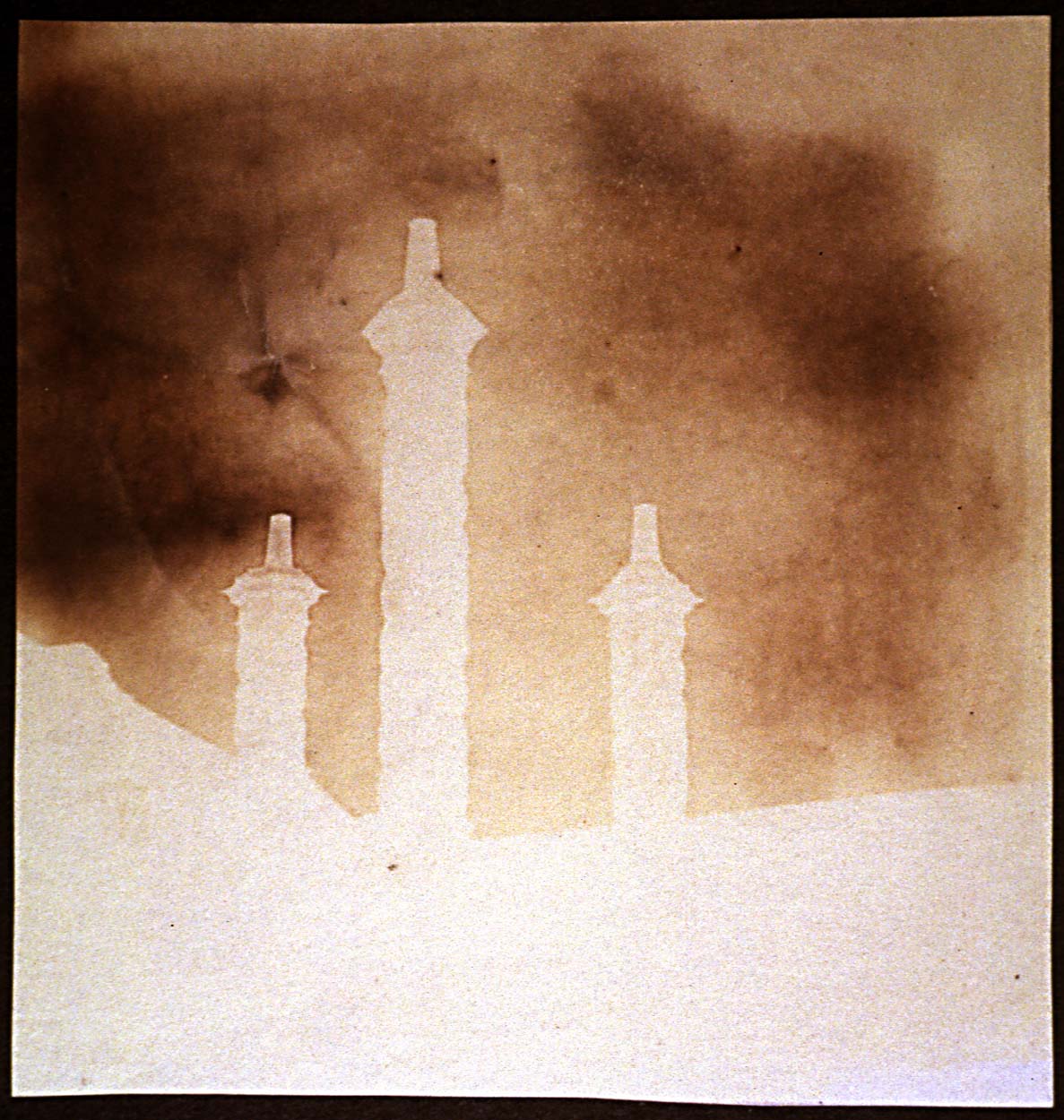

Last year about this time we celebrated the 175th birthday of the Calotype. This was Talbot’s discovery within a branch of his exploratory research that he could build on the existence of a latent image. In his first process, photogenic drawing, the sun had to do all the work of reducing the light sensitive silver salts to the metallic silver clusters that formed the visible image. In the calotype, a brief exposure in the camera left behind an invisible latent image. Later, in the darkroom, the application of a chemical developer magnified the sun’s original action by a factor of thousands of times. The briefest of exposures could be leveraged into a full strength image. The concept of the calotype, applying a developer to a latent image, was the pattern that would be followed subsequently right down to the digital age. So let us once again light the metaphoric candles.

