This summer’s flowers and leaves are fleeting and will fade in time. For that reason it’s strange to think that we can still see those flowers and leaves Talbot used many seasons ago to create his photogenic drawings of botanical specimens, sometimes rendered in incredible photographic detail. This week sees the welcome return of Dr. Stephen Harris, Druce Curator of Oxford University Herbaria to the Talbot project blog. Just before he set of on a field expedition to Brazil, Dr. Harris found the time to give us an added insight into Talbot, the Botanist and collector of botanical specimens.

This summer’s flowers and leaves are fleeting and will fade in time. For that reason it’s strange to think that we can still see those flowers and leaves Talbot used many seasons ago to create his photogenic drawings of botanical specimens, sometimes rendered in incredible photographic detail. This week sees the welcome return of Dr. Stephen Harris, Druce Curator of Oxford University Herbaria to the Talbot project blog. Just before he set of on a field expedition to Brazil, Dr. Harris found the time to give us an added insight into Talbot, the Botanist and collector of botanical specimens.

Brian Liddy

Guest Post by Dr Stephen Harris

Guest Post by Dr Stephen Harris

In early May, a few days after getting back from a week-long undergraduate botany field course in Tenerife, I got a message from Brian Liddy. He had another batch of Talbot’s images of botanical subjects I might like to look at.

Having looked through the images, Brian asked whether any image struck me as being of particular interest. Personally, it wasn’t a single image that captured my attention but rather the entire collection. I had the impression of looking at an early modern cabinet of botanical curiosities; a collection of objects brought together because they had special interest to the owner. There was even an image of the marine hydrozoan Sertularia, one of the so-called zoophytes and, despite being an animal, regularly found in early modern plant collections.

From the collection of images, I got the sense of someone collecting together all manner of plants of from the garden, glasshouse, wayside and beach. The plants appear to have been selected because of their shapes, sizes and complexities; perhaps with the idea of experimenting with how they would appear as images. The diversity of the subjects makes the images fascinating to interpret. Some were like trying to understand fossilised plant parts, others were like plant fragments that had been treated for anatomical investigation, yet others forced me to refocus continually to appreciate what was being shown. Similar problems occur then trying to identify Victorian nature prints.

During the Canarian field course, students are taught the rudiments of plant morphology using unfamiliar species. Importantly, they’re taught how the various bits of a plant are arranged, the botanical equivalent of the ‘Thigh bone connected to the hip bone’, and that when interpreting structure, you move from the known to the unknown. Therefore, using careful observation, it’s possible to interpret any plant’s structure in terms of its component parts.

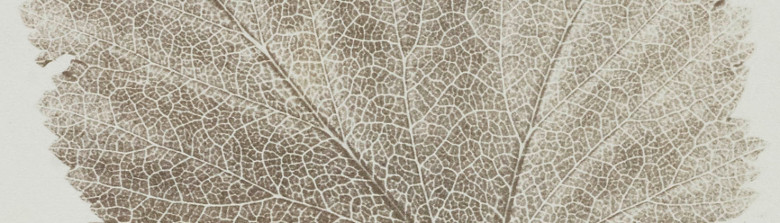

The plants in Talbot’s images, as two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional structures, have been fossilised by light. Like conventional fossils, the details of flat plant parts, such as isolated leaves, are readily captured in this way. Yet how these structures are arranged on the plant, or even whether one is dealing with a complete structure, is lost. Grape and cherry leaves are common among Talbot’s images, often the same leaf. Leaves, or parts of leaves, of members of the carrot family and ferns make striking subjects and appear to have fascinated Talbot.

Detail on many of the leaf images is stunning. There are beautiful details of leaf margins, glands on leaf stalks and venation. In many cases it is possible to know which surface of the leaf, upper or lower, was being photographed. Such details add to the impression of these images as fossil casts, the original object having long since been lost.

Layers of structures, and issues of depth of field, mean naturally three-dimensional objects, such as plant shoots of flowers, present new challenges when they are squashed by light. One tries to focus on the repeated units and work out what is spatially related to what. Being familiar with herbarium specimens (flattened dried plants used to make permanent records of plant diversity) this is a familiar problem. However, with Talbot’s images one is trapped by time; you cannot get to see that detail which is not quite in focus.

Images of some flowering shoots such as that of the flowering current (Ribes sanguinea) are so vivid one feels the desire to turn them over and have a closer look. Yet, like looking through the glass of a museum case, one can never quite get close enough.

Stephen Harris

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • See also Stephen’s guest blog Unraveling the Mysteries of Plants. • WHFT, Photomicrograph of a botanical specimen, air fern (Sertularia), paper negative, date not known, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2030, Schaaf number 1493. • WHFT, Leaf of a plant (carrot family), National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2085/2, Schaaf number 3850. • WHFT, Leaf of a vine (Vitaceae), National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2072/2, Schaaf number 1988. • Detail of Schaaf number 1988 • WHFT, Botanical specimen, flowering shoot of a red currant plant (Ribes-sanguinea), National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1497, Schaaf number 111.

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • See also Stephen’s guest blog Unraveling the Mysteries of Plants. • WHFT, Photomicrograph of a botanical specimen, air fern (Sertularia), paper negative, date not known, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2030, Schaaf number 1493. • WHFT, Leaf of a plant (carrot family), National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2085/2, Schaaf number 3850. • WHFT, Leaf of a vine (Vitaceae), National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2072/2, Schaaf number 1988. • Detail of Schaaf number 1988 • WHFT, Botanical specimen, flowering shoot of a red currant plant (Ribes-sanguinea), National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1497, Schaaf number 111.