a subsequent trimming of the negative). Others are dated 7 April 1842 and July 1842.

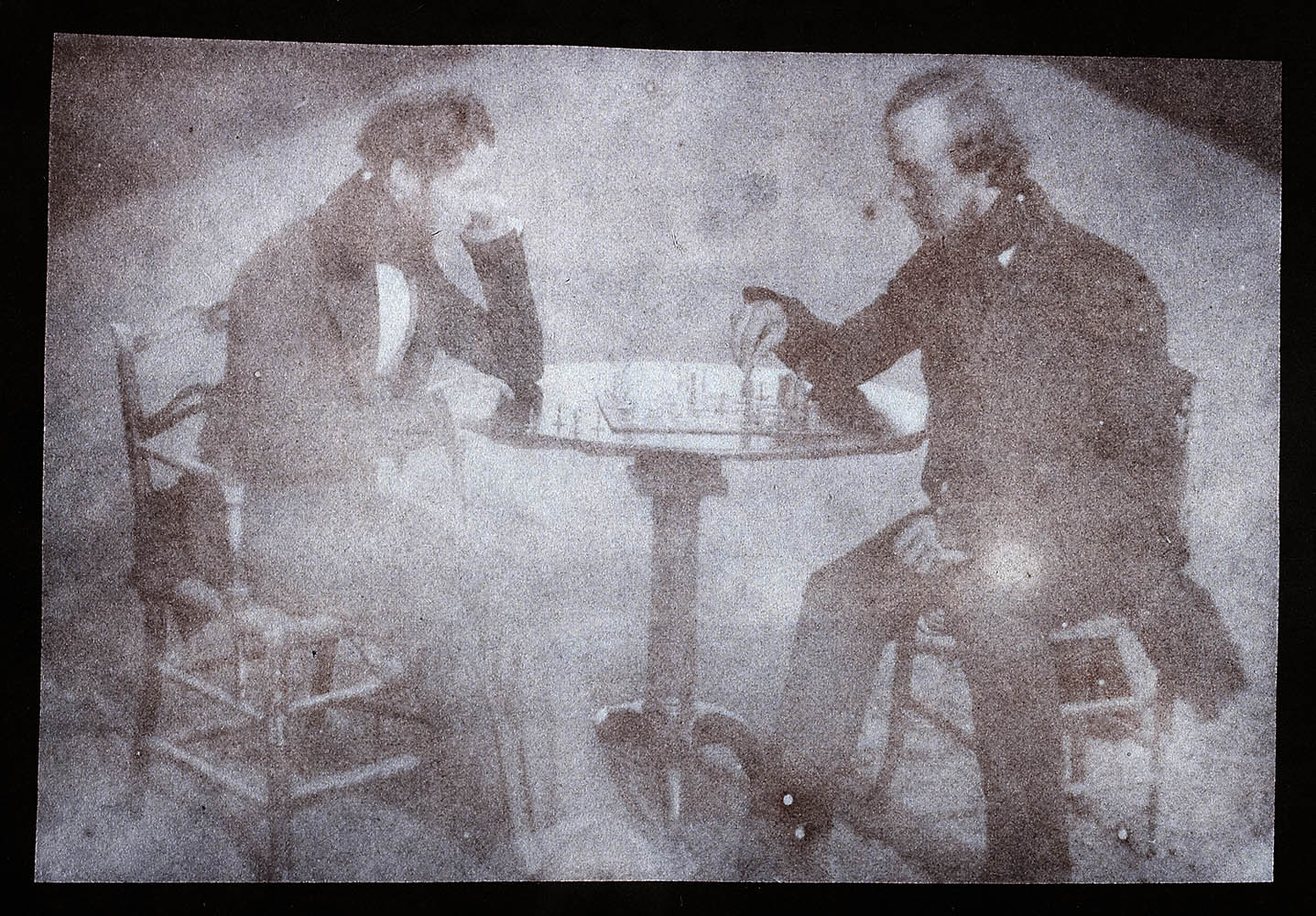

Did Nicolaas Henneman himself play chess? He is depicted in the majority of these images. Here a bed sheet has been draped up outdoors, isolating the background while taking advantage of the sun. This might date from September 1841, when a similar image was taken, but the negative was subsequently drastically trimmed down, making it a portrait of a contemplative Henneman rather than a competitive match. Any dates or other inscriptions fell victim to the shears.