Last year about this time we celebrated the 175th birthday of the Calotype. This was Talbot’s discovery within a branch of his exploratory research that he could build on the existence of a latent image. In his first process, photogenic drawing, the sun had to do all the work of reducing the light sensitive silver salts to the metallic silver clusters that formed the visible image. In the calotype, a brief exposure in the camera left behind an invisible latent image. Later, in the darkroom, the application of a chemical developer magnified the sun’s original action by a factor of thousands of times. The briefest of exposures could be leveraged into a full strength image. The concept of the calotype, applying a developer to a latent image, was the pattern that would be followed subsequently right down to the digital age. So let us once again light the metaphoric candles.

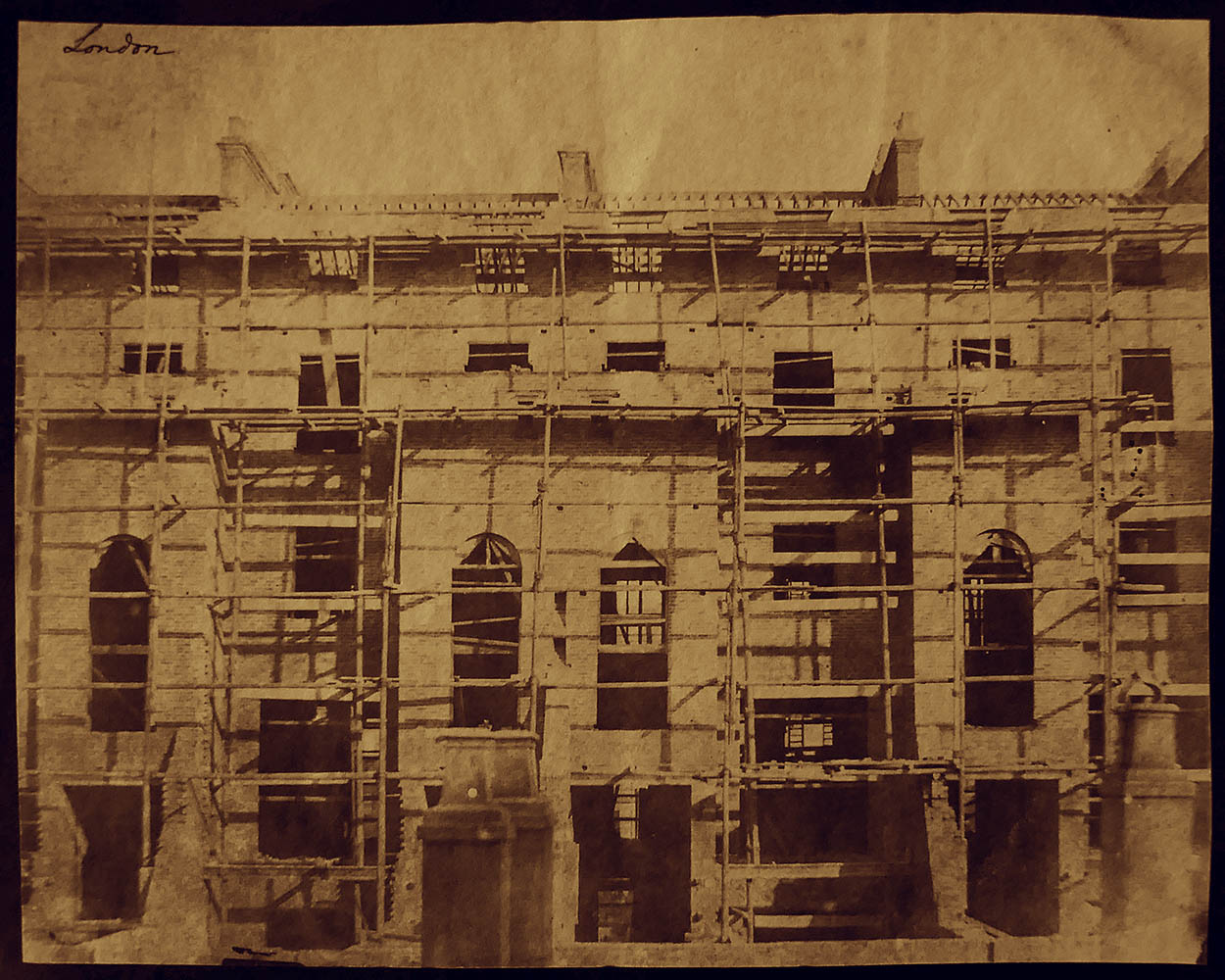

House Building in Sussex Gardens

Since we are celebrating the anniversary of the calotype this week, I turn to one of my favourite calotype negatives – a favourite because its apparently simple but enigmatic nature has caused me so much delightful trouble over the years.

Now, one would think that this was pretty straightforward, but where would be the fun in that? On 1 June 1844, Henry recorded in his diary that he journeyed up to London, staying at “32 Sussex Gardens, Hyde Park.” The following year, Lady Elisabeth recorded in her diary: “7 June [1845] Henry went to live in Sussex Gardens.” The area was clearly productive for him. We have already seen his evocative image of the building of the now-destroyed Holy Trinity Church in Paddington. The temporary terminus for Brunel’s Great Western Railway opened in 1838, presaging an explosive growth of development for the area. The station that we (and the Bear) are familiar with today dates from 1854, but a decade earlier than that the rapid evolution of a new urban complex fascinated Talbot. Indeed, the majority of his photographs of the built environment depict change, even many of those that look ancient to us. Although he was a NIMBY, fighting Brunel’s idea of running a rail line through Lacock, Henry loved the railways and was excited when the line could carry him up to London. Always interested in the new and in change, it was natural that he should carry his cameras with him.

Nicolaas Henneman wrote to Henry on 25 January 1845 making reference to the “negative of the house building with the Scaffolding on it.” Henneman’s printed title list no. 15 is “A House Building in London, 1844” so I think that we can pretty safely assume that this negative dates to Talbot’s first recorded visit to Sussex Gardens. When Lady Elisabeth made a present of some of her son’s photographs to her friend, the Duke of Devonshire, she called this image “A House Building in Sussex Gardens.” It is still preserved at Chatsworth, titled in ink on its mount. “Sussex Gardens Hyde Park.”

I suspect that many of our readers have stayed at one of the numerous small hotels that line the long street of Sussex Gardens – they are an easy walk from Paddington Station, the entry point from Heathrow Airport and Bath and the village of Lacock, via Chippenham. Those sometimes vexing but useful little hotels almost perished in the 1970s, when 54 of them on the north side of the street were to be sacrificed to clear the way for six mega-hotels. Fortunately the planners did the right thing that time and denied the permits. But Sussex Gardens was in fact a much more limited street until comparatively modern times. Until 1938, the majority of it was known as the Great Western Road.

