Guest post by Jaanika Vider

To continue with the fruity theme started in last week’s Summer Pleasures, I will turn my attention to a more tropical species. For some weeks now, pineapples, which are native to South America, have piqued my interest. The initial fascination was triggered by a wonderful course taught at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford by Dr Jim Harris, titled ‘Eloquent Objects‘. One of the objects used in this course was a ceramic bowl with a pineapple motif; while the bowl itself was rather unremarkable, the stories it evoked about class, status, and colonial encounters were poignant.

From that point on, I started seeing pineapples everywhere – on interior columns of the Natural History Museum in Oxford, on top of St Paul’s Cathedral in London, as ornamentations on various museum objects and on shelves of many gift shops. Not surprisingly the exotic Ananas comosus also crops up in several photographs in the Catalogue Raisonné.

The most obvious and well-known is of course Plate XXIV. ‘A Fruit Piece’ in The Pencil of Nature.

The star of this still life is really quite obviously the pineapple, centred in the frame and kept company by a quantity of apples (and what looks like a peach in the basket on the right). Indeed, the same pineapple is photographed on its own in Schaaf number 1503 arranged in a different basket but on the same table with a tartan table cloth.

We know little about the time these photographs were taken apart from it being before 23 April 1846 when the sixth fascicle of The Pencil of Nature was issued. Searching the Talbot correspondence yielded no clues but it is a reasonable guess that the photograph would have been arranged in late summer when the fruit were most likely to be in season.

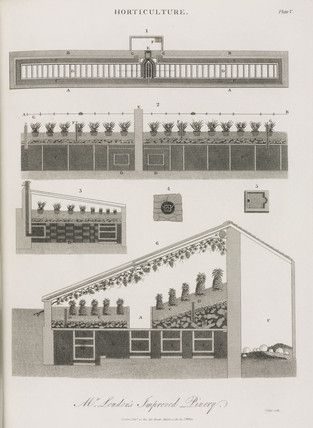

The pineapple is likely to have been grown in the British Isles in a purpose built pineapple pit (in 2013 one such pit was restored in the Lost Gardens of Heligan in Cornwall). These began to be set up in the first half of the 18th century after importing cultivation methods from Holland. The growing of pineapples was a way to cater to the desire of the upper classes to taste the exotic fruit whose fame, rarity, and expense made it a well-recognised but seldom experienced good in the 17th and 18th century (those less wealthy but aspirational could rent a pineapple to display at dinner parties only for the fruit to be eaten by the more elite still!). However, pineapple cultivation was also a display of scientific knowledge and technological advance to be able to overcome nature and coax the plant to yield fruit in colder climates. Ruth Levitt writes in Garden History:

The pineapple is likely to have been grown in the British Isles in a purpose built pineapple pit (in 2013 one such pit was restored in the Lost Gardens of Heligan in Cornwall). These began to be set up in the first half of the 18th century after importing cultivation methods from Holland. The growing of pineapples was a way to cater to the desire of the upper classes to taste the exotic fruit whose fame, rarity, and expense made it a well-recognised but seldom experienced good in the 17th and 18th century (those less wealthy but aspirational could rent a pineapple to display at dinner parties only for the fruit to be eaten by the more elite still!). However, pineapple cultivation was also a display of scientific knowledge and technological advance to be able to overcome nature and coax the plant to yield fruit in colder climates. Ruth Levitt writes in Garden History:

[I]n the course of the eighteenth century, pineapple cultivation in special hothouses became the expensive but fashionable pastime of a small though increasing number of horticultural enthusiasts among members of the gentry and nobility, who had the skilled gardeners and the money to indulge in this pursuit (2014: 110)

