Guest post by Brian Liddy

Last week my colleague, Jaanika, asked me if I had any ideas for a new Talbot blog post and suggested writing about Schaaf number 3710 as she had recently added an image making it one of the records on the project website with all its records complete and fully illustrated with an image.

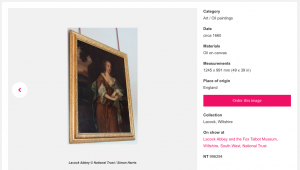

It’s a fascinating photograph of a magnificent oil painting showing a portrait of a woman, with an element of startling informality as the painting is nonchalantly propped against an outdoor wall in the sunshine of the Cloister of Lacock Abbey.

Our conversation turned to the photograph Talbot had taken of the portrait of a woman, indeed, probably of a lady. The problem was, we couldn’t be sure as we didn’t know who she was. To my eye it looked very much like a grand seventeenth century Baroque oil painting on canvas. The canvas is framed, but placed directly on the ground while it rests against the Cloister wall so that it could be photographed by Talbot while the sun shone. I wondered, is that really how to treat a fine Baroque oil painting, never mind a portrait of a lady? We wondered who the woman in the painting might be, and which artist might have been commissioned to paint her. What, if any, was her relationship to Talbot?

Jaanika knows I love trying to put names to the unidentified etchings, engravings, lithographs and occasional oil paintings Talbot turned his camera upon. Together we peered at the computer screen. I said I couldn’t be certain, but thought the painting looked like a Lely or a Van Dyck. Dear reader, try saying that out loud to realise how foolish it sounded. To shore up my sagging reputation I went to that modern wonder, the internet. There we were able to peruse sumptuous portraits of women by both Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) and his near contemporary, Peter Lely (1618-1680). I had to admit they could be hard to tell apart. The pose, the billowing satins and lace, the ringlets and curls, the unsmiling face set against the dark background setting, all endlessly repeated. All the same, yet different. Later, I tried to track down our painting online, but it was elusive. The name of the sitter and attribution of the oil painting remained a mystery, for the time being.

Every time I looked at Talbot’s photograph of the painting I was struck by the sheer audacity Talbot had shown by placing it directly on the ground. If you zoom in on the image using the website’s ‘Image Viewer’ function you will see blades of grass overlapping the painting’s frame! Perhaps Henry instructed staff to remove the painting from its usual hanging place and take it out of doors so that it could photographed. He probably specified the Cloister wall as a good location, both sunny and sheltered from wind for the shoot, but to place the painting directly on the ground seemed risky to say the least, if not a tad disrespectful.

Every time I looked at Talbot’s photograph of the painting I was struck by the sheer audacity Talbot had shown by placing it directly on the ground. If you zoom in on the image using the website’s ‘Image Viewer’ function you will see blades of grass overlapping the painting’s frame! Perhaps Henry instructed staff to remove the painting from its usual hanging place and take it out of doors so that it could photographed. He probably specified the Cloister wall as a good location, both sunny and sheltered from wind for the shoot, but to place the painting directly on the ground seemed risky to say the least, if not a tad disrespectful.

To photograph an original artwork in direct sunlight isn’t as straightforward as you might think. It is a complex task with specific technical issues to overcome, but Talbot clearly felt this painting was important enough to risk taking it outdoors to photograph. Was he considering a photographic reference for a catalogue of his family’s art collection? Or was there something special about this particular painting that motivated him to take the risk? We will probably never know, but only days after Jaanika had added the last image to its record for our ‘Portrait of a Woman’ we had a significant unexpected development. Or, as I prefer to call it, a happy confluence.