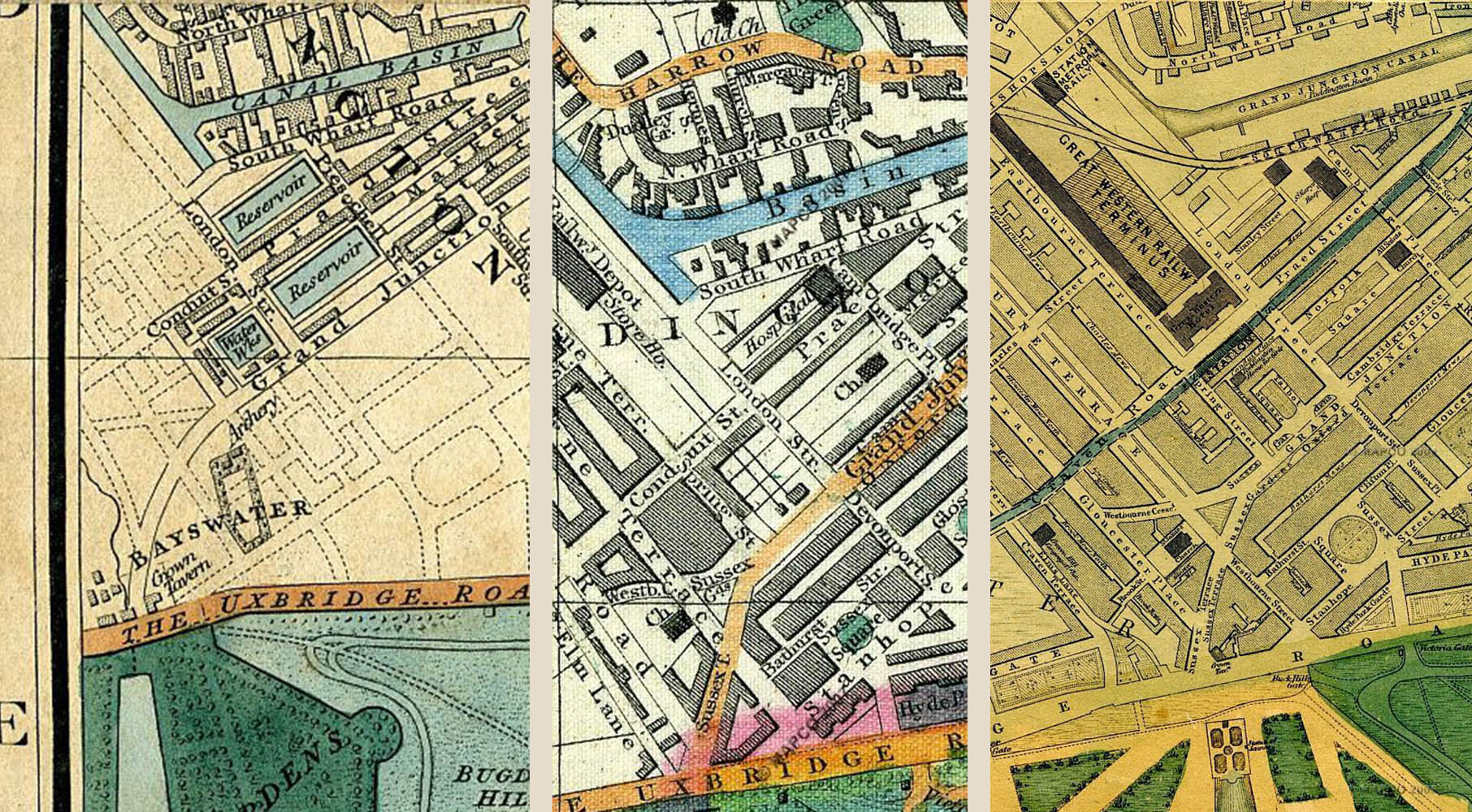

I suspect that many of our readers have stayed at one of the numerous small hotels that line the long street of Sussex Gardens – they are an easy walk from Paddington Station, the entry point from Heathrow Airport and Bath and the village of Lacock, via Chippenham. Those sometimes vexing but useful little hotels almost perished in the 1970s, when 54 of them on the north side of the street were to be sacrificed to clear the way for six mega-hotels. Fortunately the planners did the right thing that time and denied the permits. But Sussex Gardens was in fact a much more limited street until comparatively modern times. Until 1938, the majority of it was known as the Great Western Road. The area had traditionally been known as Triburnia, after the notorious three legged gallows at Tyburn Tree (tripod) which was in active use until end of 18th century. The 1843 death of Prince Augustus Frederick, brother of George IV, the Duke of Sussex precipitated the change of name. The above composite map shows the area in 1837, 1851 and 1868. Pick out the little triangle at the left; that enclosed Sussex Square and was the limit at the time of the street named Sussex Gardens.