Talbot’s enthusiasm for Botany and the output of this interest in photographic medium has been discussed in previous project blogs by Professor Larry J Schaaf and Dr Stephen Harris. While there is no suggestion that Talbot dabbled in pineapple growing, the fruit were a discernible result of the type of scientific achievement pursued by earlier generations of men like Talbot. By the time these photographs were taken, the activity was undertaken by many professional gardeners and nurserymen, including the Henderson family at Pineapple place, Maida Vale from whom Talbot received seeds and plants. Johanna Lausen-Higgins further reports that Joseph Paxton, the head gardener to the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth house (1826-1858) was a particularly successful pineapple grower whose fruit ‘were the envy of every estate and won medals at horticultural shows’. We know that Talbots were visitors at Chatsworth house and Talbot photographs given to Duke of Devonshire are still found in its collections. Whether or not this pineapple came from the pinery at Chatsworth house, I do not know. While it certainly looks prize-worthy it may as well come from a fruitier in London, as even in 1822 Loudon reported:

Of late years the Pine Apple has been sent to England in abundance, attached to the entire plant, and a cargo has arrived from Providence Island, in the Bermudas, in six weeks. This facility of cultivation, and their more general culture, has greatly lessened their price, and rendered them common. They are sold in fruit-stands in the London streets, in one or two places, during the summer months; and moderate-sized fruit may be had from half-a-crown to a crown each; or at two shillings a pound. (Loudon 1822)

By the turn of the century, cultivation of pineapples in the UK became unprofitable as transportation of pineapples from the Caribbean became easier and pineapples increasingly common. However, the visual legacy of the ‘pineapple craze’ of previous centuries lives on around us. By the time the last fascicle of The Pencil of Nature was issued, the pineapple had already found its way into the seminal volume in the form of a vase in Plate III. “Articles of China.” or as described by Lady Elisabeth Feilding on the album page below, ‘Old Dresden China at Laycock Abbey’.

This same vase has also found its way onto paper in an arrangement with the Bust of Venus in Schaaf 2357 and other pieces of Dresden China captured in 1840 in Schaaf 2351 and Schaaf 237. The fact that there was a vase with a pineapple motif in Lacock Abbey speaks to the many other pieces of ceramics found in museums, galleries and auction houses across the world.

I finish here in Oxford, where the Pineapple on the gate tower of All Souls College foregrounds the view towards the Twin Towers of Hawksmoor. The pineapple is still there to be seen by many thousands of visitors to Oxford although I suspect that few notice it. Indeed, it is more difficult when one does not have the privilege of photographing out of the Radcliffe Camera, as Talbot did on this occasion. Nicholas Hawksmoor’s use of a stone pineapple to top the dome built in the early 18th century speaks to the practices of his mentor, Sir Christopher Wren, who famously adorned St Paul’s Cathedral and St John the Evangelist Church in London with pineapples. Wren was of course the architect of many buildings that were photographed by Talbot but I have not found other pineapples in our catalogue yet. I suspect searching for them might become a new hobby.

The distinctive look of the pineapple along with its history as an exotic and highly prestigious fruit firmly established its place in the European visual aesthetic. The invention of photography and subsequent proliferation of images of existing objects only went on to solidify it. Today the once elusive pineapple is so abundant that it is easy to forget that in Talbot’s time it still retained an air of significance both in art and science which made it a perfect subject for capture.

Jaanika Vider

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Lausen-Higgins, J. (2010). A Taste for the Exotic. Pineapple Cultivation in Britain. Historic Gardens. BCD Special Report. • Levitt, R. (2014). ‘A Noble Present of Fruit’: A Transatlantic History of Pineapple Cultivation. Garden History, 42(1), 106-119. • Schaaf 16, National Science and Media Museum. Science Museum Collection. 1937-1257/2 • Schaaf 1503, National Science and Media Museum, Science Museum Collection. 1937-2222/1 • Plate V in Loudon’s An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green, London, 1827 • Schaaf 68, National Science and Media Museum, Science Museum Collection. 1937-2535/3 • Schaaf 30, National Science and Media Museum, Science Museum Collection, 1937-1862/4