The distinctive oversize head (what would phrenologists make of that?) of John Frederick Goddard provides a tentative dating for this one. As Lady Elisabeth recorded in her diary, the London daguerreotypist and chemist visited Lacock Abbey from 7-9 April 1842 in order to learn paper photography and it is reasonable to assume that this picture was taken in one of their sessions. Nicolaas Henneman again takes up one side of the board. Instead of an artificial backdrop, Talbot has cleverly employed an elevated camera angle (a spectator’s eye view) and careful placement of a gravel path to isolate the figures. Given that Henneman had become accustomed to these scenes at Lacock Abbey, is it reasonable to assume that he was the photographer of the well-known Chess Players images? Stylistically I don’t think so, for as much as I admire Henneman’s courage, he never really mastered the aesthetics of the art as well as he should have.

So just who did Claudet face off against in his chess battle? Fortunately there is a tantalizing clue.

At some point Henneman had large sheets of type set to make labels for the prints he had for sale. Typically they were used like the example upper right, in this case on the recto of the mount below the photograph, more often on the verso of the mount. These replaced the manuscript titles like the one shown earlier and were probably intended to convey a more professional appearance. It is clear that Talbot himself knew about them – they might even have been his idea. The ‘Orleans’ above is in his hand, meaning that this was not a commercially sold print but rather one that he presented to someone, enhanced by Henneman’s label. More importantly, there is one set of these uncut sheets that Talbot must have used as a master index, for it is annotated with prices and other information. The Chess Players carries his notation that “M. leaning on his hand,” identifying it as the more favoured left hand version.

So who was ‘M.’? This is far too early for one of Judi Dench’s predecessors, long before MI6 was founded. Talbot corresponded with nearly a hundred M surnames. Some can be eliminated by age or geography. Could it have been John Murray, his publisher? Thomas Malone was too young. The poet Thomas Moore of too small a stature. Perhaps Robert Murray, the Irish optician and photographer who worked in close proximity to Henneman on Regent Street? Possibly even Talbot’s artist friend George Montgomerie?

So, the simple beauty and strength of The Chess Players conceal a number of secrets, appropriate for a depiction of a game so complex, and a figure so complex as Antoine Claudet, a true gentleman, a fine artist, a successful entrepreneur and a master of many areas of science.

Kudos to anyone who can identify ‘M’. Perhaps those more familiar with the game of chess can derive some meaning from the placement of the pieces here? Any leads welcome.

Kudos to anyone who can identify ‘M’. Perhaps those more familiar with the game of chess can derive some meaning from the placement of the pieces here? Any leads welcome.Larry J Schaaf

Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Circle of WHFT, attributed to Antoine Claudet, The Chess Players, Claudet on the left, salt print from a calotype negative, ca. 1845; National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-372-1; Schaaf 2819; Circle of WHFT, attributed to Antoine Claudet, The Chess Players, Claudet on the right, salt print from a calotype negative, ca. 1845; Tekniska museet (National Museum of Science and Technology), Stockholm, 21-87-6; Schaaf 2820. • Nicolaas Henneman, Talbotypes or Sun Pictures, Taken from the Actual Objects They Represent (London: Nicolaas Henneman, 1847) National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2530/24, Schaaf 2819. • Markings on the verso of a mounted Chess Players, courtesy of Hans P. Kraus, Jr., Inc., New York. • Detail of heavy paper edge with white band on a print of The Chess Players, Tekniska museet, Stockholm, 21-87-6; Schaaf 2820. Detail of a cut apart, intensified and re-assembled salt print of The Chess Players, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elishas Whittelsey Collection, the Elishas Whittelsey Fund, 1973.616, Schaaf 2819. • WHFT, A Gentleman Challenging Nicolaas Henneman in a Game of Chess, salt print from a calotype negative, ca. 1842, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, LA2110, Schaaf 975. WHFT, Cut-down Negative of Nicolaas Henneman Contemplating a Chess Board, calotype negative, ca. 1842, 1937-3862, National Media Museum, Bradford, Schaaf 975. • WHFT, Nicolaas Henneman Challenging John Frederick Goddard in a Game of Chess, salt print from a calotype negative, probably 7-9 April 1842, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-366/1/57, Schaaf 1496. • Circle of WHFT, attributed to Antoine Claudet, The Chess Players, Claudet on the right (printed before the negative was trimmed down), varnished salt print from a calotype negative, ca. 1845, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2526/12, Schaaf 2820. • Detail of The Chess Players, Claudet on the right, salt print on heavy paper from a calotype negative, ca. 1845; Tekniska museet, Stockholm, 21-87-6; Schaaf 2820. • Nicolaas Henneman, Uncut Printed Sheet of Captions, National Media Museum, Bradford. WHFT, detail of The Principal Place in the City of Orleans, From Nature, 1843; mounted salt print from a calotype negative, 14 June 1843, courtesy of Hans P. Kraus, Jr., New York; Schaaf 1707. Nicolaas Henneman, detail of Uncut Printed Sheet of Captions, Fox Talbot Collection, Manuscripts Division, The British Library, London.