The area had traditionally been known as Triburnia, after the notorious three legged gallows at Tyburn Tree (tripod) which was in active use until end of 18th century. The 1843 death of Prince Augustus Frederick, brother of George IV, the Duke of Sussex precipitated the change of name. The above composite map shows the area in 1837, 1851 and 1868. Pick out the little triangle at the left; that enclosed Sussex Square and was the limit at the time of the street named Sussex Gardens. The arched windows of the brace of hotels either side of this square match those depicted in Talbot’s building photograph – they are the only ones along the current Sussex Gardens to do so – but sadly, Talbot Square (named for a different Talbot family, by the way) was not established until it replaced the Lower Reservoir, abandoned and drained around 1860, long after Talbot’s photograph. So we must turn to Sussex Gardens as it was delineated in the mid 19th century in the maps above.

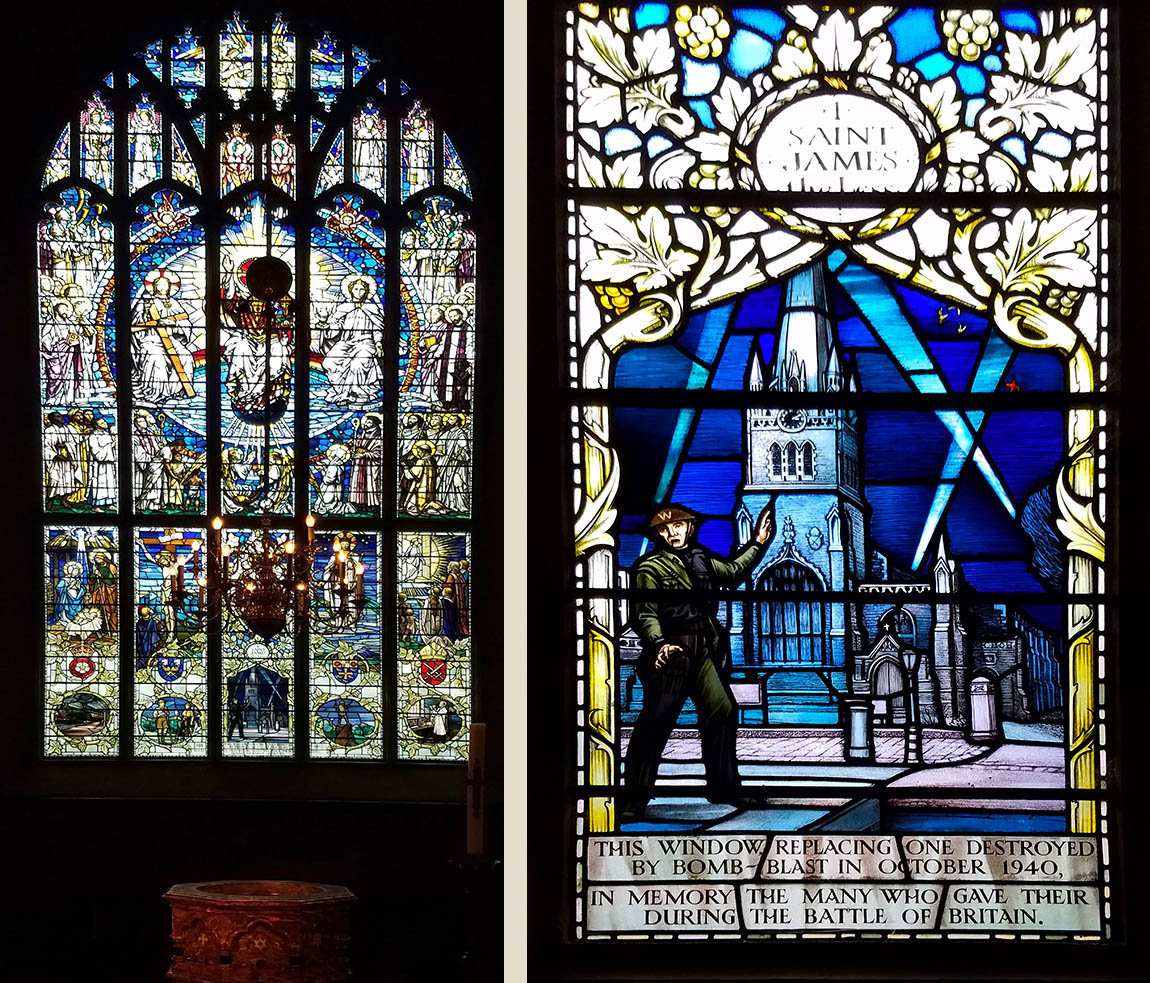

The arched windows of the brace of hotels either side of this square match those depicted in Talbot’s building photograph – they are the only ones along the current Sussex Gardens to do so – but sadly, Talbot Square (named for a different Talbot family, by the way) was not established until it replaced the Lower Reservoir, abandoned and drained around 1860, long after Talbot’s photograph. So we must turn to Sussex Gardens as it was delineated in the mid 19th century in the maps above. But there is a complication. I have seen several otherwise traditional Afghan rugs depicting helicopters and tanks, but even so I must admit that the Baptistry window in St James on Sussex Square was a surprise to me. In October 1940, a parachute mine drifted past its intended target of Paddington Station and demolished the spire and much of interior of St James, the parish church for Paddington. Amazingly, the church continued to function under tarps throughout the war and was restored afterwards. While there have been changes to the interior, the front façade looks exactly like it did in the woodcuts of the 1840s.

But there is a complication. I have seen several otherwise traditional Afghan rugs depicting helicopters and tanks, but even so I must admit that the Baptistry window in St James on Sussex Square was a surprise to me. In October 1940, a parachute mine drifted past its intended target of Paddington Station and demolished the spire and much of interior of St James, the parish church for Paddington. Amazingly, the