Plans had been made some time previously to visit Roger Watson, a valued member of the Talbot Project’s Advisory Board and curator at the Fox Talbot Museum at Lacock Abbey. I haven’t been to Lacock Abbey for many years. My last visit was long before I joined the Talbot Catalogue Raisonné Project. When I met Roger outside the Abbey I kept reminding myself to keep my eyes peeled for items Talbot had photographed that might still be on display at Lacock; and more importantly, might reveal data that would improve some records on the project website. I thought the chances of meeting the woman in our painting were slim to none as most of the major artworks owned by the Talbot family had been donated some years ago to the Ashmolean Museum and the Christ Church Picture Gallery in Oxford. Many of the original artworks that once graced the walls of Lacock Abbey are now on display in Oxford, and there are bound to be even more in storage. So, I didn’t think I would bump into her the day we visited Lacock. Imagine my surprise when Roger lead us into the gallery made famous by Talbot’s photograph of its Latticed Window. There, on the wall not far from the latticed window, was the portrait of the woman Talbot had photographed all those years ago in the Cloister.

Roger fetched a nearby folder which informed us her name was Barbara Slingsby (1602-1658). As a direct descendant of Barbara Slingsby, might that explain Henry’s interest in her? The same folder informed us the artist was not by the great Peter Lely, but only in the style of, or by a lesser un-named follower. So, it seems unlikely he would have photographed the painting for its art historical importance.

A more likely reason Talbot decided to photograph the painting can be found on ‘The Correspondence of William Henry Fox Talbot’ website. There are four letters on the site that cite the name, Slingsby. Barbara is mentioned in her own right, but only in reference to her father, Sir Henry Slingsby of Scriven (1602–1658), or her husband, Sir John Talbot (1630–1714), whom she married in 1660.

Two of these letters are possibly relevant to our portrait painting of a Barbara Slingsby and Talbot’s subsequent photograph of it. Both letters are addressed to Talbot, and both date from 1836. The first is from a historian, the Rev. Daniel Parsons (1811-1887) to inform Talbot of his upcoming publication of the diaries of Barbara’s father, Sir Henry Slingsby of Scriven (1602-1658), for which he was renowned. This news may have made Talbot look at the portrait of Barbara Slingsby in a fresh light and consider it a subject suitable for photography.

The second of Talbot’s letters of 1836 to mention Barbara Slingsby is from his mother, lady Elizabeth Feilding. In that letter, she makes mention to Parsons’s publication of Slingsby’s diaries, and draws her son’s attention to the fact that Talbot owned a portrait painting of Sir Henry Slingsby, “painted when he was in the Tower, just before he was beheaded [for his support of the Royalist cause during the English Civil War] and his daughter married Sir John Talbot.” I need to do some more work before that portrait painting of Sir Henry might come to light along with any photograph Talbot might have taken of it, but Talbot wouldn’t have had to look far before finding the portrait painting of Barbara and then deciding to photograph it.

Photography has come a long way since Talbot’s day, while online resources like the Talbot Catalogue Raisonné Project and the Talbot Correspondence Project are revolutionising access to historic manuscript and art collections the world over, including the one held at Lacock Abbey. Needless to say, the entry for Schaaf number 3710 on the project website will be updated shortly to show the identity of the sitter and painting’s attribution. I’m pleased that at least I was close when I first said, “I think it might be a Lely.”

Brian Liddy

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.ukWHFT, ‘Framed Portrait of Barbara Slingsby by an artist from the School of Peter Lely, propped up in the Cloister at Lacock Abbey’, salted paper print, after 1838, British Library, two copies, Talbot Photo 12(7) and 12(23), Schaaf 3017. • For more information on the original oil painting portrait of Barbara Slingsby at Lacock Abbey, see the National Trust website (number NT996294) and the ArtUK website (also number 996294). • Daniel Parsons to WHFT, 17 March 1836, British Library, London, Doc. No. 3227. • Elisabeth Feilding to WHFT, 20 June 1836, British Library, London, Doc. No. 3306. • Hilary Macartney and Jose Manuel Mantilla (eds.), Copied by the Sun: Talbotype Illustrations to the Annals of the Artists of Spain by William Stirling Maxwell, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, 2016. • See also Dr. Hilary Macartney’s Talbot project blog dedicated to the early photography of works of art for Sir William Stirling Maxwell’s volume, The Annals of the Artists of Spain, 1847.