church continued to function under tarps throughout the war and was restored afterwards. While there have been changes to the interior, the front façade looks exactly like it did in the woodcuts of the 1840s. For those readers better versed in wartime or local history than I, it would be really helpful to see photographs of this end of Sussex Square either before the war or in the aftermath of the Blitz’s destruction. Please come forward if you know of any.

For those readers better versed in wartime or local history than I, it would be really helpful to see photographs of this end of Sussex Square either before the war or in the aftermath of the Blitz’s destruction. Please come forward if you know of any.

So, that narrows our current candidate to the building on the south side of St James church, towards Hyde Park.

Admittedly it is higher than the building that Talbot photographed under construction, but it would not be unusual for buildings to have been extended upwards as the value of properties in central London increased (the fashion nowadays is to build downwards, adding subterranean swimming pools &c, often much to the consternation of more traditional neighbors). For what is known at present, I think that this building at 237-239 Westbourne Terrace (as it is now styled) is most likely the subject of Talbot’s 1844 calotype negative.

And what a negative it is! How often do we get to see evidence of the process of change and evolution of more than a 170 years ago? For many areas of our cities, our documents are lacking from 170 months ago, sometimes even 170 weeks ago. In addition to being a fascinating and intriguing calotype negative, Talbot’s depiction is an unusual survivor of architectural history.

In Memoriam

In Memoriam

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, Three Chimnies (Large), calotype negative, 7 October 1840, Photographic History Collection, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1995.206.109; Schaaf 2495. • WHFT, A House Building in Sussex Gardens, calotype negative, summer 1844, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-3952; Schaaf 1198. • Nicolaas Henneman to WHFT, 25 January 1845, Talbot Correspondence Project Document no. 05167. • WHFT, A House Building in Sussex Gardens, salt print from a calotype negative, summer 1844, Kornik Museum, Polska Akademia Nauk, Kornik, Poland; Schaaf 1198. • Details of Cross’s 1837 Map of Paddington, Cross’s 1851 and Weller’s 1868; courtesy of and © of MAPCO : Map And Plan Collection Online.